When: March 13, 2014, 7:30 PM

Where: Pickwick Theatre, Park Ridge, IL

Short: Sons of Liberty (1939) starring Claude Rains

Cosponsored by the Park Ridge Public Library

“Liberty’s too precious a thing to be buried in books… men should hold it up in front of them every single day of their lives and say: ‘I’m free to think and to speak. My ancestors couldn’t. I can. And my children will.”

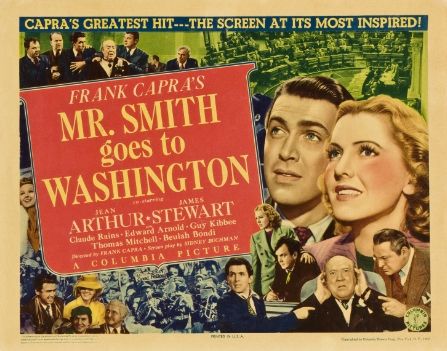

Nominated for eleven Academy Awards, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is one of the standout films from that magical year of 1939. With Frank Capra directing and James Stewart starring, how could there not be magic? Mr. Smith may not have been popular with politicians at the time, but the public embraced it. It’s a film of universal truths that is as relevant today as it was when it was released seventy-five years ago. There is a fundamental decency at its heart, and it is a film with a heart and soul.

Mr. Smith tells the story of a naive junior senator whose ideals clash with the cynicism and corruption around him. Jefferson Smith (James Stewart) is a leader of the Boy Rangers in his home state of Montana. He gets appointed as junior senator only after the governor’s children endorse him over dinner. The governor’s thinking is that Smith will be a malleable choice for the political bosses. Jefferson arrives in Washington, D.C., with a ‘gee, whiz’ wonder at all the buildings and history and lofty words. Senator Paine (Claude Rains), the “silver knight” of the Senate whom Jefferson has always looked up to, takes the young man under his wing. However, it doesn’t take long before Jefferson realizes he’s only there to “decorate a chair.” Paine encourages him to create a bill, which Jefferson does with the help of his secretary, Saunders (Jean Arthur). He wants to have land set aside for a boys camp. The exact location of the proposed camp, however, stirs up a hornet’s nest since it conflicts with the personal interests of the machine and a pork barrel project they are trying to push through. When Jeffereson fails to relent and speaks out, Paine and his bosses smear Jefferson in the hope of getting him expunged from the Senate. With the encouragement of Saunders, Jefferson finds the resolve to make a stand against the machine on the Senate floor.

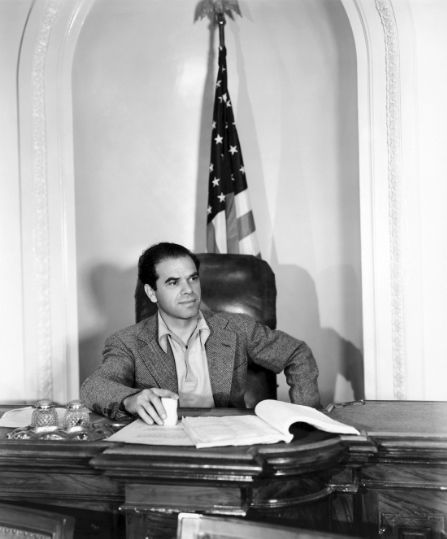

He may not have been President of the Senate, but Frank Capra did serve as head of the Directors Guild of America.

Mr. Smith was based on an original screen story called The Gentleman From Montana by Lewis R. Foster. (Foster would win the film’s only Oscar for Best Original Story.) When the story property was originally brought to Frank Capra’s attention, he instantly recognized themes he could relate to. As with Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, it fit into Capra’s winning formula about the Everyman. In its early stages (Aug. 10, 1938), it was called Mr. Deeds Goes to Washington, a follow-up to the earlier Gary Cooper film. Sidney Buchman was Capra’s writer on the project, taking over for Robert Riskin, who had been Capra’s frequent collaborator. However, it was by no means safe material. Joseph Breen of the Production Code had already rejected two other studios’ attempts to get it made. The story was evidently perceived as an attack on our system of governemnt. According to Mark Vieira’s Majestic Hollywood, Breen would only approve the script if the senators were depicted as “fine, upstanding citizens, who labor long and tirelessly for the best interests of the nation.”

