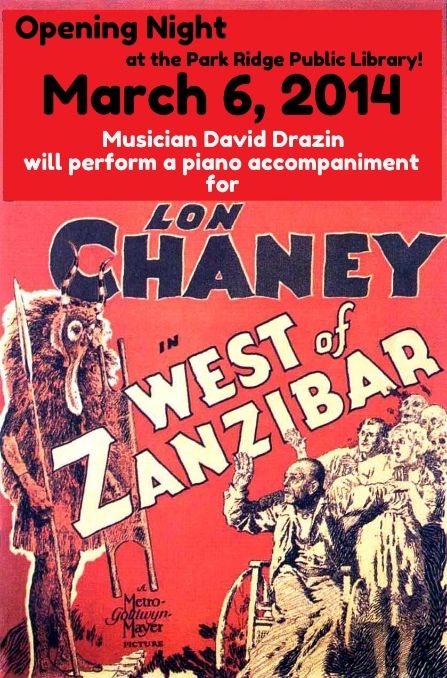

When: March 6, 2014, 7:00 PM (Doors open at 6:20 PM.)

Where: Park Ridge Public Library, 20 S. Prospect Ave. Park Ridge, IL

***With live piano accompaniment by David Drazin!***

Short: Lon Chaney: A Thousand Faces (2000) Starts at 6:20 PM.

“He made me this thing that crawls… now I’m ready to bite!”

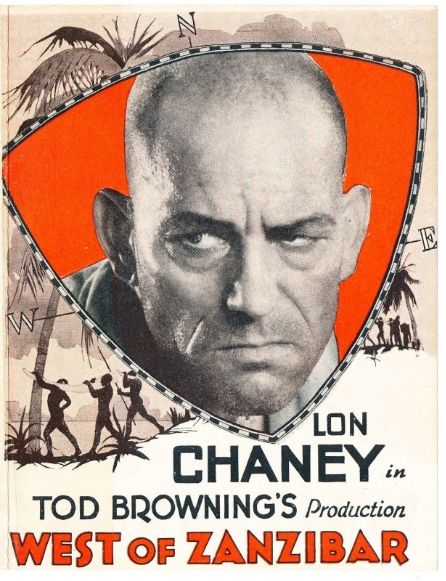

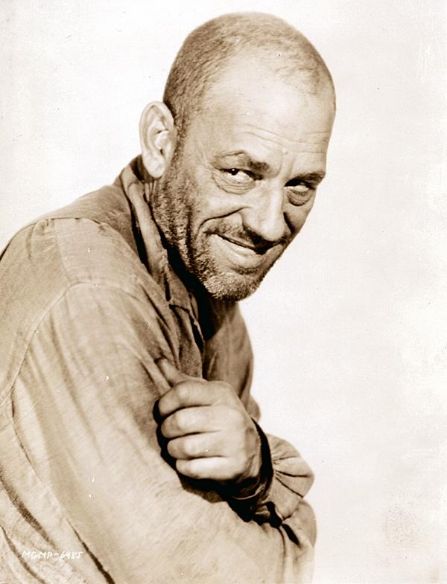

West of Zanzibar was the second to last collaboration between two masters of the macabre: director Tod Browning and star Lon Chaney, Sr. Their films often dealt with outcasts who are wronged by society or by women. Chaney himself was an outsider by Hollywood standards. This certainly added to his enigma. He always insisted there was no Lon Chaney outside of his roles. He may not have led the life of a movie star, but Lon Chaney was the most versatile actor in the business. One could argue he was the greatest actor in silent cinema. In West of Zanzibar, he gives one of his finest performances in a role that runs the gamut of emotions. It’s not one of his signature films, such as The Phantom of the Opera, but it is one of his best.

Chaney plays Phroso, a music hall magician who is completely devoted to his wife, Anna (Jacqueline Gadsdon). Her emotions tell us another story. When she returns to her dressing room we see what she is hiding. Waiting for her is her lover, Crane (Lionel Barrymore). He wants to take her away, but she doesn’t have the heart to tell her husband. The task falls to Crane, and in the physical altercation that follows, Phroso is thrown over a second-floor railing and is paralyzed upon his landing. Months pass and word comes to him that his wife has returned. He finds her body near the altar in church, and with her is a baby daughter. At this point, Phroso vows revenge against the man who stole his wife. He will also punish the love-child Anna had with Crane.

