A near-capacity crowd came out for our World War II event at the library.

The following is a transcript from our introduction of Twelve O’Clock High on August 6, 2015. We had 82 patrons attend this special event at the Park Ridge Public Library. We were honored to have two World War II veterans with us. In addition, a 17-minute slideshow accompanied the presentation. We have dedicated this screening to George E. Schatz, who passed away five days before the event.

Our screening tonight is more than a tribute to a great film, it’s a salute to all those Americans who served during the Second World War. To honor The Spirit of ’45—the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II— and to keep the history alive, we are screening Twelve O’Clock High. Released four years after the war had ended, the film deals with the daylight bombing missions of the Eighth Air Force, which was stationed in England. Though we are unable to honor all the branches of the military, Twelve O’Clock High reflects the stress and danger that all servicemen face in times of conflict; it shows the human cost of war.

Twelve O’Clock High has an integrity that is on every page of its outstanding screenplay. It transcends the macho clichés of the genre by presenting a picture of war rooted in fact. It accurately reflects what the pilots of the Eighth Air Force had to suffer. Those who have served our country recognize more keenly the realities and truths depicted in Twelve O’Clock High. Like the flashback that opens the film, I’d like to reflect back and explain how I discovered this movie and why I selected it.

About fourteen years ago I was planning a film screening of Frank Capra’s Lost Horizon at the LaSalle Theatre in Chicago. Ronald Colman, the film’s star, has always been my favorite actor, so I contacted a gentleman from Highland Park who I knew was a Colman scholar. In fact, he had created a group with other historians called the Ronald Colman Appreciation Society. His name is George E. Schatz and he provided me with a written introduction to my screening. I got to know George, and when I visited him at his home he had a museum in honor of Colman and Lost Horizon— from theatrical posters to movie still albums the size of Chicago phonebooks. It was a passion of his that went back to the film’s release in 1937.

But there was another facet of George Schatz that I learned about. He was a veteran of World War II. He had been a bombardier on a B-17 Flying Fortress, having flown 32 missions as part of the 600th Squadron. There were various artifacts from his war years on display, including an apparatus that was part of a bombsight from his plane. There it was in his basement, over a half century since the last bomb had dropped– a silent reminder of the harrowing experiences he had survived. George recorded some of those experiences for the 398th Bomb Group Memorial Association. It was entitled, “The Ken Elwood Crew: A Bombardier Remembers…” Ken Elwood was the pilot of George’s B-17. I’d like to read an excerpt from this in which George talks about Ken’s outstanding skills. The full text can be found as part of the Veterans History at www.398th.org:

George E. Schatz, front row, second from left.

“In February of 1944 while on a practice bombing mission in South Dakota, a fire in the bomb bay door motor had me and the engineer trying to turn the doors back up with the manual handle, and then we lost each of our four engines on our B-17 in turn from carburetor icing. By this time we were too low to jump and our whole crew went into our practiced toboggan mode in William Hanna’s radio room.

“Meanwhile Ken Elwood and co-pilot John Hutchison attempted to make a ‘wheels up’ landing on the belly of our B-17 ‘Flying Fortress.’ Elwood made such a perfect, smooth landing on a snow-covered wheat field that we neither bounced nor even suffered a hangnail. After our crew quickly exited the plane, saw that there was no fire, two men trudged towards a farmhouse to phone. It was my duty to go back into the eerie quiet hollows of our slumbering aluminum giant and rescue the then ‘top secret’ Norden Bombsight. The four ambulances sent out by the base to ‘rescue’ us proved to be a more harrowing trip than Elwood’s landing but our entire crew was then treated by the Colonel to “The best steaks in South Dakota.’ Elwood’s belly landing had been so gentle, that after fixing the props, and lifting it, Col. Hunter flew that B-17 out of the wheat field on a metal-grid runway.”

There were many dangerous missions for George and his crew. He once told me that on his second mission over Berlin, “when fighters hit the ‘composite’ Group in front of us (which partially contained B-17s from our own 398th Bomb Group) and parts of bodies and planes ‘floated’ past us, my navigator and I wondered why we weren’t ‘sickened’ (as our pilot was) and we decided it was so awful that our ‘minds’ could only grasp it as somehow ‘unreal’– like a movie!”

On another occasion over Merseburg, Germany, flak came through the nose of the plane and knocked Plexiglas into George’s left eye. Their last mission, on August 8, 1944, took them over the English Channel in a low altitude run in support of General Montgomery’s men. The group bombardiers had to distinguish between the Allied lines and the Nazis, so there was no room for error. Flak hit the windshield and flew into Elwood’s eyes. Then later on the same mission, there was a near collision upon landing with another plane coming in underneath them. They survived that last run, and Ken Elwood recovered, but the celebration was short-lived.

