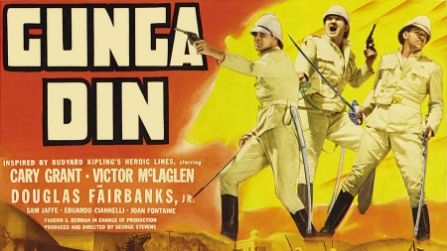

WHAT: GUNGA DIN: A 75th anniversary screening

WHERE: Pickwick Theatre, Park Ridge, IL

WHEN: January 23, 2014, 7:30 PM

Presented by the Pickwick Theatre Classic Film Series

“We spent many weeks in the California desert at Lone Pine, several hours’ drive from Los Angeles, close to the base of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. According to the technical directors, the setting was much like India’s Northwest Frontier. It took at least a month to build a tent city for hundreds of us to live in. The director, principal actors, first cameraman (the award-winning Joe August), writer Joel Sayre, and senior technicians either had tents of their own or shared with one another. Every day we worked in temperatures that sometimes rose to 110 in the shade. George, Bob Coote, Cary, Joel Sayre, and I would sit up after dinner telling stories, discussing politics, and arguing about and/or rewriting scenes to be done the next day. These sessions were usually enlivened by a few drinks to warm up the chatteringly chill desert night air that followed the blistering hot days.” ~ Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., The Salad Days

We’re sounding the bugle for the “Films of 1939” and leading off with one of the greatest action films Hollywood ever produced. Few films, then or now, have been able to match Gunga Din‘s combination of humor, derring-do, and humanity. It’s a boy’s adventure about heroics that takes us back to our youth and rekindles old enthusiasms. It’s the sort of mythic dream that Hollywood excelled at in its golden age. Gunga Din‘s lasting influence can be seen decades later in 1984’s Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, which lifted many plot points from the earlier film. Gunga Din will continue to influence new generations of fans and filmmakers. Screened again in its 75th anniversary, it is clear that Gunga Din has lost none of its audience appeal.

Cary Grant, Victor McLaglen, and Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. play three soldiers hell-bent on making the world safe. When an English cavalry patrol at Tantapur, India, gets wiped out, Sergeants Cutter (Grant), MacChesney (McLaglen), and Ballantine (Fairbanks, Jr.) ride in and fight a murder cult of Thuggees. Gunga Din (Sam Jaffe) is the company water-bearer who dreams of being a soldier but must always follow behind. When treasure-hunting Cutter goes off in search of a golden temple, he and Gunga Din stumble into the meeting place of the Thuggees and their sinister Guru (Eduardo Ciannelli). Din escapes and brings word to the other sergeants, who must come to Cutter’s rescue.

“Tho’ I’ve belted you an’ flayed you,

By the livin’ Gawd that made you,

You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din!”

Gunga Din transports us to a romanticized era during the British Empire. It was inspired by the 1892 poem by Rudyard Kipling. However, the screenplay owes more to Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur. They were not the first writers to work on the project. RKO’s involvement in the property went back to 1936 when they purchased the story from producer Edward Small. Small had earlier acquired the rights from Kipling’s widow and had commissioned William Faulkner to write a treatment. However, Faulkner’s early drafts bear little resemblance to the 1939 film. When Hecht and MacArthur took over in 1936, they fashioned a tale that had the spirit of another Kipling story, Soldiers Three (1888). Additionally, they borrowed a plot element from their 1928 play, The Front Page. This newspaper drama had one character breaking ranks in order to get married.

The Hecht-MacArthur story had many of the themes associated with Howard Hawks, such as the camaraderie among men in battle. Hawks was the obvious choice to direct and was working with his frequent collaborators until the writers left the project in early 1937. Though Hawks was still attached to Gunga Din, he had recently gone over budget on Bringing Up Baby and had developed a reputation at the studio for being slow. Instead, production manager Pandro S. Berman chose George Stevens, a director known for bringing his films in on time and under budget. The irony, as Berman would soon discover, was that Stevens became slower than Hawks.

George Stevens, who was born in 1904 to a theatrical family, began his career in the movie business as a still photographer. In 1923 he became an assistant cameraman with Hal Roach, and by 1927 he was a full-fledged cinematographer. He would go on to shoot twenty-four Laurel & Hardy shorts. He also worked with Charley Chase, Harry Langdon, and the Our Gang kids. In 1933 he began directing. Some of his early films included Kentucky Kernels (with the comedy team Wheeler & Woolsey), Alice Adams, and Swing Time with Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. In later years, Stevens made such popular classics as A Place in the Sun, Shane, and Giant.

In Fairbanks, Jr.’s later years, he recalled this filmmaking giant:

“George Stevens was quite unlike the conventional, overassertive director. He appeared always to stroll about with a lazy sailor’s swagger instead of walking like other people. One’s first impression was that he was vague, dreamy, and inefficient, but actually this was an effective mask behind which his creative brain ticked at the speed of light. He confided his ideas in advance only to his cameraman, his scriptwriters, his first assistant, and his principal actors. His producers were often led to believe one thing when he really had something quite different in mind.”