Certainly by today’s standards, Breen’s image of the Senate reads more like science fiction, but even Capra had his doubts early on. When he was in Washington, Capra sat in on a press conference with FDR and began to think of his film in relation to world events. “Nazi panzers had rolled into Austria and Czechoslovakia. England and France were shuddering. Official Washington was in the process of making hard, torturing decisions. And here was I, in the process of making a satire about government officials; a comedy about a callow hayseed who disrupts deliberations with a filibuster. Wasn’t this the most untimely time for me to make a film about Washington?” But as Capra toured the Lincoln Memorial, much like the way Jefferson Smith does in the movie, he realized that what the world needed at that precise moment in history was an affirmation of democratic ideals. “We must make the film if only to hear a boy read Lincoln to his grandpa,” Capra had said after his epiphany. The film shows that America’s form of democracy stands as a model for the world. Our system and our principles are bigger than the little crooks who cast big shadows. By showing the corruption, Capra created a strong contrast that makes Jefferson’s idealism all the more pure.

James Stewart embodied the Everyman the way Gary Cooper had as Longfellow Deeds. Jefferson Smith is one of his finest performances of his career. The film’s most famous scene is Jefferson’s climactic filibuster on the Senate floor. By this point in the story, he’s a much stronger character than the one we had seen earlier in the film; his battles have made him so. Near exhaustion, Jefferson shows the world he’s no political dupe, and the audience is with him every step of the way. In order to sound sufficiently hoarse, like someone who has been speaking for twenty-three hours, Stewart took extreme measures by bringing a doctor to the set. “He dropped dichloride of mercury into my throat,” Stewart said. “Not near my vocal chords, but just in around there. It wasn’t dangerous.” Stewart gives this scene everything he has, culminating with a wonderful speech about “lost causes.” Stewart really hits it out of the park.

It was a star-making role for him. Stewart knew he had been given a great opportunity. If playing second fiddle to Joan Crawford at MGM in The Ice Follies of 1939 seemed like an inauspicious start to 1939 for him, Mr. Smith certainly turned things around. He would appear in another hit that same year when Destry Rides Again premiered in December. Stewart was nominated for Best Actor in Mr. Smith. Though he lost to Robert Donat, he would win the following year for The Philadelphia Story.

Jean Arthur was the ideal Frank Capra actress. She may have been his favorite, having appeared in three of his best films: Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and You Can’t Take It With You (also with James Stewart) being the others. Arthur’s career went back to silent films, but it was in the sound era where she became known for her distinctive, throaty voice. In Mr. Smith, she’s more of a pal and confidante and not just a love interest. Capra’s heroines were strong characters, and Jean Arthur is no exception. She is initally dubious of Smith, in the process revealing her own jaded sensibilities, but his idealism awakens her own spirit. She, in turn, is the one who puts Smith in a position where he can do something about what’s going on in Washington. Without her at his side, he would’ve been on the next train out of town. Arthur’s role as Saunders is a fabulous characterization. One of her best moments is the drunk scene she shares with Thomas Mitchell. Capra had consulted with director Howard Hawks prior to shooting this particular sequence. (Hawks had directed Arthur earlier that year in Only Angels Have Wings.) Jean Arthur may not have been the easiest actress to work with due to her own insecurities, but she could be brilliant on screen.

Claude Rains was nominated for Best Supporting Actor for his portrayal of the once idealistic senator who has since learned to “play ball.” His callousness towards Jefferson in the wake of his betrayal is especially gripping. Capra had wanted someone who could appear senatorial, and Rains certainly looked and acted the part. In Claude Rains: An Actor’s Voice, author David Skal says of Rains, “After working in motion pictures for just a little over five years, he had mastered a subtler technique, acting with his eyes and reining in the declamatory stage techniques on which he had been raised. Never again would he feel the need to back an actress into the camera. Unlike the many mediocre scripts he had elevated with his presence, in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington his talents were placed in the service of a genuinely fine piece of screenwriting.”

