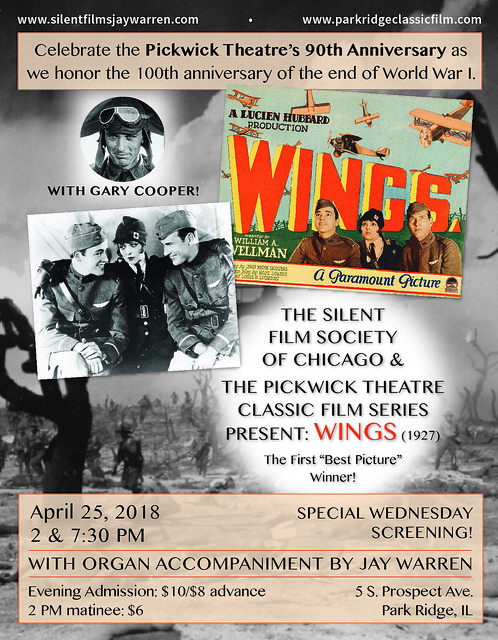

WHAT: Wings (1927) DCP restoration with 10 min. intermission

WHEN: April 25, 2018 2 PM & 7:30 PM

WHERE: Pickwick Theatre, Park Ridge, IL

WHAT ELSE: Jay Warren provides organ accompaniment at both screenings on the Pickwick’s original 1928 Mighty Wurlitzer.

HOW MUCH: $10/$8 advance or $6 for 2 PM matinee. Click Here! for advance tickets for the 7:30 screening.

“Ironically, a mass-market silent spectacular like William Wellman’s Wings effortlessly showcases far more visual artistry than mainstream American films have offered since: it displays shifts from brutal realism to nonrealistic techniques associated with Soviet avant-garde or impressionistic French cinema– double exposures, subjective point-of-view shots, trick effects, symbolic illustrations on the titles, and so on.” ~ Author Scott Eyman, The Speed of Sound: Hollywood and the Talkie Revolution 1926-1930

It’s been over ninety years since Wings (1927) first soared across movie screens, but the passage of time has done nothing to dim the film’s power to captivate. Directed by the legendary William “Wild Bill” Wellman and featuring an all-star cast including Clara Bow, Wings is a saga of war, love, and friendship. The film is a grand spectacle with some of the most remarkable aerial photography ever recorded for a motion picture. Wings was Paramount’s most successful film of the year and is now recognized as one of the last great films of the silent era. To honor the film and commemorate the centennial of the end of World War I, the Silent Film Society of Chicago and the Pickwick Theatre Classic Film Series have teamed up for a special Wednesday screening on April 25, 2018. This year also marks the 90th anniversary of the Pickwick Theatre, so what better way to mark the occasion than with a silent movie!

In the mid-1920s, Paramount Pictures, headed by Adolph Zukor and Jesse Lasky, was the most ambitious studio in Hollywood. In 1926, Lasky was looking for his next big roadshow picture. The roadshow was a studio’s prestige picture for the year, typically debuting on a city-by-city basis. One day after being introduced to John Monk Saunders, author of Wings, Lasky knew he had found his story. Saunders’ tale of World War flyboys stuck with Lasky, and he in turn proposed it to his partner. Zukor, however, was deeply concerned about the cost of making a film of such scope. It would require a prodigious amount of equipment and manpower.

To solve the dilemma, the studio enlisted the aid of the War Department. Lasky and Zukor felt the government could provide the necessary materiel. Being a former pilot himself, Saunders tried to get funding for the studio but only got entangled in red tape. Lasky then sent his producer, Lucien Hubbard, to Washington to help Saunders secure military assistance. Realizing the benefits and recruiting power of the movies, the U.S. Army agreed not only to supply the equipment and men but the location as well. The film’s outdoor scenes would be shot in San Antonio, Texas, near the Kelly Flying Field and Camp Stanley. It’s been estimated that the War Department supplied over $15 million dollars worth of materiel to the production, including tanks and “aeroplanes.” (By today’s standards, that would make Wings the most expensive film ever made.) The logistics alone would be daunting for this film, so the producers needed to find the right director– preferably one with air experience.

