The following is a transcript of my presentation on Sullivan’s Travels at the Park Ridge Public Library on April 27, 2017.

Sullivan’s Travels is the story of a well-off motion picture director who wants to make a socially-conscious movie—against the advice of his studio bosses. Motivated by this idealism, John L. Sullivan sets out on a noble experiment dressed as a hobo in order to see how the other side lives. He’s well-intentioned, but misguided, and eventually all roads lead him back to Hollywood. In a diner, he meets a struggling young actress, and together they again attempt Sullivan’s expedition. It is only when he is stripped completely of his past and his own identity that Sullivan finds the road to self-discovery. Sullivan’s Travels is a movie where the optimism of Hollywood meets the bleak social reality of a country still feeling the Depression.

Preston Sturges is remembered today as being one of the great comedy directors from Hollywood’s golden age. A former Broadway playwright, he began his movie career as a screenwriter at Paramount before he moved into the director’s chair. He was one of the first writers to direct his own screenplays. His success ultimately empowered the role of the screenwriter and paved the way for other filmmakers like John Huston. Sturges’ films were known for their fast-paced dialogue and their physical comedy; Sullivan’s Travels, one of eight films that he directed at Paramount during his peak years between 1940 and 1944, is no exception. The idea of the picture formed as a reaction to the “preaching” he saw by other comedy directors who “seemed to have abandoned the fun in favor of the message,” he said in his autobiography. “I wrote Sullivan’s Travels to satisfy an urge to tell them that they were getting a little too deep-dish; to leave the preaching to the preachers.”

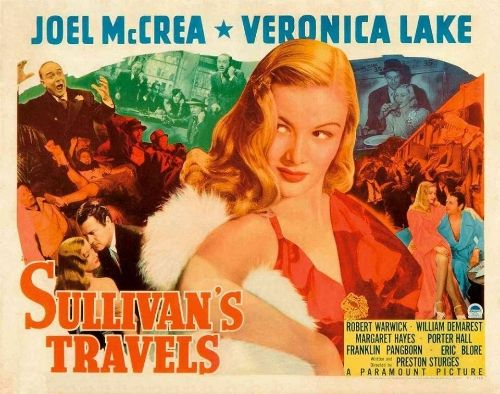

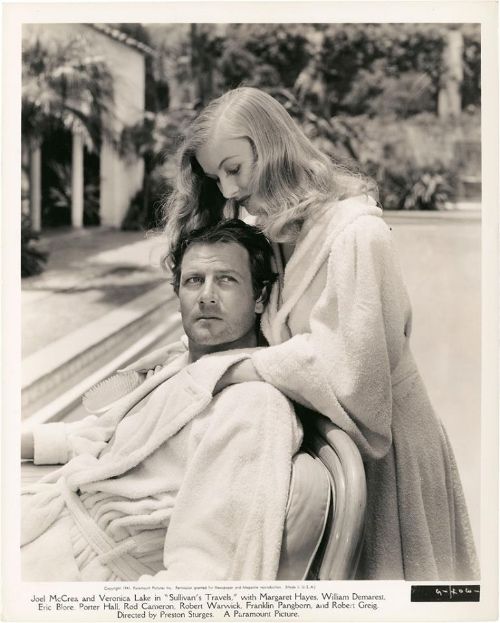

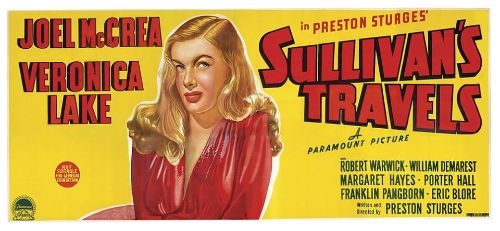

Sullivan’s Travels was the first of three films Joel McCrea would make for Preston Sturges. (The other two were The Palm Beach Story and The Great Moment.)McCrea was an actor movie audiences could always identify with, exuding qualities such as honesty and sincerity in all his roles. McCrea had crossed paths with Sturges a few times over the years, but one day at the studio commissary Sturges told McCrea, “I’ve written a script for you.” “No one writes a script for me,” McCrea replied. “They write a script for Gary Cooper, and if they can’t get him they use me.” McCrea loved the script, but he did not love working with his co-star.

Veronica Lake, at her peek-a-boo pinnacle, was Sturges’ choice from the very beginning– ever since he first saw her in 1941’s I Wanted Wings. Barbara Stanwyck and Frances Farmer were also mentioned, and Farmer had actually tested for the role of The Girl. What Veronica Lake failed to tell Sturges at the time was that she was six-months pregnant when shooting began. This did not go over well with the director, and for the rest of the production he tried to hide her pregnancy with the aid of costume designer Edith Head. Lake also was unprepared on set. “She wouldn’t know her lines,” McCrea had said. “This great dialogue and we would go through about fifteen takes while she was learning her lines. Then by the time she got it great, I was just going through the lines, kind of pooped out and tired. She was very unprofessional.” McCrea would later pass on the opportunity of working with her again in I Married a Witch. Fredric March took the role in that film and his experiences with her were no better. Despite the on-set drama, Lake gives one of her best performances in Sullivan’s Travels.

Around these two stars are many of Hollywood’s great character actors who were part of Sturges’ “stock company.” The director knew how to make use of all his ensemble cast on-screen. They were eccentric and had an identity all their own. It was as though the stars always had a family around them. These familiar faces included Robert Warwick, Franklin Pangborn, Robert Greig, Eric Blore, and the ever-present William Demarest once again cracking wise. Demarest would appear in a total of eight movies directed by Preston Sturges.

