“If you believe in your dreams, your dreams will come to life.” ~ Colleen Moore

On May 7, 2015, the Pickwick Theatre Classic Film Series will conclude its second season with a screening of Why Be Good? (1929) starring Colleen Moore. The event, which has received national coverage through Turner Classic Movies, will have several attractions including a visit from Alice Hargrave, Colleen’s granddaughter. Today, Colleen is probably better-known to the general public for her “Fairy Castle,” which remains one of the most popular exhibits at the Museum of Science & Industry in Chicago. In her day, though, Colleen was one of the biggest stars in Hollywood. She came to symbolize the spirit of the Jazz Age and was the first successful “flapper” in the movies. But that was over ninety years ago. Many will be asking, “Who was Colleen Moore?”

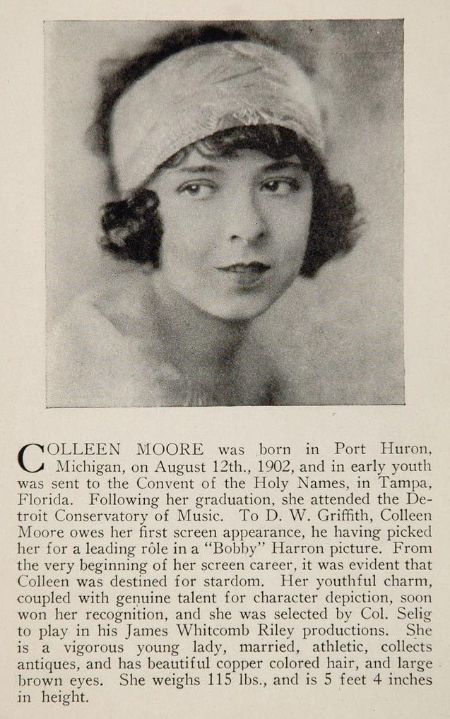

Colleen Moore was born Kathleen Morrison on August 19, 1899, in Port Huron, Michigan. She was the only daughter of Charles and Agnes Morrison. Due to Charles’ various business ventures, the family was often on the move, living in several homes in Michigan. They sometimes summered in Chicago where Kathleen had a favorite aunt. It was during one visit to Chicago around the age of five when Kathleen saw a theatre production of Peter Pan. It would make a lasting impression on her because for the first time she understood what it was like to captivate an audience.

By 1908 the family had relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, before settling in Tampa, Florida, three years later. Her father had a machinery business there. As a young girl in Tampa, she saw many movies and was a fan of the popular stars of the day, especially Lillian Gish. Kathleen always intended not only to be an actress, but to be a star. Her ticket to Hollywood came in 1917 in the form of what she termed a “payoff.” Her influential uncle, Walter Howey, managing editor of the Chicago Examiner, had been instrumental in getting D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation past the Chicago censors. As a return favor to Howey, Griffith invited Kathleen to Hollywood. With her grandmother and mother in tow, Kathleen– renamed “Colleen Moore” by her uncle– took the California Limited west.

Before coming to Hollywood, Kathleen had a screen test done at the Essanay Studio in Chicago to see how her eyes registered onscreen. Though these were the days before color film when such details would not have been picked up by the camera, Colleen had a unique physical feature called heterochromia: she had one brown eye and one blue eye. She passed the test. (In later years, Moore claimed to have been a background extra in some films made at Essanay. It is possible that this could’ve happened earlier during her frequent stays in Chicago with her Aunt Lib.)

These were the early days when Hollywood was not far removed from the citrus groves that had dominated the landscape. In fact, most of the land was still rural. Only a few years before, Cecil B. DeMille had shot the first movie ever filmed in Hollywood, The Squaw Man. One of the first movie sites Colleen saw was the set of Intolerance, which was still standing. At Griffith’s Triangle-Fine Arts studio, she met members of his stock company and was immediately cast in a film. Colleen cites a movie called Bad Boy (1917) as her first screen credit.

