“Remember, as was once told me, ‘Life is to give, not to take.’” ~Fredric March as Jean Valjean in Les Miserables (1935)

In 2015, we look beyond the veil of our existence as we take a spiritual journey through the movies. Cinema of Transcendence is an original program that explores the role of spirituality and faith in classic Hollywood. When audiences think of the image of God on film, they might recall directors like Cecil B. DeMille, who was famous for the Bible stories he brought to the screen. Others might remember composers like Miklos Rozsa, whose musical scores brought a spiritual power to many epics from the 1950s.

In a modern age that is often cynical and skeptic, Cinema of Transcendence seeks to uplift and inspire with a positive image of religion. These films reflect the exalted virtues of love, forgiveness– and the kind of courage born in Heaven. They project a translation of God’s Word through a Hollywood perspective. If these films have historical shortcomings, they nevertheless remain faithful to the spirit of the Word.

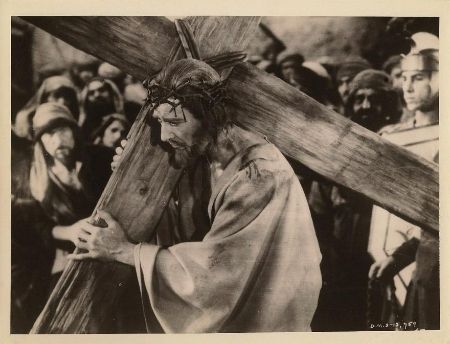

Movies inspired by the Holy Bible go back to the very early days of the silent cinema. At the turn of the 20th century, several short films depicted the passion play. The biggest commercial and artistic successes, though, were made by filmmakers like Cecil B. DeMille, whose 1927 version of The King of Kings remains one of the great triumphs of religious storytelling. DeMille also made the 1923 version of The Ten Commandments (a film he would remake in 1956.) Other directors with notable contributions to the subject include D.W. Griffith (Intolerance, 1916) and Fred Niblo (Ben-Hur, 1925). Michael Curtiz’s Noah’s Ark (1928) was a “part-talkie” disaster film produced by the Warner Bros. studio.

H.B. Warner as Jesus in the most reverent and beautiful screen version of Christ in DeMille’s The King of Kings (1927).

Films that touched upon the Divine were evident during Hollywood’s “pre-Code” era of the early 1930s when adult subjects were treated with a frankness that shocked the general public. The moral outrage of various civic and church organizations would force Hollywood’s Production Code to be enforced in 1934. But before that time, there were many films that mixed religion with vice. The Sign of the Cross (1932) is a notorious example of Cecil B. DeMille shocking his audiences with sexual imagery. But the sin depicted was in equal parts balanced with a powerful message about faith and pure love. Other pre-Code films of the era with spiritual themes and motifs include Safe in Hell (1931) and Gabriel Over the White House (1933).

Some of the best literary translations in the mid-1930s featured strong themes about redemption and noble sacrifice (A Tale of Two Cities, 1935) as well as forgiveness and charity (Les Miserables, 1935). Dante’s Inferno (1935) tells a modern day parable with a recreation of the Hell from Dante’s famous poem, The Divine Comedy. The nightmarish imagery from this largely overlooked film is an impressive achievement in art direction.

A vision of Hell from Dante’s Inferno (1935).

The Word of God has been told using legend (the Holy Grail in The Light in the Dark aka The Light of Faith, 1922), allegory, (The Passing of the Third Floor Back, 1935 (UK), Strange Cargo, 1940), history (Last Days of Pompeii, 1935, The Crusades, 1935, Joan of Arc, 1948), and through films dealing with visions and miracles (The Song of Bernadette, 1943).

Many films in the 1930s and 1940s offered positive images of church clergymen and priests. Spencer Tracy in Boys Town (1938) and Bing Crosby in Going My Way (1944) are just two of the many fine examples of how Hollywood defined the priesthood.

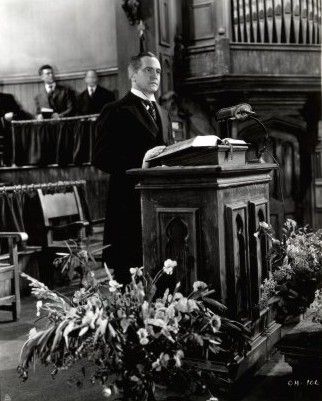

One of the most remarkable films of the 1940s is One Foot in Heaven (1941) starring Fredric March as a Methodist minister in early 20th century America. This is one of the most intelligent and uplifting family films from Hollywood’s golden age. One Foot In Heaven remains the primary source of inspiration for Cinema of Transcendence.

