WHAT: Rear Window (1954) on DCP/Season 5 Opening Night

WHEN: September 14, 2017 2 PM & 7:30 PM

WHERE: Pickwick Theatre, Park Ridge, IL

WHAT ELSE: Prelude music by organist Jay Warren at 7 PM; Halloween show preview

HOW MUCH: $10 ($8 advance before Thursday) or $6 for 2 PM matinee (feature film only)

“Always cunning, always operating on as many levels as he could plumb in a story, Hitchcock was at his most byzantine with Rear Window. Its obvious voyeurism was wrapped up with sympathetic humanism; its grisly crime story offered sharp-eyed character study and aching romance. Crafted entirely in the studio, claustrophobic in its staging, Rear Window was also Hitchcock’s greatest demonstration of Kuleshov’s theories of how editing affects perception– and by his own lights ‘my most cinematic’ film. One of his simplest, ‘smallest’ films, it is also among his most complex and universal.” ~ Patrick McGilligan, Alfred Hitchcock, A Life in Darkness and Light

The first Alfred Hitchcock film I ever saw was Rear Window. What adds to the memory is that it was experienced in a theatre. It was Thanksgiving, 1983, when my father took my brother and I to the Mercury Theatre in Elmwood Park. At that time, Hitchcock’s films were being re-released theatrically. As an eight year old, I was on the edge of my seat when I saw the hero’s girlfriend sneak into a neighbor’s apartment to look for evidence. Seeing the film on the big screen made such an impression on me that all these years later I am presenting it at the Pickwick Theatre in Park Ridge. The Pickwick Theatre Classic Film Series will open its fifth season on September 14 with James Stewart and Grace Kelly in what is Alfred Hitchcock’s most commercially successful film. Rear Window is one of the great thrillers of American cinema and is essential viewing.

Jeff (James Stewart) is a wheelchair-bound photojournalist who kills time watching his neighbors in the apartments across the courtyard. After observing some suspicious behavior coming out of the traveling salesman’s (Raymond Burr) unit, Jeff enlists the help of his girlfriend, Lisa (Grace Kelly), and the insurance nurse (Thelma Ritter) in trying to determine what is going on– and what became of the salesman’s wife, Mrs. Thorwald. As things intensify, Jeff calls in his detective friend (Wendell Corey) to investigate whether it was murder. Paralleling this storyline is the strained relationship between Jeff and Lisa.

The screenplay was written by John Michael Hayes and based on a 1942 Cornell Woolrich short story, “It Had to Be Murder.” (Woolrich later renamed it Rear Window in 1944.) It’s been suggested that the Jeff/Lisa relationship was inspired by the Robert Capa/Ingrid Bergman affair. Capa was a noted photojournalist like the character Stewart plays in the film, and like “Jeff,” Capa preferred being a bachelor. He did not want to marry a very eager Ingrid Bergman. Hitchcock, who had worked with Bergman, was struck by this idea of a man rejecting a seemingly perfect and, to Hitch, unobtainable woman. Hayes, however, maintained that the Lisa character was inspired by his own wife, who was a model.

Rear Window is a story about voyeurism and spectatorship. The main character is someone who would rather watch than participate. In a very real way, the film is a reflection of cinema itself with Jeff serving as a surrogate for us, the audience. He is in his own dark world, watching the action play out across the courtyard, the windows resembling theatre screens. To put it in modern terms, instead of “channel surfing,” Jeff is window surfing. The film deals with morbid curiosity, and like the moviegoer in the darkened theatre, we desire to see some kind of drama unfold before us.

Although not all of us have a room with a view like Jeff’s, the modern-day equivalent can be found in social media, particularly Facebook. As members scroll through their newsfeeds each day or watch “live” videos, they are complicit in voyeurism, watching the lives of their “neighbors” unfold on a daily basis. The “rear window ethics” are questioned in the film, and in today’s world we must also question the ethics of a communication tool that allows so much access and is susceptible to so much abuse. Rear Window is a film that deals with the consequences of looking. As Thelma Ritter’s Stella says in the film, “We’ve become a race of Peeping Toms.”