In those days, many girls were cast for type. Young actresses who photographed well often played “adults” even though they themselves were only teenagers. During this time, Colleen learned the rudiments of acting– namely, which angles were to her best advantage and, more importantly, to never get upstaged by another actor. After appearing in some program films for Griffith, Colleen worked at other studios including Selig and Ince Studio. She learned comic timing on-screen while working for the Christie Film Company. In these early years she appeared with cowboy star Tom Mix, whom she greatly admired. In her estimation, he was a real cowboy hero, and the West was the romantic place in the world.

Despite working at Griffith’s studio, Colleen’s only opportunity to appear in one of his major productions came with a small role in his World War I epic Hearts of the World (1918). Unfortunately, her relatively minor part was left on the cutting room floor. Gradually, her career as an ingenue was boosted towards stardom. She found steady work with directors like Mickey Neilan (Dinty, 1920) and King Vidor (The Sky Pilot, 1921). It was Neilan who introduced Colleen to the man who would become her husband, John McCormick. A press agent at the time, McCormick would later become production head for First National Pictures, which was then a subsidiary of Warner Brothers. When First National went into the business of producing films, McCormick made sure Colleen Moore would be one of the first stars they signed. She appeared in a couple films as the lead, but the upper brass at the studio felt she could not carry a film on her own. It seemed to her as though she would remain a “featured player” but never a star.

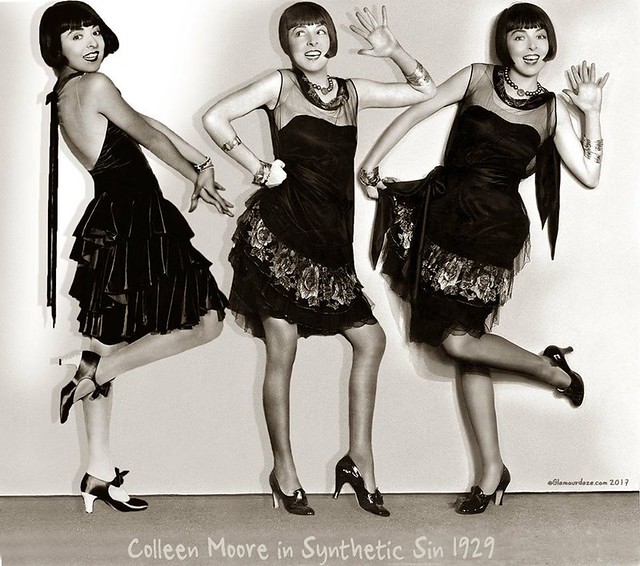

The turning point in her career came with a story called Flaming Youth (1923), which had been a scandalous, best-selling novel about “neckers, petters, white kisses, red kisses, pleasure mad daughters, and sensation craving mothers.” Colleen wanted the role of wild daughter Patricia Frentiss badly, so with the help of her mother (who had since joined her in California), she overhauled her screen image. Gone were the long curls. Afterall, she knew she wouldn’t be another Mary Pickford. The “sweet young thing I was not.” Her mother cut her hair into a Dutch bob. Colleen got the role in Flaming Youth, and with it, she created a new screen type– the emancipated young girl who defies convention. She defined the Roaring Twenties with her bobbed hair, short skirts and rebellious nature. It was Colleen Moore who put this new American type in vogue. As F. Scott Fitzgerald later wrote, “I was the spark that lit up Flaming Youth, Colleen Moore was the torch. What little things we are to have caused all that trouble.”

Colleen Moore had a wonderfully expressive face that enlivened the movie frame. She was at her best as a comedienne, but she could also handle serious drama as she demonstrated with her performance as Selina in So Big (1924)– her favorite role. Though Barbara Stanwyck would later appear in the remake, author Edna Ferber always believed it was Colleen Moore who did the part justice.