George Stevens wanted Gunga Din to be an outdoors picture. The original Hecht-MacArthur story, however, was primarily set in the barracks. Stevens, along with writers Joel Sayre and Fred Guiol, rewrote the story to fit his vision of what the adventure should be. There were bits of business that Stevens invented on the spot and worked into the action. New scenes were often created the night before they were shot. Because of this method, his action scenes had an energy and a life they might not have had otherwise. Stevens had learned to improvise in silent screen comedy, and this carried over into what he called cavalry-scale improvisation. Of the whole, Stevens said, “It has a variety of moods, movements, and it has a rather definitely arranged structure, to hold interest together.”

Brave Soldiers

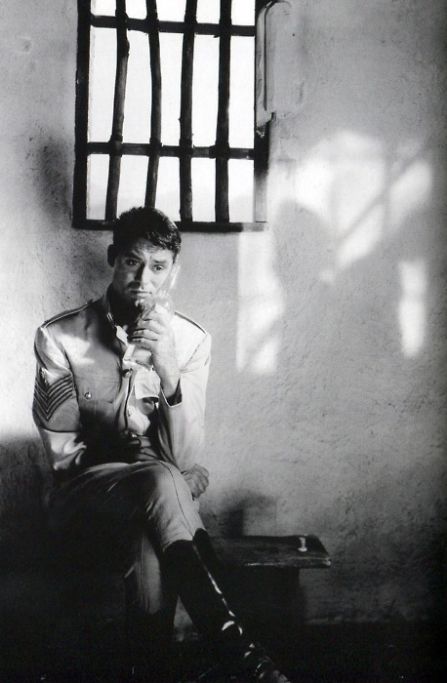

Cary Grant was considered for one of the principal roles early on in the film’s development. In fact, the studio may have had him in mind from the very start. Grant had a non-exclusive contract with RKO and had previously starred in Bringing Up Baby for Howard Hawks. Grant would become one of the most iconic faces in Hollywood– and the very definition of a movie star. Born in 1904, Archibald Alexander Leach, as he was then called, grew up in a working-class section of England. He was drawn to the British stage at an early age and would join a stock company of comedians. By 1927 he was appearing in America on Broadway. His first big break in the movies had come at Paramount when Mae West selected him for two of her vehicles: She Done Him Wrong and I’m No Angel. Grant had wanted to do Gunga Din but only if he could play the cockney character, Cutter, instead of the romantic Ballantine. Grant got his wish and was able to showcase his comedic abilities to great advantage, as when he’s strutting his way through a temple full of assassins.

Victor McLaglen was borrowed from 20th Century-Fox to play the older MacChesney. McLaglen had made a career out of playing tough enlisted men who usually had a soft spot under the hardboiled exterior. These types of characters appeared in films like What Price Glory, which was the first of his teamings with Edmund Lowe and proved to be McLaglen’s biggest success in the silent era. Similar roles were seen in The Black Watch and Wee Willie Winkie– both for John Ford. In fact, McLaglen was cast in many Ford films thoughout his long career, including 1934’s The Lost Patrol and 1936’s The Informer, for which he won an Academy Award for Best Actor. McLaglen’s real life was as interesting as any character he had played in the movies. Born in England in 1886, he left home at the age of 14 and managed to get into the British Army. This is where he learned to box. He would later tour Canada as a prizefighter. He travelled in Wild West Shows that paid $25 to anyone who could go three rounds with him. In 1909 he fought Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight champion, in an exhibition bout. After serving in World War I as a captain in The Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment, he turned his attention to the British cinema. In 1920, he made his first appearance onscreen in a career that would last into the 1950s with films like The Quiet Man (1952).

Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. never became the legend his father was, but he was a finer actor and a better romantic. A lifelong Anglophile, Fairbanks, Jr. could easily be mistaken for English but was in fact American. (He later became a decorated Naval officer during World War II.) Cary Grant had suggested him for Gunga Din, and according to film historian Rudy Behlmer, Fairbanks, Jr. was added to the cast only a week before production started. It’s been noted that Grant had wanted the role that was originally intended for Fairbanks. However, in his autobiography, The Salad Days, Fairbanks comments on Grant’s magnanimous nature as an actor– offering to take whatever part Doug did not want. Fairbanks goes on to say the issue was settled with the toss of a coin.

But Grant may not have been all that generous. In Cary Grant: A Touch of Elegance, Warren Gites writes, “… Grant deliberately cheated Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., out of one of the most memorable moments in the picture. In a rooftop scene, Fairbanks had to wrestle with a native, pick him up and hurl him into the street below. Grant coveted the bit himself, so he told his co-star, ‘Doug, you really shouldn’t do this. It looks like you’ve killed the guy. It wouldn’t help your image. And you know your father would never have done such a thing on the screen.” Fairbanks changed his mind and when Stevens asked for a volunteer to do the shot, Grant stepped forward. (We could easily imagine a Cutter-esque grin on his face.)