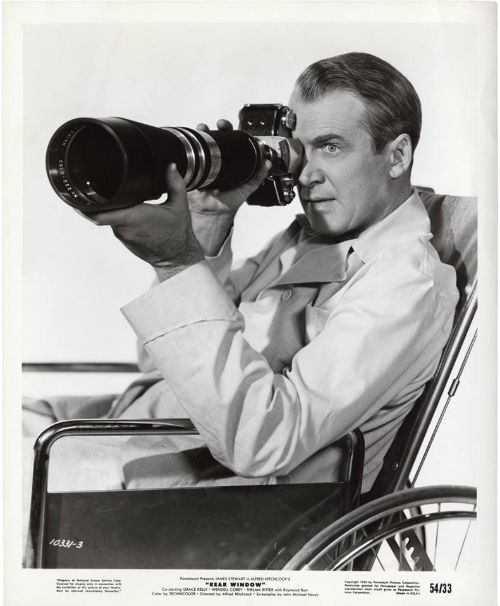

The wandering male gaze: James Stewart as the passive observer with the telephoto lens.

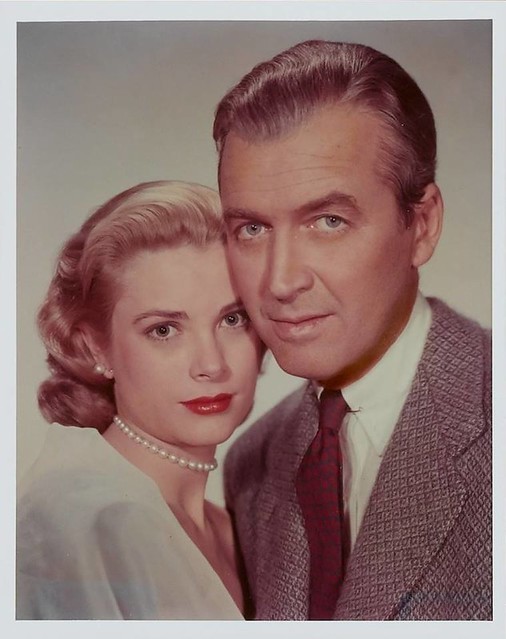

Grace Kelly was one of the most beautiful actresses in the movies, and throughout the 1950s she appeared in many classis such as High Noon as well as two other films for Hitchcock: Dial M For Murder and To Catch a Thief. Known for her perfect features and her cool, aristocratic bearing, Kelly was the ideal “Hitchcock blonde.” In the film, she makes one of the most striking entrances when she arrives at Jeff’s apartment and her shadow crosses over his sleeping face. When he awakes, we see Lisa in a close-up from Jeff’s point of view. Another visual delight are the costumes she wears that were designed by Edith Head– with input from Alfred Hitchcock himself. As a result, Kelly is like a high society model, sporting the latest in Paris fashion.

Kelly with our national treasure, James Stewart

One of the most memorable aspects of the film is the set where all the action is confined to one location: the Greenwich Village apartment (modelled after an actual building complex at 125 Christopher Street in New York City). With few exceptions, the action is seen strictly from Jeff’s vantage point, and we see no more of the neighbors’ apartments than he does. In this respect, the restricted space of the narrative recalls other Hitchcock films like Lifeboat, Rope, and Dial M For Murder (Hitchcock’s most recent film). The apartment complex was actually one of the most impressive sets built at Paramount since the peak years of Cecil B. DeMille. Its cost was 25% of the entire budget (compared to 12% for the cast salaries). The set measured 98 feet wide, 185 feet long and 40 feet high, and included 31 apartments. The “ground level” that is seen in the film was actually the stage basement. Within this vast stage, Hitchcock was able to communicate with his actors by way of short-wave radio. To make the filmmaking more efficient, the stage was pre-lit using a large console of remote-control switches. Rear Window had its share of complications for the crew to overcome, but it was the challenge of filming the material that drew Hitchcock to it in the first place.

Rear Window on a big screen is a wonderful experience, particularly for those who do not already know the story. But for those who have seen it before, there are always new rewards to be found in multiple viewings. When you already know the storyline, you can better appreciate the way and manner in which it is told. Particularly noteworthy are the film’s compositions and the details of the sets. There is also the effective use of natural sound– not just what we hear in the courtyard, but how Hitchcock associates it with the images on the screen; the audience will see one thing but hear something else. And there is the way Hitchcock tells the stories of his characters– orchestrating them like a great maestro– and we see a wide spectrum of male/female relationships, from Miss Torso and her many suitors to Miss Lonelyhearts in search of just one. There is great variety in who occupies the apartments, but it is fascinating to see the ways they are linked. The mood of one scene carries over into another. The mood in Jeff’s apartment parallels that in the rooms across from his.

Rear Window may have the commercial gloss of a film made in the classical Hollywood style, but it is also an intricate work that has much to say about human curiosity. For more about the making of Rear Window and its influence on contemporary cinema, I recommend Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (2000), a collection of essays edited by John Belton.

~MCH

Stewart and Kelly with Hitchcock on the set of his small universe.