In Silent Star (1968), Colleen’s autobiography, she recalls the early days of Hollywood– the stars she knew and the scandals that were talked about. She also tells of her connection to someone who would go on to become a major star in the 1930s and 1940s: “One day, while I was making a film called Her Wild Oat, I saw among the extras the most beautiful little girl I had ever seen. I suggested we make a test of her. When I saw the test the next day with the studio brass, I was elated. She was even better than her promise. To my shock, the bosses, even John, said, ‘But her teeth stick out in front.’ I said, ‘For heaven’s sake, she’s only fourteen years old. Haven’t you ever heard about braces?’ So they signed her to a contract and sent her to a dentist. Convinced now they had another Corinne Griffith on their hands, the bosses wanted to change her name to something more romantic than her own name Gretchen Young. So I named her– after the most beautiful doll I had ever had, Loretta.”

Colleen’s popularity grew as the decade wore on. By 1926, she was the #1 box office attraction according to an exhibitor’s poll. She was making $12,500 a week. In 1928, she appeared in one of her most famous and prestigious films, Lilac Time, which co-starred a relative newcomer named Gary Cooper. Lilac Time, a drama about World War I pilots, was a huge hit. It was also the first film screened at a theatre newly built in Park Ridge, Illinois, called the Pickwick Theatre.

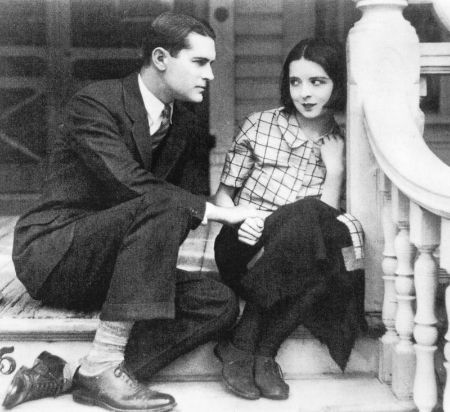

Colleen with Neil Hamilton in Why Be Good?, a great showcase of Art Deco set design.

By the late 1920s, sound was changing the face of Hollywood. New technology enabled sound to be recorded on disc. It was then played in sync with the movie as it was being projected. Dialogue and sound effects were being heard for the first time in theatres. But before Colleen made her first all-out “talkie,” she appeared in a Jazz Age comedy called Why Be Good? (1929) directed by William Seiter (who would go on to direct Laurel & Hardy’s best feature comedy, The Sons of the Desert). Similar to her earlier roles, Colleen played a character who was a carefree spirit who dared to ask the tantalizing question, “Why be good when it’s so much more thrilling to be bad?” However, what separated Colleen Moore from others like Clara Bow– her box office competition– was that audiences knew Colleen was a good girl at heart. Not only did Why Be Good? present the 1920s flapper in all her glory, but it also showcased a modern architectural style known as Art Deco. Why Be Good? rivals the modern-looking set designs of other great Art Deco films of the era including MGM’s Our Dancing Daughters (1928) starring Joan Crawford.

Though Colleen found great success on movie screens, personal happiness eluded her. Her troubled marriage to John McCormick was exhausting and took its toll on her. McCormick was an alcoholic who twice tried to kill her while drunk. His bizarre, often erratic behavior eventually led to divorce in 1930. But in the late 1920s, Colleen found a means of escape–a happiness away from home. In 1928, she started creating one of the most enduring aspects of her legacy. A lifelong collector of dollhouses, Colleen set out to build the ultimate “fairy castle.” Though Colleen had been in awe of (William Randolph) Hearst Castle during her many visits to the San Simeon retreat, the idea for the dollhouse came not from the publishing tycoon but from her own father who inspired it. Nevertheless, Colleen insisted her castle would have “the same feeling as San Simeon.”

Her father had conceived it, and with the help of architect Horace Jackson, who designed the floorplan, and decorator Harold Grieve– as well as many others who worked at First National– Colleen’s dream fairy castle became a reality. Cast in aluminum and made up of 200 interlocking parts, the castle was roughly nine feet square (one inch to the foot) with its tallest tower 12 feet high. It was made up of eleven rooms filled with nearly 1,500 objects including miniature books, furniture, and antiques. Every room was inspired by classic fairy tales and legends. Every room told a story. The castle even had its own plumbing and electrical systems. What started out as a hobby became her escape. With the help of friends, the castle grew over the years into a lasting work of art. She finished the castle in 1935. This fantasy world would become more than just a large dollhouse. It not only reflected her persona, but it became a museum unto itself– a repository of art, history, and culture.