Buddy Rogers, Richard Arlen, and Gary Cooper

B.P. Schulberg, who was in charge of production, pushed for thirty year old William A. Wellman. Wellman originally got his start in Hollywood as an actor thanks to Douglas Fairbanks, but Wellman hated seeing himself on the screen and instead turned to directing. At the time that Wings was green-lit, Wellman was under contract to Paramount and had already made eleven films in his career, mostly B Westerns. Though he didn’t have experience with big productions and certainly didn’t have the name recognition of a Cecil B. DeMille or a Victor Fleming, Wellman did have the necessary background as a pilot. In fact, he had flown in the famous Lafayette Escadrille of the French Foreign Legion and had combat experience in World War I. As a result, he gave Wings its authenticity. Wellman had seen men die in war and he certainly knew more about it than any of the studio men. He was a no-nonsense filmmaker and was determined to make “the best goddamn picture this studio had ever had.” This was his big chance to prove himself. Wellman’s conviction sold Lasky.

The original plan was to make Wings an all-star production. Paramount was on the right track with Clara Bow. Famous for being the “It Girl,” Bow was the biggest female star in the world. There was no one more popular with movie audiences. She was a Paramount star and was cast early on in pre-production. Though the original story was based on John Monk Saunders’ unpublished story about the U.S. Army Air Service– he later wrote the novelization of the film version– the writers of the screenplay, Hope Loring and Louis Lighton, tailored it to Clara Bow. Bow was cast as the “girl next door,” Mary Preston, who is in love with the story’s main hero, Jack Powell. Of her part, Bow later said, “Wings is a man’s picture and I’m just the whipped cream on top of the pie.” Though her role may have been decorative, she is lively and exuberant and gives it everything she has. (There’s even a flash of nudity from Clara in a Paris hotel room!)

For the male leads, Paramount supposedly wanted Charles Farrell and Neil Hamilton while producer Lucien Hubbard considered twenty-three year old Charles “Buddy” Rogers over Farrell. At some point, Wellman asserted himself in these casting decisions and pushed for the two relative unknowns in the main roles: Buddy Rogers was cast as Jack Powell and Richard Arlen took on the role of Powell’s rival, David Armstrong. Initially, Wellman passed on Arlen until he saw a screen test of him. It was only then that he believed Arlen could be a handsome leading man. Whether this was a factor or not it’s hard to say, but one benefit of casting an unknown actor is that he is more likely to do what is asked of him.

In the role of the flying cadet who is killed in training, Wellman picked twenty-five year old Gary Cooper. Coop was chosen out of 35 other actors who tested for the part. (He may have been helped by Clara Bow, whom he was having an affair with at the time.) Wellman felt Cooper had charisma and liked him so much that he kept him on location even after his brief scene had been shot. This is the role that launched Gary Cooper’s career. In the role of Sylvia Lewis, the hometown girl both Jack and David are in love with, is Jobyna Ralston. Ralston is best known to movie fans as Harold Lloyd’s leading lady in some of his best comedies. She had signed on at Paramount as a freelance actress. During production, Ralston fell in love with her leading man, Richard Arlen, and the two would marry shortly afterward in 1927. Comedy relief in the film is provided by El Brendel, a dialect comedian from vaudeville who played mostly comical Swedes in the movies. (He was not actually Swedish.) Also in the cast is Hedda Hopper, who later became a gossip columnist, and Henry B. Walthall, one of the fine dramatic actors of the silent era. In bit parts, Wellman cast his wife, Margery Chapin, and adopted daughter as the French farm woman and her child. Wellman had his own cameo in the film playing a dying doughboy: “Attaboy! Them buzzards are some good, after all!”

To recreate a world war, Paramount essentially built France in San Antonio. They designed, among other things, a French village (comprising of thirty-five buildings) and the Saint-Mihiel battlefield. Fortunately, the production had access to more than enough men to populate the sets. In fact, Fort Sam Houston, which the studio made use of, had the largest garrison of troops in the United States. It has been reported that the production required over 200 aircraft (including observation balloons brought in from Illinois). The main scout aircraft used in the film were Thomas-Morse MB-3s (representing American SPADs) and Curtiss P-1 Hawks that were turned into German planes. The filmmakers had permission to use a 5-acre parcel of government land to stage the battle scenes. This area was prepared prior to the arrival of the cast. Trenches were dug and the land was made ready by the Army who used it as target practice. Additionally, four towers were erected for the cameras as well as for the staging of the Battle of Saint-Mihiel; a system of flag signals would direct the action on the ground. The sequence included 3500 infantrymen. (Many of the extras in the film came from the 2nd Infantry Division and the Texas National Guard.) With so many men on the scene and so much action to coordinate, including explosions and airplanes, timing was everything. As a result of Wellman’s attention to detail in these visceral action sequences, Wings doesn’t just take the audience into the air but pulls them down into No Man’s Land as well.