Sturges’ cinematographer on the film was John Seitz, who was one of the best cameramen in Hollywood. He shot such film noirs as This Gun For Hire, Double Indemnity, and Sunset Boulevard for director Billy Wilder. He would shoot two more films for Sturges: Hail the Conquering Hero and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek. In Sullivan’s Travels, Seitz’s lighting establishes many moods—from the brightly-lit studio scenes that reflect Paramount’s own glossy tone to the darker moments depicting two shadows passing through a shantytown. One of the virtuoso shots in the film comes early when Sullivan is pitching his “Oh, Brother, Where Art Thou?” idea to the studio brass. In order to save time and money, Seitz and Sturges were able to pull off the scene in one unbroken take. Though they would shoot it a few times, they were able to condense two days of work into one. It’s a shot that lasts over four minutes.

Sullivan’s Travels is a film that successfully mixes the genres of comedy and melodrama. What starts out like another madcap comedy becomes a distant cousin to John Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath and William Wellman’s Wild Boys of the Road. The film shifts moods as its main character discovers the real world and begins to understand his place in it. Sullivan has his epiphany in a church, but it’s not the religious conversion one might expect. The fable-like scene with the black congregation is the key sequence in the film, and here, the characters are treated with respect– not as racial caricatures. The preacher, played by Jess Lee Brooks, brings a dignity to his characterization.

The film is a wry satire on Hollywood, but it’s also a screwball comedy that shows a self-conscious use of Hollywood convention. For instance, the presence of Veronica Lake is itself a convention—a reminder that “There’s always a girl in the picture.” It’s as though John Sullivan were travelling through the antics of one of his own movies—a world designed of comic convention and slapstick. Here, there are stereotypes such as the buffoonish black cook getting tossed around in the land yacht during a chase scene. It’s a world as artificial as the rear-screen projection we see as Sullivan and the girl ride the rails.

But Sullivan can never quite cross into the realm of reality as himself. When he tries, slapstick adventures lead him back to Hollywood. However, when an injury forces him to forget his purpose and he is no longer a director on a mission, he then experiences life in a new way. When he awakes to find himself on a train, after being knocked unconscious, there is no longer the rear-screen backdrops. There’s a shot of McCrea actually on a train with natural sunlight on him. Perhaps now that he exists in this new state of reality, the black members of the church seem more human and are no longer movie stereotypes. John Sullivan has finally crossed into a world not defined by movie conventions. Ironically, it will take a movie plot twist to return him to where he naturally belongs. McCrea’s performance is extraordinary because throughout most of the film he acts with misguided intentions and lacks a true sense of understanding. He’s pretentious in his pitch to the studio, and perhaps condescending in his belief that the good poor can be paid off in $5 bills for helping him understand. But in his last scene, McCrea reveals the genuine sincerity movie audiences had come to expect from him. We the audience believe Sullivan has indeed been awakened.

In the revelation scene, it’s interesting that Sturges uses a Mickey Mouse cartoon in the church, but this was only after he had failed to get the rights to a Charlie Chaplin short. Chaplin had denied the request. As a result, the uproarious laughter at the Mickey Mouse screening is a little forced, and it might’ve played better with Chaplin. For one thing, in terms of theme, John Sullivan has become the tramp character audiences had once identified with in the silent movies. Curiously, Chaplin was himself one of those comedy directors who would be accused of “preaching” in his films, having recently made The Great Dictator which, like Sullivan’s Travels, depicted a grim world situation but made its points through humor. Also of note, and directly related to silent cinema, are the long stretches in Sullivan’s Travels where there is no dialogue. Such an occurrence was rare in a Sturges film which was always famous for its dialogue. Here, there are very emotional sequences where everything is conveyed visually through action, camerawork and music.

Sullivan’s Travels received mostly mixed reviews when it was released and did just okay at the box office. Like so many other movies we now call classics, its reputation grew over the ensuing decades. It’s now recognized as one of the great works of cinema. Sullivan’s Travels is not so much a story of Hollywood as it is a story of how an artist interacts with the real world—a world whose problems cannot be solved easily. This is a theme that persists today. What is the role of the artist in society? And how can the artist reveal truth? This struggle remains at the core of a medium which balances art with commerce. It’s also a movie about accepting one’s place in the world. You don’t need to make another Grapes of Wrath if your calling is to make people laugh.

In Movies About the Movies, author Christopher Ames writes of the film, “Sullivan’s Travels appears to endorse escapist entertainment over socially conscious films, but it actually makes a subtler distinction: it argues against didactic message films… in favor of films that use humor, wit, and satire to examine social problems. Sturges, though a satirist, is hardly a radical, but it would be a mistake to see this film (or his others) as strictly escapist. In his travels, Sullivan learns not only respect for comedy, but also respect for his audience.”

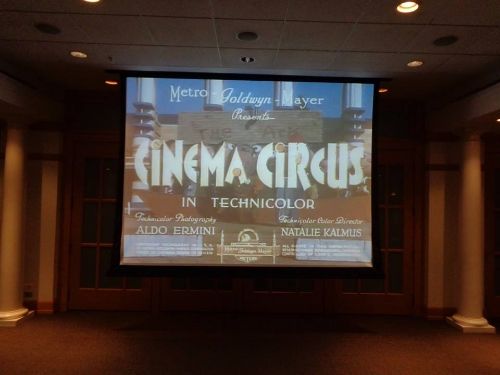

You never know what you might see before the show at the PRPL Classic Film Series!