The year 2014 marks the 75th anniversary of what has long been considered Hollywood’s greatest year: 1939. With the Great Depression in the rear-view mirror, the studio system of filmmaking was in full force. Over seven hundred and fifty films were released that year with eighty million movie tickets sold each week. There was a high public demand for movies of all genres. When the reels of film were finally projected in darkened theatres, audiences were taken back to the Old South and a place called Tara. They travelled by stagecoach with the Ringo Kid through the grandeur of Monument Valley. And they took that unforgettable journey down a Yellow Brick Road that led to an Emerald City.

In 1939, Hollywood itself was an Emerald City—a magical place that was America’s dream factory. This was the Golden Age of the star system when Hollywood marketed larger-than-life movie stars. Names like Garbo and Gable graced the covers of movie magazines and adorned theatre marquees from one coast to the other. But it was a tightly controlled factory. Stars were locked into long-term contracts, and studio scripts had to fall within the moral guidelines of the Production Code in order to be approved. Though the Hollywood operation was run like a business with films made on an assembly line, the studio moguls and the men who made the movies loved what they did. It’s reflected in the fact that so many of these films would go on to become classics. In honor of this glorious era of entertainment, we look back on some of the highlights from a year of unprecedented greatness.

Hollywood’s greatest adventure film comes to the Pickwick on Jan.23!

One of the finest adventure films of all-time premiered in late January of 1939. Gunga Din, directed by George Stevens for RKO, ushered in a year of memorable action films. One of the stars of that film, Cary Grant, also appeared in Only Angels Have Wings. Directed by Howard Hawks, the film told the story of pilots making dangerous flights in South America, and it contained the familiar Hawks theme of friendship among men. Paramount, meanwhile, remade Beau Geste with Gary Cooper, and though it wasn’t a Hollywood film, American audiences saw the British-made The Four Feathers. The majority of heroics, however, came in those thrilling movie serials such as Dick Tracy’s G-Men, Mandrake the Magician, and Daredevils of the Red Circle. Each week audiences flocked to theatres to see the latest installments in these chapter-plays. Science fiction adventures also rocketed across movie screens with the exploits of Buck Rogers, starring Buster Crabbe.

Musicals, however, were guaranteed to attract a wider audience. The end of the decade saw the release of The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle, which reteamed Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. It would be their last RKO musical before they were reunited by MGM in 1948. Busby Berkeley directed Babes in Arms with Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland. But Judy would be remembered for another musical that year—one that would define her career. The Wizard of Oz, directed by Victor Fleming, would become one of the best-loved children’s fantasy films of all time and a family classic that is still going strong today with a recent re-release.

Women flocked to romantic comedies and heard Garbo laugh in Ernst Lubitsch’s Ninotchka. Audiences were laughing with screwball comedies like It’s a Wonderful World and Midnight. Comedy teams like the Marx Brothers were the main attraction in At the Circus while The Three Stooges slapped and hair-pulled their way through shorts like A Ducking They Did Go and We Want Our Mummy. W.C. Fields was still feuding with Charlie McCarthy in You Can’t Cheat an Honest Man, and Bob Hope mixed laughs with chills in the haunted house thriller The Cat and the Canary with Paulette Goddard.

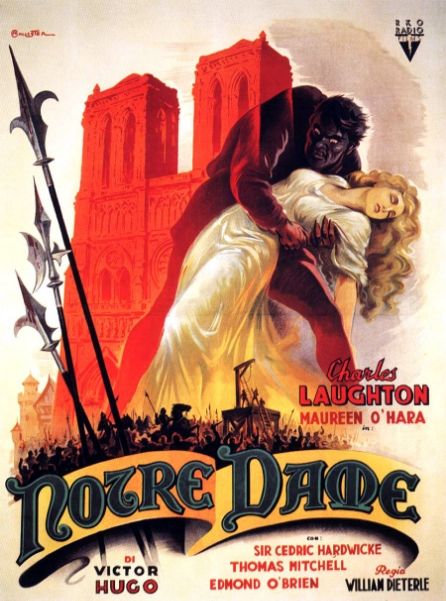

Universal unleashed its horror straight up without the laughs when they kicked off their second wave of classic monster movies. The release of the last great Frankenstein film, Son of Frankenstein, featured Boris Karloff playing the monster one final time. Karloff turned up that same year as the executioner in the quasi-horror Tower of London. RKO, meanwhile, miraculously surpassed the great Lon Chaney silent film The Hunchback of Notre Dame with Charles Laughton in a brilliant performance as the deformed bell-ringer Quasimodo. Maureen O’Hara made her American debut as the gypsy Esmeralda in this remake.