In this video (5:40), Wellman talks about the shooting of the film’s gigantic battle sequence. It was done in one take that lasted five minutes!

Wings is a film of great technical prowess– perhaps nowhere more so than in its aerial photography. Harry Perry was the main cameraman during filming. (Perry would later photograph 1930’s Hell’s Angels for Howard Hughes). There were thirteen cameramen on the picture, and Wellman made a point of finding men who had experience in the air. E. Burton Steene, considered to be the #1 aerial photographer of his day, was said to have shot 90% of the scenes in the air. (He also worked on Hell’s Angels prior to his death in 1929.) To capture the footage in the sky, the cameramen used an Akeley camera that was specifically designed for the air. For a video about this fascinating machine, Click Here! Additionally, some of the most talented stunt flyers of the era performed in the film. Wings would not have been the success it was without pilots like Dick Grace, who was the greatest stuntman of the era. Flyer Frank Clarke was able to capture the startling footage of his plane going into a spiral– with the camera trained on himself! The formation flying was all performed by the Army Air Corps pilots on base, but no Army pilot would’ve attempted the outrageous maneuvers performed by the stunt flyers. For more about these daredevils and their exploits in film, Click Here!

The lasting success of the film depended not just on the stunt flyers but on the cast as well. Wellman wanted this film to be realistic, and so he did not want to “fake it” with pilots photographed from the ground. Before Wings, no actor had ever been photographed in the air before. To accomplish this, the filmmakers resorted to trial and error. During the first two months of production, the cameramen originally tried to shoot the planes in the air using a hand-cranked camera, but as the planes were violently buffeted by wind and the camera would shake, the footage was unusable. Ultimately, the problem was solved by the engineering contribution of Wellman’s military advisor, 2nd Lt. Clarence S. Irvine. Irvine helped create the camera system that enabled close-ups of the actors. Motorized cameras (not the hand-cranked ones used on the ground) were bolted to the front of the plane (or strapped to the engine cowling) so that the cameras could be trained on the pilots. This necessitated the pilots (who in many cases were the actors) to operate the cameras themselves!

Although a safety pilot was onboard in the second cockpit, he would have to duck down while the camera was running. The actors had to regulate the camera for their close-ups and fly the plane for the duration of the shot. For the length of 500 feet of film, the actor did everything– act, shoot (the camera), and pilot. Richard Arlen had some flying experience as part of Canada’s Royal Flying Corps, having flown planes as a crewman to the front lines in the war. Buddy Rogers, on the other hand, had never been up in the air before. Each took flying lessons before filming began. Rogers, for instance, spent nearly a hundred hours in the air during the course of his scenes. He did not have the stomach for flying and often got sick by the time he returned to the ground. In the eyes of Wellman, it was a gutsy performance by Rogers. As a result, Wellman held him in high regard for the courage he displayed in the making of Wings. It would be almost inconceivable that Paramount (or any other studio) would’ve allowed one of their major stars to take these risks.

During the course of production, Wellman tried the patience of the studio men. There were days when there was simply no shooting, and at one point, the crew went 18 days without shooting anything in the sky. To his credit, Wellman was simply waiting for the clouds. These delays added to the expense of location shooting, but he knew his film needed the perfect backdrop. To Wellman, the clouds created the illusion of speed and made everything more dramatic. The footage of the planes flying against the clouds or disappearing amongst them during the dogfights would not have been as effective without a perspective for the planes. At one point during the shoot, Paramount sent an executive out to the location to complain about the mounting expenses. Wellman reportedly told the man he had two options: “a trip home or a trip to the hospital.”

When the production returned to Paramount, Wellman completed the indoor scenes. One of the most famous shots in the film– and in all silent cinema, for that matter– comes in the scene at the Folies Bergere in Paris. There is a long shot of the camera traveling through a crowd of seated patrons. This was created by having an overhead track with the camera attached to it. With E. Burton Steene as the operator, the camera was able to dolly from one end of the room to the other. Wellman and Steene had intended on using another dolly shot later in the film depicting Buddy Rogers and Clara Bow walking down a street. However, before the shot was completed, Steene suffered a heart attack.