Frank Capra was always very careful in selecting his cast. Mr. Smith features one of the greatest supporting casts of character actors you will ever see in one film. Capra had a stock company of actors he would use time and again in his films, but Mr. Smith includes some of the most memorable faces in Hollywood. Today, there aren’t really any character actors– only background performers. But in Mr. Smith, you see that each unique character has a distinct personality and role. This was deliberate on Capra’s part. To him, no part was small. They were all equal. Unlike some other famous directors, Capra loved his actors and it shows by how they are delineated on screen.

Mr. Smith features Guy Kibbee as the jovial but weak-willed governor and Thomas Mitchell as the hard-drinking, cynical reporter. The great Edward Arnold plays the powerful Jim Taylor –not as your typical villain with stock traits, but as someone with a real purpose who is as driven as the hero. Also noteworthy is western star Harry Carey as the President of the Senate. Capra had wanted “a strong American face” for the role and remembered Carey’s kindness and generosity from twenty years before when Capra was working as an extra on a John Ford western. In Mr. Smith, Capra repaid that kindness. Though Carey only has about 20 lines in the film, audiences remember his reactions to Jefferson; they stand in for those of the audience. He is us, and so his presence in the film serves a dual role other than just officiating. Capra even gives him the final shot of the movie.

Capra was making this film for penny-pinching Harry Cohn at Columbia, who wanted less takes of scenes printed. To work around this dictum, Capra would simply let the camera roll continuously in order to record the best of several takes shot together. He discovered that more times than not, the second take was almost always better than the first. His cameraman was Joseph Walker, who was a mainstay in Capra’s productions. The stellar work of cinematographers like Walker should make modern audiences appreciate the value and quality of black and white photography. The scenes at the Lincoln Memorial are exceptionally well-lit. One of the most striking scenes in the film is the one in which Saunders finds Jefferson in tears and in the shadows.

One unsung hero in the making of Mr. Smith is Slavko Vorkapich, who handled the montage effects. To capture the history of Washington, D.C., in just a few moments of screen time (and to make it seem fresh) is no easy task, but the imagery is exciting. Vorkapich was known mostly as a montage editor. Some of his best work includes the special effects in the opening sequence of Crime Without Passion (1934). The stunning visuals in this independently-made film feature “the Furies” flying over a city of lust and murder.

It does appear that additional footage was shot for Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. I found this production still (below) from the film which depicts Guy Kibbee’s Governor Hopper visiting Jefferson early in the film. When you watch the released version, the governor arrives and enters the home filled with kids. Almost immediately Beulah Bondi (playing Jeff’s mother) closes the door. The film then jumps to the “star-spangeled” reception where we see Jefferson Smith for the first time, appearing out of place at a banquet table. It never really felt like that was his first appearance. If Capra had cut out the earlier scene due to time constraints, it most likely depicted Smith at ease in his natural element as a Boy Ranger leader. This would’ve been a nice contrast to the following scene at the banquet hall. There was also an alternate ending to the film that was removed after its preview. Originally, Jefferson and Saunders return to his hometown in an extended denouement. (In the film’s trailer, you can see them riding in a parade.)

The musical score was by Dimitri Tiomkin, who had scored Capra’s Lost Horizon. Capra told him he wanted to hear America in the score and Tiomkin delivered. Throughout the film you hear many musical motifs right out of the American folk songbook– songs like “Yankee Doodle” and “My Country ‘Tis of Thee.” The film evokes that pioneer spirit. Just listen to the scene where Saunders finds a disillusioned Smith at the Lincoln Memorial, ready to leave town after being tarred and feathered. That’s all Americana in the background. The musicality of the film is often overlooked with all the standout performances, but it’s another aspect that makes the film work.

Writer Sidney Buchman didn’t think the ending worked. He believed Capra oversimplified things, citing the melodramatics of Senator Paine trying to commit suicide. But everything works within the context of the film. The 1939 audience wanted to see Paine get what was coming to him. In real life, I don’t think any politicians would make an admission of guilt on the senate floor, but Jefferson Smith stirred Paine’s conscience. The plot points might not be “realistic” but the film’s convictions are genuine.

The film depicts the power of the media and its influence, which is just as relevant in 2014; however, there is a noted difference in how they operate then and now. In Mr. Smith, the press is depicted as the only honest body in Washington– the only ones who really know the truth because they don’t have to worry about getting voted out of office. Compare that to today when the press is run by corporations with a slanted point of view. Mr. Smith shows how things should be. Maybe viewers will think the film’s perspective is as naive as Jefferson Smith’s when he first enters the Capitol, but it’s simply not a cynical film. It believes in moral heroes.