Dramas like Dark Victory with Bette Davis became the very definition of a melodramatic “tear-jerker.” Golden Boy, a story about a violinist who wants to be a prizefighter, made a star out of William Holden. Romantic dramas like Love Affair with Irene Dunne and Charles Boyer and Intermezzo with Ingrid Bergman and Leslie Howard were released to great acclaim. There were also important literary adaptations like John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men and Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Wuthering Heights, besides being a great romance, was also the finest literary adaptation of Emily Bronte. That year Paramount translated Rudyard Kipling to the screen. Ronald Colman, who had earlier been considered for a Civil War epic that David O. Selznick was envisioning, instead starred as the blind artist in The Light That Failed.

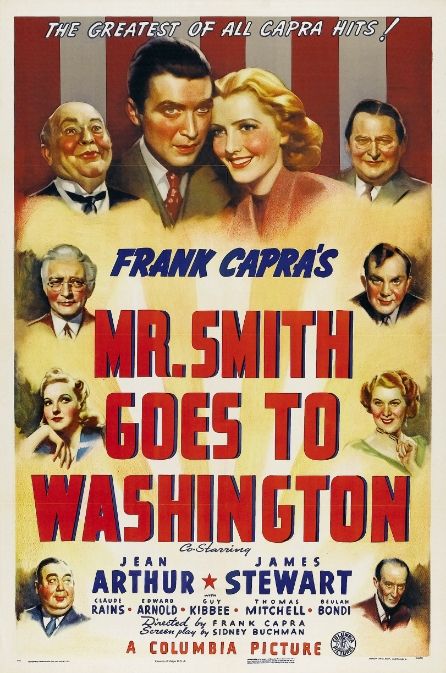

Inner character was at the heart of Frank Capra’s political drama Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. James Stewart’s filibustering senator is one the great performances of 1930s cinema. Goodbye Mr. Chips, in which Robert Donat won an Oscar for Best Actor for his portrayal of an English schoolmaster, was an uplifting film that reflected the very best in life. It also brought Greer Garson to the attention of movie audiences.

A special event is planned for our Mar. 13 screening of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington!

Along with restoring legendary monsters at Universal, Basil Rathbone took up a second career as the immortal Sherlock Holmes in two early installments of the detective series at 20th Century Fox: The Hound of the Baskervilles and The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. In the mystery genre, William Powell and Myrna Loy reunited as Nick and Nora Charles for another crime-solving adventure in Another Thin Man.

The great Chinese detective Charlie Chan was all over the map in 1939. Sidney Toler, who had taken over the role from Warner Oland, was solving crimes in Reno, San Francisco, and Paris. Although these were not prestige pictures, series films were popular at this time. Some of the biggest money-makers were the Andy Hardy films with Mickey Rooney. In 1939 alone, MGM released three films in their series including Andy Hardy Gets Spring Fever. It was also a busy year for Columbia’s Blondie, who brought up a baby, met the boss, and took a vacation all in the same year! Mr. Moto, Chan’s Japanese counterpart played by Peter Lorre, did the same in Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation.

Crime dramas, which had been so popular when the decade began in the pre-Code era, continued to roar on with James Cagney in Each Dawn I Die and The Roaring Twenties. The latter film, which is a homage to the gangster genre, gave Cagney one of his best roles of the 1930s as “big shot” Eddie Bartlett. Confessions of a Nazi Spy, starring Edward G. Robinson, was the first major film to deal with the threat of Nazism. They Made Me a Criminal featured John Garfield and Claude Rains in a film directed by Busby Berkeley—thankfully, with no dance numbers by the Dead End Kids. But in just a few short years, however, the crime drama would evolve into a new darker style that would come to be known as film noir.

James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart traded in their .45s for six-shooters in The Oklahoma Kid. Westerns featured Errol Flynn cleaning up in Dodge City and Tyrone Power robbing banks in Jesse James. Cecil B. DeMille released his railroad epic Union Pacific, and James Stewart starred as the mild-mannered deputy in Destry Rides Again—a film in which Marlene Dietrich memorably sings “See What the Boys in the Back Room Will Have.” The lesser-known Frontier Marshal, essentially a B movie with Randolph Scott as Wyatt Earp, laid the foundation for what would become My Darling Clementine in 1946. One of the most important films, however, was the John Ford classic Stagecoach, an adult Western which elevated the entire genre. It was director John Ford’s first sound Western and it would launch its star, John Wayne, from B-movie obscurity into A-list stardom.