The casting of the three principals as the comrades in arms turned out to be ideal. Together, they are the three musketeers of Her Majesty’s Army. Each conveys a boy’s enthusiasm for adventure. That, and the genuine friendship among them, is at the heart of the movie. They give us the impression on screen that they’ve known each other for years and have already had many brawling adventures prior to our first glimpse of them.

Also is the cast is Joan Fontaine, who recently passed away last December at the age of 96. Her part in Gunga Din is a rather thankless role, but this is not a woman’s picture. Her primary function is to charm Ballantine “like a snake” and lead him astray into the tea business. At this point in her career, Joan Fontaine was not yet a star. The RKO brass had been grooming her to be one with films like 1937’s A Damsel in Distress. However, they ultimately determined she had “little promise” and subsequently released her from her contract. A couple years later she starred opposite Laurence Olivier in Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca.

“Very regimental, Din.”

The role of the Indian bhisti, or water-carrier, is played by character actor Sam Jaffe. Originally, the producers wanted Sabu, who had made his film debut in 1937’s The Elephant Boy. However, the young Indian actor could not be loaned out as he was about to star in Alexander Korda’s remake of The Thief of Bagdad. Jaffe, on learning this, chose to play the role of Gunga Din the way he felt Sabu would’ve played it. This could’ve been a legitimate regret in casting had Jaffe not been up to the challenge. But what he lacked in authenticity– Jaffe was a New York Jew, not an Indian– he made up for in the sincerity of his performance. Despite the age gap– Jaffe was 47 years old– he played the role perfectly. Jaffe brings nobility to the character while conveying a genuine desire to be a soldier too. After the mortally wounded Din tells Cutter, “The Colonel’s got to know!”– repeating Cutter’s own words from earlier in the film– his ascent up the temple tower with bugle in hand becomes one of the most powerful moments in the film.

The wonder of Gunga Din is how it deftly balances the lighthearted moments, such as the punch bowl sequence or Annie the elephant, with the more dramatic scenes. There are some genuinely ominous moments in Gunga Din which make it something more than just a comedy. One recalls the Thuggee henchman, Chota (Abner Biberman), yelling out the name of the Hindu goddess Kali, and then off in the distance we hear it answered back by an unknown number of Thuggees. Likewise, the action romp of the opening sequences is counterbalanced by the more serious nature of the spectacular final battle.

Gunga Din was shot by Joseph August. He was the perfect choice to photograph the outdoors picture that Stevens had wanted. August shows off the landscape to such great advantage– using California’s Mt. Whitney as a substitute for the Khyber Pass. Many Hollywood films that were set in exotic parts of Asia were shot in Lone Pine– 225 miles northeast of Los Angeles. But few were as carefully photographed as Gunga Din with its natural lighting and well-suited locations.

Legendary composer Erich Wolfgang Korngold was RKO’s first choice to score the picture, but he turned it down because he felt there was not enough time for him. Alfred Newman, with only three weeks, produced an original score that is both soaring and dramatic. Newman was one of the great pioneers in film music. In 1939 alone he did the scores for such films as Drums Along the Mohawk, Wuthering Heights, and The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

Gunga Din was a big picture for RKO. In fact, it would become the most expensive movie they ever made up until that time with a budget over 1.9 million. Originally slated for 64 shooting days, the schedule ballooned to 104 days. It’s no surprise that Stevens made himself scarce when Pandro Berman came visiting the location set during production.

After three previews, Gunga Din finally premiered at the Radio City Music Hall on January 26, 1939. It was released to the general public in February. Gunga Din was a hit with audiences and critics alike. The New York Times (Jan. 27, 1939) had this to say: “All movies… should be like the first twenty-five and the last thirty minutes of Gunga Din, which are the sheer poetry of cinematic motion. Not that the production as a whole leaves anything to be desired in lavishness and panoramic sweep. The charge of the Sepoy Lancers, for example, in the concluding battle sequence, is the most spectacular bit of cinema since the Warner Brothers and Tennyson stormed the heights of Balaklava…”

It did well abroad– except in India where the film was banned as Imperialist propaganda. Owing to its high cost, it did not immediately recoup its expenses. Gunga Din didn’t make a profit until its first re-issue in 1941. Since it is such a crowd-pleaser, Gunga Din has been released many times since. The 1954 re-release, unfortunately, pared the film down to 94 minutes. Recent revivals have restored Gunga Din to its full 117 minute running time.

Gunga Din is a Hollywood essential. It’s intelligently crafted and extremely fun. Everything fits together so perfectly it could never be remade. (There was never a sequel, although Blake Edwards wrote a comedic homage to it in the 1968 Peter Sellers comedy, The Party.) Gunga Din is one of the highlights of 1939– and certainly one of the most entertaining films of all-time. Please join us on January 23 when our expedition begins.

For much more on the making of this film, refer to Rudy Behlmer’s wonderful commentary on the 2004 dvd. Also in the supplemental features are color home movies that George Stevens had taken on location on 16mm.

Until his death in 2000, Fairbanks, Jr. remained the epitome of class.