George writes, “The fourth bright, shining morning after our crew’s final mission, I was hanging some freshly washed socks and handkerchiefs out to dry on a fence railing near our hut, happy and relaxed as a clam. Then some officer walked down towards us, probably from our 398th’s Headquarters, and seeing me, came over and told me that the crew that had taken over our plane, plane #191, were all killed when it exploded while it was circling around on its climb up to assembly over England! I have an old small Kodak photo of Charlie Searl and Leo Walsh on which I had written on the back, in pencil: ‘Played ball with these two boys yesterday; today they are dead! Lost over England in our #191 plane.’ There were no survivors of that Searl Crew on that morning of August 12, 1944.”

Had the Ken Elwood crew been pro-rated to fly 33 missions instead of 32, George Schatz’s life would have been cut short like so many of the Bomber Boys who had perished. When I visited George, I remembered seeing amidst his collection various items from Twelve O’Clock High including original posters. The book and film had made an impression on him. To George, it was the “truest” Air Force film.

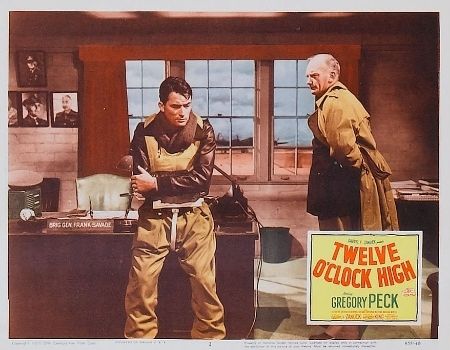

Twelve O’Clock High opens in the years after the war, with an American officer visiting an abandoned airfield in the English countryside. The officer is played by Dean Jagger, who would win an Academy Award for his performance as Major Harvey Stovall. His story leads into a flashback to 1942. These are the early days of the war when America and England were suffering heavy losses. The story follows a “hard luck” Bomber Group in the Army’s Eighth Air Force. They are responsible for the daylight precision bombing missions over Nazi Germany. However, the pilots suffer from poor morale as a result of increasing casualties. The men are led by Col. Davenport, as portrayed by Gary Merrill. He has become too protective of his men, and as a result of this over-identification, he can no longer effectively lead them. He is replaced by General Savage, played by Gregory Peck. Savage brings leadership rooted in discipline. The least competent men he re-assigns to a unit known as the “Leper Colony,” headed by Col. Ben Gately (Hugh Marlowe), who had previously shirked his duties. Savage must turn the group around and change their defeatist attitude. Ultimately, that change must come from within the men.

Twelve O’Clock High is based on a 1948 novel by Beirne Lay, Jr. and Sy Bartlett, both of whom wrote the film’s screenplay as well. The two were combat men who had served in the U.S. Army Air Force during World War 2. The film is based on their experiences. Lay had been an intelligence officer in the 8th Bomber Command. Bartlett had worked in Hollywood at 20th Century Fox before Lay brought him into the intelligence unit. Later, Bartlett would pitch Lay on his story idea about the 306th Bomb Group. To sell Lay on the idea, Bartlett said, “You know, when the war ends, people are going to forget what happened here. They won’t care anymore. To prevent that from happening, you and I are going to write a novel about the Air Corps.” Though the names in the book are fictional, the characters they created are based on real people they had known.

Frank Savage, for instance, is based of the life of General Frank A. Armstrong, a legendary figure in the history of the Eighth Air Force. During the war, Armstrong took over the command of the 97th Bomb Group and led the first daylight bombing raid over Europe. He later reorganized the 306th Bomb Group—rebuilding its discipline and training– and then leading their first mission to bomb Germany. For the novel, the authors created the 918th Group by simply multiplying 306 by 3.

“Consider yourselves already dead. Once you accept that idea, it won’t be so tough.” ~ Gregory Peck as General Savage, Twelve O’Clock High (1949)

Gregory Peck, who was nominated for Best Actor for his performance, thoughtfully conveys to the audience the burden of commanding men. Savage must exert his authority, but it is never done to assert a self-importance. The fundamental drive is his commitment to the men. The task is to instill flying discipline and group integrity. New leaders will emerge as a result. In fact, Twelve O’Clock High is often used as an example of the principles of leadership, both in the military and corporate worlds. Gregory Peck’s character shows what it takes to be a leader with a clear sense of purpose and methodology. The film has been screened from Air Forces bases to executive management classes.

During the war there were many films that simply offered action and flag-waving heroics. These films had more propagandistic objectives, but after the war, filmmakers were able to explore the subject on a deeper level. Twelve O’Clock High is about the psychology of war. The emphasis is on the human drama rather than the mechanics of warfare. The theme that runs throughout is the mental breakdown. Everything leads to that. Though no U.S. general suffered the kind of paralysis seen in the film, the writers of Twelve O’Clock High merely extrapolated on the idea and wrote about something that could have happened given the circumstances.

Films made during and immediately after the war radiate an authenticity that contemporary war films lack; they carry with them the voice of experience. Filmmakers back then did not play soldier. They lived it. There is a mistaken perception today that if somehow a film presents a hyper-sense of reality—a depiction of combat complete with hand-held cameras and graphic make-up effects—it is somehow truer to the horror of war. There are no depictions of men being blown up in front of our eyes in Twelve O’Clock High, yet the film has an honesty few films today attain. The great war directors like Ford, Capra, Huston, Wyler, and others did not have to shock an audience or manipulate them with sentiment.