Years pass and we see Phroso– now known as “Dead Legs” Flint– fooling the African tribe with stage magic and a box of tricks. He reigns over the natives and his jungle empire like a twisted king– a white master who can cast out evil spirits. It is within this seting that Dead Legs puts his devious plan in motion. His rival, Crane, is an ivory trader in Africa, but his ivory is mysteriously stolen. Dead Legs then sends out a henchman to town to retrieve the girl (Mary Nolan), now eighteen, who has been deliberately raised in a brothel. All this is part of Dead Legs’ scheme to unite her with her father before destroying them both with the law of the jungle.

West of Zanzibar was based on a 1926 Broadway play called Kongo, written by Chester De Vonde and Kilbourn Gordon. Writer Bret Wood notes that the story “was inspired by a trip through the Congo taken by De Vonde (a noted repertory stage actor). According to a newspaper report, De Vonde contracted an ‘incurable tropical disease’ during his jungle excurion, and the quest to bring the play to film became an intense desire in his final days. On January 10, 1928, De Vonde died, without realizing his goal. Two hours after his death, MGM purchased the motion picture rights for $35,000.”

Walter Huston played the role on stage and would later recreate it in the 1932 remake, Kongo. In the play, the girl was battling a social disease, but this was changed to alcoholism for the movie since the censors would’ve eliminated any mention of the dreaded syphilus. MGM assigned the project to Tod Browning, who was well versed in themes of this nature, although this was the only Chaney film that did not come from an original story of his. Browning did, however, contribute the prologue involving Phroso’s background as a stage magician. This was an element not in the play. Another element that certainly bears the imprint of its director is that of the con– working a crowd of suckers for a few coins. Author Michael Blake elaborates on material that was shot by Browning but which was eventually cut out of the version we know today:

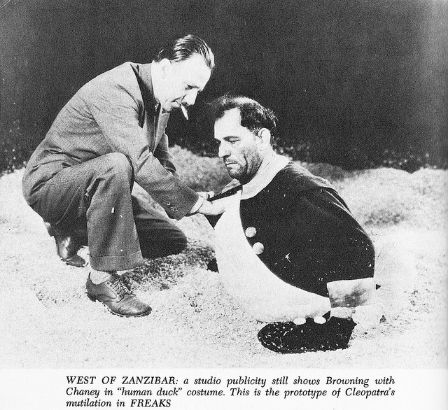

“One sequence in both the May 17 and June 7 drafts features a unique shot illustrating the travels of Chaney’s character in his attempt to find Crane. The camera, acting as Phroso’s eyes, showed various faces of French, Italian, Turkish, Arabic, and finally, African people pass by (the background in this shot was indistinguishable), indicating the various countries through which he passed on his search. When the Africans walk past the camera, the scene dissolved to the dive where Phroso comes in on his cart pleading for money. He is taunted by two men, Babe and Tiny, who throw him through the saloon’s window. This brutal act upsets the patrons of the bar, and Doc pleads for pity on behalf of Chaney’s character. The scene ends with money being thrown into a hat, and dissolves to Phroso, Doc, Babe, and Tiny counting the collected coins. This scene, along with the one with Chaney appearing as the ‘human duck,’ were actually filmed, but deleted from the final print.”

West of Zanzibar’s famous “lost scene” depicting Phroso working in a carnival pit show as “The Human Duck.”

As with their other films, West of Zanzibar deals with the forces of vengeance and Fate. It plays out like a great tragedy from literature. From the opening “Ashes to ashes, dust to dust” title card to its fiery conclusion, there is a unity and a keen design to the film that holds it together. Chaney biographer Michael Blake sees the ending as a weakness, that it seems rushed, but it contains one of the most compelling moments in the film. The final look between Phroso and Maizie is unforgettable.

West of Zanzibar is a film about primal instincts and cruelty and how these things can torment the soul. Phroso’s transformation into Dead Legs transpires not in civilized society, but rather in Africa which, at that time, was a place of mystery and danger in the popular imagination. There is an unwordly eeriness to the film which is certainly heightened by the existing prints with their many scratches. There is nothing quite like West of Zanzibar.

The production never actually left Culver City, but you’d never know it watching the film. MGM could realize the African environment like no other studio– thanks in part to underground steam pipes that made the backlot sufficiently humid. This sense of place fit the squalid atmosphere of the film where characters are lost in a moral limbo. In the years ahead, MGM would be responsible for such films as Trader Horn and the Tarzan series. Browning transformed the MGM lot into many exotic places for films like The Road to Mandalay and Where East is East, his tenth and final film with Chaney.