Richard Arlen with director William Wellman

In an era where a million dollars was considered expensive, Wings cost $2 million to make– and nine months to complete. The film premiered on August 12, 1927, at the Criterion Theatre in New York. Upon its release, it became an immediate sensation. Being an event picture, it was presented, in most cases, with a full orchestra, sound effects, and in Magnascope (an early widescreen process that had been used for Paramount’s 1926 film Old Ironsides). Added to its visual appeal was the film’s use of tinting (a familiar element in silent movies) and Handschiegl color (colored sections of the frame seen in various shots of explosions and flames).

At the first Academy Awards ceremony in 1929, Wings won for Best Picture (although William Wellman was not nominated for director). In its initial run, Wings played for sixty-three weeks across the country. It would later be re-released in 1929 with a synchronized musical score. William Wellman went on to direct a slew of some of the best “pre-Code” films in the early 1930s as well as films like The Public Enemy, Nothing Sacred, A Star is Born, Beau Geste, and The Ox-Bow Incident. Over the course of his long and varied career, Wellman’s films received 32 nominations and 7 Oscars. But he always insisted that he was most proud of Wings.

There were great aviation films that followed. This was the Charles Lindbergh era when flight was all the rage. Howard Hughes made Hells’ Angels, but his aviation epic lacked the acting talent that Wellman had through Paramount. The Dawn Patrol was another important film which was also written by John Monk Saunders; he won an Academy Award for its story. Saunders later worked on the screenplay for the brilliant The Last Flight (based on his novel Single Lady), a story of The Lost Generation and ex-flyers. The film’s aircraft scenes were borrowed from The Dawn Patrol.

Wings resonates not just because of its technical splendor but because of its raw emotions.The relationship between the two main leads, and their final scene together after one is shot down, is deeply emotional. It’s a scene of great sadness and power. Wings wasn’t made by someone removed from war, as today’s filmmaking fanboys are, but by a man who had lived it. Wellman experienced those types of friendships and knew how they were forged in battle. He infused the film with a realism that strengthened the character dynamic. As a result of Wellman’s own life experiences, his film shows a great sensitivity, particularly in the early scenes in which family and home are left behind. Young men leave with boyhood enthusiasm and a strong determination that will be put to the test. A film of pure emotion, Wings is a great work about life and death. After ninety years, it’s a picture that continues to soar above the rest.

~MCH

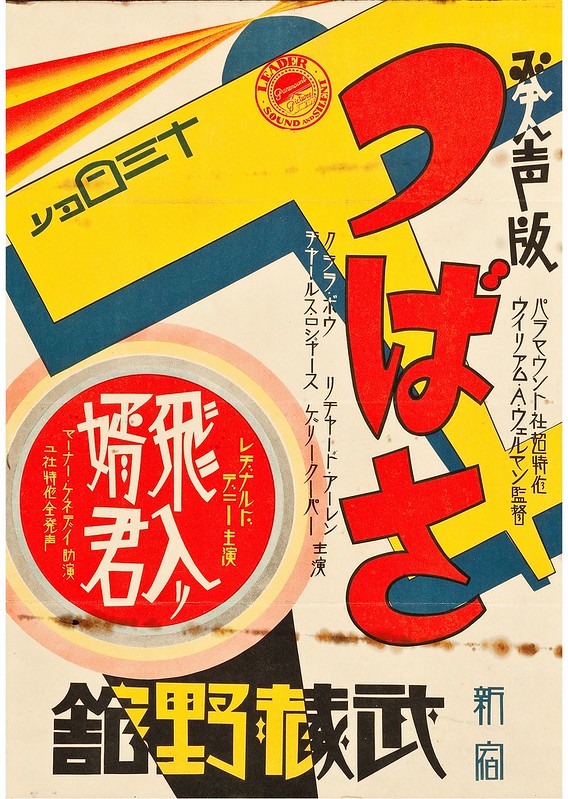

A stunning, 1930s reissue poster from Japan.

A publicity photo of Clara Bow advertising Wings. (Though Wings doesn’t quite capture the fashions and hairstyles of 1917–instead settling for the style of the late 1920s– Clara does not actually wear this modern aviatrix outfit in the film! Interestingly, Edith Head did design her actual costumes. This was one of Edith Head’s first films as costume designer.)

A trailer for our April screenings: The Sound of Music & Wings. Thank you to our projectionist, Jerry, for putting these together!