As previously mentioned, many in Congress were not happy with the film when they saw it. One senator called it a “grotesque distortion” of Congressional proceedings, saying that no member would seriously be taking their cues from someone up in the gallery. The Washington Press Corps was equally offended at being portrayed as a bunch of drinkers. U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain Joe Kennedy thought the film would hurt America’s image abroad, but like the theme of the movie, Capra responded back using the voice of the people– hitting back at Kennedy’s charges the way the Boy Rangers do to crooked Taylor with their circulars. The people spoke, and Mr. Smith became a hit with audiences and critics. The film didn’t damage America’s image abroard– certainly not in the countries being overrun by Nazis. For moviegoers in France, for instance, who watched James Stewart’s dramatic speech near the end, they were hearing things in a movie theatre that they would not hear again for a long time. Mr. Smith was a celebration of freedom made at a time when the storm clouds of war were threatening the world.

Beyond its value in the face of World War II, Mr. Smith contains universal themes that are just as relevant today. Its populist appeal still strikes a chord in the modern viewer. There really would be no point in remaking it. But this is a Hollywood now that turns Adam Sandler into the new Longfellow Deeds, so you never know. Hollywood just might get that urge not to entertain, as they used to do, but to push an agenda into a piece of political propaganda. But in Mr. Smith, the characters are not even identified as either Democrat or Republican. (Though the astute viewer can figure this out based on where the characters are sitting in the Senate.)

In preparing this event, I wrote to two former Presidents– one on each side of the aisle. I had this notion that Frank Capra’s film deserved a presidential acknowledgement because it mirrors the best of the American spirit. It’s so much a part of not only our cinema heritage but our cultural heritage as well, representing the best of what we were and what we can be again. (I didn’t get a direct response, but at least the Office of President George W. Bush was kind enough to acknowledge our film program, for which we are grateful.) But you wonder how many politicians have actually seen this film. How many are truly inspired the way Jefferson Smith was? Few, if any. The underlying message should appeal to the hopes of both parties; the conservative Tea Party, for example, has embraced the film. No doubt the grassroots efforts of the Boy Rangers to get the word out with the odds stacked against them find resonance. The battle for public opinion is just as timely today.

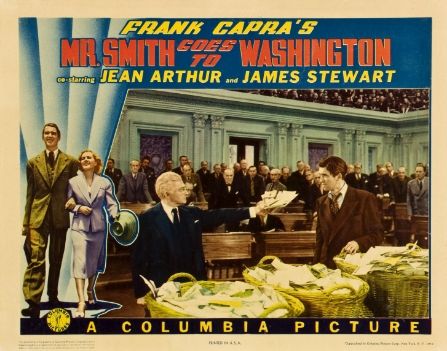

The U.S. Senate floor recreated in Hollywood…

The fact is people have grown weary of politics, and in this context, a film like Mr. Smith is all the more important for our community. Certainly what is depicted in Mr. Smith has been comically exaggerated in our own reality. You have a system of gridlock where politicians endlessly talk in cliches when they’re not running for re-election, shutting down the government, or being formally charged with corruption. We long for a Jefferson Smith– someone to speak in the voice of the people and who can apply the moral (behind Capra’s vision) to real life. Here is a character who believes in those words carved in marble on the monuments– someone who is filled with history and an appreciation for the nation’s system of government. That ideal is put to the test against the realities of politics. In Smith, we have a 1939 incarnation of Abraham Lincoln– someone who represents America’s promise. These associations were deliberate on Capra’s part.

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is a film about how one man can make a difference. It was a recurring theme in the best of Frank Capra’s work. It’s a theme that is universal and will remain so a thousand years from now. We don’t know how long Mr. Smith will be a part of our national consciousness. Films I took for granted that people had seen had not been. But Mr. Smith is a movie every family should experience. Mr. Smith reminds us of the importance of our liberties and freedoms that we sometimes take for granted and what life would be like without them. It inspires us the way Jefferson himself was inspired looking at that Capitol building and believing it could come to life. In these dark days of cynicism and apathy, Mr. Smith shines like a beacon that can’t be extinguished.