Fredric March in One Foot in Heaven (1941).

Other films that have glimpsed the eternal include Frank Capra’s Lost Horizon (1937), which sought an earthly transcendence for society itself. Though not an overtly religious film, Lost Horizon is one of the most soulful films to come out of Hollywood. The Razor’s Edge (1946) presented the main character of Larry Darrell (Tyrone Power) on a spiritual search for the meaning of life. These films and others have featured characters seeking a mental and spiritual transcendence. Society and the individual could reach beyond and become something far more than what we are now.

A subcategory of spirituality is a group of films that could be classified as angels and demons. Movies like The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941) and It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) featured strong religious elements even though the films themselves were not directly about religion. Several fantasy films offered a more playful take on religious concepts. Actor Claude Rains managed to play an angel in Here Comes Mr. Jordan (1941) and a devil in Angel on My Shoulder (1946).

Spirituality onscreen permeated many genres, from horror (The Bride of Frankenstein, 1935, and The Walking Dead, 1936) to Westerns like 1950’s Stars in My Crown. Actors one might not normally associate with religion appeared in some very unusual but remarkable films including Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. (The Gaucho, 1927), Boris Karloff (The Walking Dead, 1936), and even Errol Flynn in The Green Light (1937), a melodrama based on a novel by Lutheran minister Lloyd C. Douglas, author of Magnificent Obsession (1935).

But it was the 1950s that saw the greatest stories ever told on movie screens. Audiences could now witness the exodus of the Jews from Egypt and the birth of Jesus Christ not only in color– but in widescreen. In an effort to bring audiences back to theatres—and away from television—many new widescreen formats such as CinemaScope turned the movies into spectacles.

Charlton Heston as Moses in The Ten Commandments (1956).

Two of the most popular films from the 1950s are The Ten Commandments (1956) and Ben-Hur (1959). The Ten Commandments, DeMille’s final film, has become a television tradition with its perennial showing every Easter. The force of the film’s storytelling and the strength of its convictions have towered above every version made since. Ben-Hur, based on Lew Wallace’s 1880 novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, was a remake of the famous silent film and contains the most spectacular horse race in film history. Ben-Hur would also become the most honored Biblical epic with 11 Oscar wins.

Other important Christian films from the 1950s and 1960s include Quo Vadis (1951), The Robe (1953), The Big Fisherman (1959), King of Kings (1961), and The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965). Two of which, The Robe and The Big Fisherman, were the works of author Lloyd C. Douglas.

Throughout the history of religious cinema, there have been many that have challenged our beliefs and notions of holiness. Frank Capra’s The Miracle Woman (1931) features Barbara Stanwyck as a fake evangelist milking the multitudes. It also offers a powerful indictment of the hypocrisy that can be found in any local congregation. Night of the Hunter (1955), now recognized as a masterpiece in visual storytelling, presented a murderous preacher (Robert Mitchum) whose religious fanaticism is counterbalanced by the genuinely spiritual presence of Lillian Gish. These films as well as others like Elmer Gantry (1960) present a darker vision of faith based on the wayward motivations of its practitioners.

Films with religious themes continue to be popular to this day, even against the forces of modernity. However, most of these faith-based efforts are artistic failures. What Christian cinema markets today, both theatrically and on cable, is often condescending and simplistic. In addition, modern reinterpretations of the Bible– as well as satirical religious films– have only widened the gap between the reverence of the past and the irrelevant present. Nonetheless, the values and teachings of the Judeo-Christian faith have had great success manifesting more subtly in unlikely places. Themes of temptation and redemption– and an all-powerful guiding force– have surfaced in many genres, from children’s fantasy to popular science fiction.

Cinema of Transcendence is a series about discovery, revelation and, we hope… illumination.

Cinema of Transcendence runs from March 5 to June 4 at the Park Ridge Public Library. To learn more about the spring series and to see the complete schedule of films, please visit the official series blog: Cinema of Transcendence.