Twelve O’Clock High is a film told with authority by those who knew that time in history. It is true to the situations it depicts. This has been recognized by veterans who have served and who understand the trials. Many of the people connected to Twelve O’Clock High had been involved in the war themselves. In addition to the screenwriters, director Henry King, who was already in his fifties when the war began, was the deputy commander of the Civil Air Patrol having attained the rank of captain. He had years of flying experience in the private sector. Before the war, King had taught movie legend Tyrone Power how to fly. Twelve O’Clock High also featured an actor with real-life aircrew experience, Robert Patten, who plays Lt. Bishop.

The film was personally supervised by Daryl F. Zanuck who took over as producer. Having purchased the rights to the story for $100,000, he helped develop the screenplay. One of Zanuck’s contributions included removing an unnecessary romantic element from the novel. Twelve O’Clock High was originally planned for Technicolor, but instead was shot in black and white so as to incorporate actual war footage of planes in distress taken by both the Allies and the Luftwaffe. This footage was seamlessly integrated into the film by editor Barbara McLean.

Twelve O’Clock High opens with one of the most memorable moments in the movie–that of a B-17 crash landing. This scene was performed by ace stunt pilot Paul Mantz. He had to guide a 38,000 pound plane 1200 feet while traveling at 110 mph. This was reportedly the only time a B-17 took off and was flown with only one crewman onboard. The spectacular sequence recalls the landing George Schatz and his crew experienced in the wheat fields of South Dakota. However, the incident in the film is actually inspired by the heroics of real-life Medal of Honor recipients such as John Morgan, a B-17 flight officer who, during a 1943 mission over Germany, had to fight off a disoriented and severely injured pilot in order to bring the plane in safely. In the film, this character is portrayed by the fictional Lt. Bishop. However, the actual landing of the B-17, as depicted in the film, recalls the heroics of other real-life airmen such as Chicago native Edward S. Michael. In April of 1944 Michael and the members of the 364th Bomb Squadron were flying a mission over Germany when their B-17 was singled out by enemy fire. The plane was heavily damaged and caught on fire. Michael’s official Medal of Honor citation reads in part:

“With a full load of incendiaries in the bomb bay and a considerable gas load in the tanks, the danger of fire enveloping the plane and the tanks exploding seemed imminent. When the emergency release lever failed to function, 1st Lt. Michael at once gave the order to bail out and 7 of the crew left the plane. Seeing the bombardier firing the navigator’s gun at the enemy planes, 1st Lt. Michael ordered him to bail out as the plane was liable to explode any minute. When the bombardier looked for his parachute he found that it had been riddled with 20mm. fragments and was useless. 1st Lt. Michael, seeing the ruined parachute, realized that if the plane was abandoned the bombardier would perish and decided that the only chance would be a crash landing. Completely disregarding his own painful and profusely bleeding wounds, but thinking only of the safety of the remaining crewmembers, he gallantly evaded the enemy, using violent evasive action despite the battered condition of his plane. After the plane had been under sustained enemy attack for fully 45 minutes, 1st Lt. Michael finally lost the persistent fighters in a cloud bank. Upon emerging, an accurate barrage of flak caused him to come down to treetop level where flak towers poured a continuous rain of fire on the plane. He continued into France, realizing that at any moment a crash landing might have to be attempted, but trying to get as far as possible to increase the escape possibilities if a safe landing could be achieved. 1st Lt. Michael flew the plane until he became exhausted from the loss of blood, which had formed on the floor in pools, and he lost consciousness. The copilot succeeded in reaching England and sighted an RAF field near the coast. 1st Lt. Michael finally regained consciousness and insisted upon taking over the controls to land the plane. The undercarriage was useless, the bomb bay doors were jammed open; the hydraulic system and altimeter were shot out. In addition, there was no airspeed indicator, the ball turret was jammed with the guns pointing downward, and the flaps would not respond. Despite these apparently insurmountable obstacles, he landed the plane without mishap.”

Edward Michael, who grew up in the Norwood Park neighborhood, died in 1994 at the age of 76.

Twelve O’Clock High reflects the bravery and courage of those who fought for the cause of freedom. Its vivid recreation of air warfare and its depiction of men giving the maximum effort in defeating the enemies of democracy is an inspiration for all time. In today’s increasingly narcissistic society—where everything is “all about me”—a society that is also losing its sense of history and perspective, it is critical that we remember a generation that knew the meaning of collective sacrifice. They were our greatest generation, and to them this screening is dedicated.

I would like to thank George E. Schatz for his support and encouragement of tonight’s screening. George passed away this past Saturday, August 1st, at the age of 96. He died, like the High Lama in Lost Horizon, peacefully. In many ways, George was a national treasure. It is now up to us to carry on his legacy and keep the Spirit of ’45 alive.

~M.C.H.

Mr. Bill McNabola, WWII veteran

Mr. Nelson Campbell, WWII veteran

Slideshow presentation (featuring many rare behind-the-scenes photos from Twelve O’Clock High).