Mary Nolan, who plays Maizie in the film, was a former Ziegfeld Girl who performed under the name Imogene “Bubbles” Wilson. But a scandal with a married man ended her stage career; she had been the mistress of Broadway comedian Frank Tinney. In the wake of the affair, she travelled to Europe and made several films in Germany before returning to the United States in 1927. She was reportedly cast for the role in the MGM film due to her “tragic eyes.” By the early 1930s, however, Nolan’s film career was on the decline. She suffered from drug problems that hampered her career. She was only 45 when she died in 1948.

The role of the burnt-out doctor who attends to Dead Legs is played by Warner Baxter. He would go on to become a leading man in the 1930s in films like 42nd Street, Penthouse, and The Prisoner of Shark Island, which will be shown later in The Rediscovered (May 22). Shortly after making West of Zanzibar, Baxter won an Oscar for his performance as the Cisco Kid in In Old Arizona.

Lionel Barrymore was the elder brother of John Barrymore and a great talent in his own right. He became a popular star for MGM and appeared opposite many of the studio’s biggest stars. In 1931 he won the Oscar for Best Actor for A Free Soul. Shortly after appearing in West of Zanzibar he was nominated for an Academy Award– not for acting, but for directing 1929’s Madame X with Ruth Chatterton.

But the film belongs to Lon Chaney. Was there ever an actor with his sense of purpose? Every strength and flaw in a screen characterization is captured and heightened by Chaney. Everything revolves around his character. He is a vindictive force that pulls in those around. Dead Legs is like the crawling things seen in the African night, a creature fueled by revenge and mean-spiritedness, and yet, there is also a humanity that never seems forced or contrived. He is not a monster when we recall him as Phroso in the opening scenes. His interaction with his wife and the film’s tone convey a Victorian sensibility towards love and marriage. He is a man who loses a wife who is everything to him. He then snaps.

West of Zanzibar was a profitable venture for the studio–it made nearly $89,000 in its first week at the Capitol Theatre– but not everyone was happy about what was depicted on the screen, mainly the critics. The harshest review came from Harrison’s Reports:

“This piece of filth is the stage play Kongo. And upon this play the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer picture West of Zanzibar has been founded. How any normal person could have thought this horrible syphilitic play could have made an entertaining picture, even with Lon Chaney, who appears in gruesome and repulsive stories, is beyond comprehension.”

In the decades since, Tod Browning’s stature has been elevated by horror fans. His best films gave voice to the afflicted and the tormented. The films with Chaney were essentially horror dramas– precursors to the supernatural horror genre of the following decade. MGM was known primarily for their upscale productions– sophisticated dramas about the rich and young in modern times– so it was particularly refreshing that a director like Browning worked in this studio milieu. MGM was known for their legendary stars, yet within this polished machine, Tod Browning was an original who put his personal stamp on his pictures. They were some of the most interesting films that ever came out of MGM at that time. His themes and his imagery are once again ready to be rediscovered– this time in a library series that takes us off the beaten path.

I remember the excitement I had when I bought a VHS copy of West of Zanzibar at a movie convention some twenty years ago. There was a different music track than the one you hear on the Warner Archive release. I remember the sombre mood of seeing Chaney propelling himself on a wheeled platform down a street towards a huge city church. I could always recall the three old women gossiping about Phroso’s wife having returned to town, and then he finds her there in the church. It was a very powerful moment with the very haunting music, and it shows the importance of music for a silent movie.

For our presentation, we will be fortunate to have a live piano accompaniment by jazz musician David Drazin. He is one of the best silent film accompanists anywhere. David had performed for me previously at the LaSalle Bank Theatre. He played during a Veterans’ Day screening of Tell it to the Marines with Lon Chaney. It is always interesting to hear another musical interpretation.

West of Zanzibar has the prestige of being our Opener. It’s a very strange film, but we’re not your normal classic film program. It’s only 65 minutes, but it’s more mesmerizing than these bloated modern movies that rely on excess and subplots for two and a half hours. All that is gone here. What we do have is Lon Chaney. In our sixth season of playing movies at the Library, we thought our tribute to the man of a thousand faces was long overdue. He was a master of pantomime drama– the ne plus ultra of the silent screen. To those who are challenged by silent movies (or anything in black and white, for that matter), you have no idea what you’re missing.

* * * * * * * *

This entry was originally published in the movie blog The Rediscovered. For more information on these weekly film screenings, Click Here!

One thought

Comments are closed.