It was a very good year for John Ford who also made Drums Along the Mohawk, a pre-Revolutionary War adventure in color that featured Henry Fonda and Claudette Colbert, and Young Mr. Lincoln—also with Henry Fonda. The latter was a poignant depiction of American folklore chronicling the early years of Abe as a lawyer and featuring a dramatic courtroom scene.

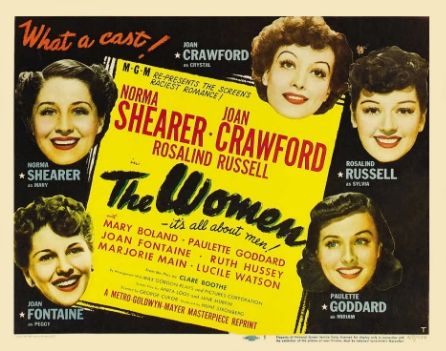

Some of the most popular stars of the era ended the decade on a strong note. Shirley Temple, though slipping in her box office ranking, was still one of the biggest stars at Twentieth Century Fox. She appeared in her first Technicolor film, The Little Princess. Norma Shearer and Joan Crawford (and an all-women cast) starred in George Cukor’s The Women. Bette Davis, who reigned supreme on the Warner Bros. lot, played the empress of Mexico in Juarez and Queen Elizabeth in The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex.

MGM’s two biggest stars: Norma Shearer & Joan Crawford!

Contemporary history was brought to movie screens each week in newsreels like The March of Time. Current events, such as the rise of Adolf Hitler overseas or the 1939 New York World’s Fair at home, were well-documented. In the days before Americans had television sets, the newsreels brought the world to theatre-goers. Besides these newsreels, a movie program also included cartoons. Though he had retired his popular Betty Boop character that year, animation genius Max Fleischer could still rival the best of Walt Disney. His short film Gulliver’s Travels brought an artistic sensibility to animation. Over at the MGM lot, “Peace On Earth” offered a serious anti-war message– even though it was told through the perspective of squirrels. Warner Brothers released many fine “Looney Tunes” in 1939 that featured some of their most popular characters, such as Porky Pig in “Porky’s Movie Mystery” and “Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur.”

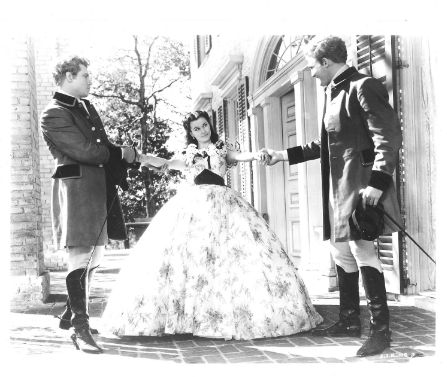

But of all the films released in 1939, one towers above the rest– if only for its sheer size, scope, and Technicolor magnificence. Premiering in mid-December, 1939, it would go on to become a winner of eight Academy Awards including Best Picture. Gone With the Wind remains one of the great achievements of the studio system. Based on a popular bestseller and produced by the legendary David O. Selznick, the story of Scarlett O’Hara and Rhett Butler is now an indelible part of our national consciousness. The characters still resonate, and though their values and notions of chivalry are no longer fashionable, the film continues to fascinate each new generation. Seventy-five years after its release, it remains the most popular movie ever made. It’s a film that has come to symbolize the best of Hollywood– and the best of 1939.

Gone With the Wind will be shown on June 19!

What was it then that made 1939 so special? What alchemy of factors contributed to such a distinct year of grand escapism? Was there anything that separated this year from 1938 or 1940? Soon Hollywood personnel and resources would go to the war effort during World War II, and the postwar years witnessed the gradual decline of the studio system with antitrust legislation and the advent of television. Conditions would never again be as favorable as they were in 1939. For the studio bosses, it was just another year. But time has proven that it was an exceptional year in the studio system. For us now, decades later and in the wake of what’s come after, we can more fully appreciate what the Hollywood dream factory was able to achieve. They gave us films that will last forever.