Colleen’s Fairy Castle at the Museum of Science & Industry, Chicago. (photo courtesy of MSI)

By the mid-1930s, Colleen’s career would be finished as well. She had made a handful of sound films, but her favorite was always The Power and the Glory (1933) with Spencer Tracy. She felt Tracy was the finest actor she had ever worked with. It was a dramatic role for her, and though it received critical praise, the public did not accept her in this type of role. Colleen had no desire to return to what she had once been in the 1920s and so bowed out of Hollywood.

After a short-lived marriage to a good friend of hers, Albert Parker Scott, Colleen finally found marital happiness when she met Chicago stockbroker Homer Hargrave in 1936. Homer was a widower with two children whom Colleen accepted as her own: Judy and Homer, Jr. She was introduced to Homer while she was on tour with her dollhouse to raise money for crippled children. At many city department stores across the nation, her castle became a great attraction. The tour eventually raised over $600,000. Colleen married Homer in 1937. As a pre-honeymoon trip, Homer took her to Riverview Amusement Park.

Colleen considered The Power and the Glory her finest film.

It was during her years away from Hollywood that Colleen developed a greater sense of community. She became what she called a “private” person– that is, a person from the private sector outside of Hollywood. Over the years, Colleen remained active. Having wisely invested her money, she wrote a book called, How Women Can Make Money in the Stock Market (1969). She also helped found the first Chicago International Film Festival. Colleen remained married to Homer until his death in 1964. In 1983, she married a building contractor, Paul Maginot. They would remain together until her death from cancer in 1988.

Colleen Moore didn’t have the erotic charge of Louise Brooks, another flapper icon who has attained cult status, but Colleen was a bigger star in America than Brooks ever was, and she defined the look of the flapper well before Brooks. Colleen dosen’t have the name recognition of Clara Bow, the “It” girl whose affairs and controversial behavior off-screen added to the public’s fascination with her. Colleen, by contrast, led a scandal-free life, proving that not every star in Hollywood was without values. Though Colleen was the prototypical Jazz Age heroine who broke from conformity in order to have fun, her characters were never decadent. In fact, she always kept her old-fashioned decency in the end. Her sin was of the synthetic variety.

Colleen with Lloyd Hughes in Ella Cinders, 1926.

Due to her immense popularity in the 1920s, Colleen was a trend-setter who shaped fashions and hairstyles. But beyond the iconic look, she was an actress of great energy, humor, and heart. Most importantly, Colleen was a wonderful person in real life who was motivated by charity and who gave back to the community.

With so many of her films out of circulation– only Why Be Good? is commercially available now while some titles exist in lesser-quality dvds– it might seem a daunting task to generate a demand for Colleen Moore. Added to this is the fact that many of her films are simply lost. (Due to the carelessness of a staffer at the Museum of Modern Art, some of her films deteriorated beyond repair.) But there is hope that Colleen will be more than a mere footnote in film history books. Some of her films are surfacing while others exist partially. More recently, the Vitaphone Project has restored and released her last two silent films (with the original Vitaphone sound): Synthetic Sin and, of course, Why Be Good? With the goal of continued preservation as well as proper exposure of those films that do exist, Colleen Moore can again be recognized as one of the great stars in the Age of Silence. We hope that our screening, along with others across the country, will lead to what Alice Hargrave has called a new wave of Colleen Moore interest.

For more about Colleen Moore, please visit the website: https://sites.google.com/site/colleenmooresite/

~M.C.H.

“Here was a chance for a girl who had straight hair, who was not buxom and not a great beauty. A new type was born– the American girl.” ~ Colleen Moore