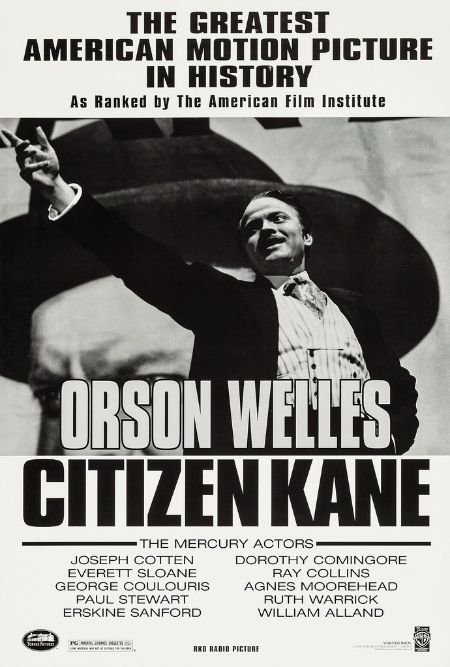

Citizen Kane turns 75 this year. Our anniversary screening at the Pickwick Theatre on February 11 would’ve been more timely had the film actually been released in February, 1941, as it was originally intended. However, due to the controversy surrounding William Randolph Hearst– the film’s primary inspiration who carried great clout in Hollywood– the original release date was delayed until May, 1941. (See the documentary The Battle Over Citizen Kane for more on this aspect of its history.)

Our screening celebrates the legacy of what is widely acknowledged as the greatest movie in American cinema. Much has been written of Citizen Kane, and most of it by scholars far more knowledgeable on the subject than I. Instead of simply repeating information you can find elsewhere, I thought I’d say a few words as to how I came to discover this classic. (For those who are interested in the film’s fascinating production, I would highly recommend reading The Making of Citizen Kane by Robert L. Carringer, 1996.)

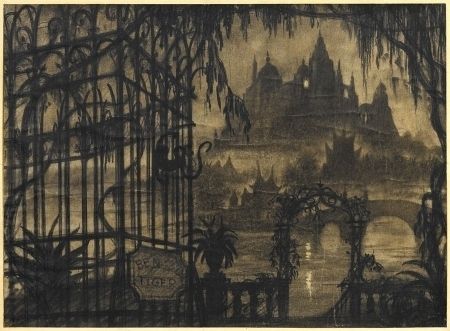

My respect for Citizen Kane came later in life when I was already out of my teens. In fact, I knew about William Randolph Hearst before I had ever seen Citizen Kane. I vividly recall a trip in 1993 when I visited the Pacific Coast and toured Hearst Castle at San Simeon, the model for Kane’s Xanadu home. At San Simeon, I was aware of the Hearst connection to the Orson Welles film, but that was about it. I don’t even recall seeing Citizen Kane at Columbia College, but I do remember a screening of Welles’ follow-up, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942).

My first distinct memory of Citizen Kane was at the LaSalle Bank Theatre near Six Corners in Chicago. At that time in my life, there were other films I ranked higher, but I concede that my “Greatest Film of All-Time”– 1933’s King Kong— is more of a personal “favorite.” My History of Cinema teacher did point out to me that a little part of my beloved Kong is, in fact, in Citizen Kane. If you look closely at the Everglades scene in which Charles and Susan are encamped, you can clearly see backscreen projection of “birds” flying in the jungle. I was told this was from King Kong; however, I believe it’s actually from Son of Kong. (Either way, it’s one of the few times Welles used rear projection in Kane, and this particular footage was already available to him in the RKO library.)

A charcoal sketch of Xanadu by the great RKO matte artist Mario Larrinaga.

When you grow up hearing repeatedly that such and such movie is the greatest, there is an inclination to go against the grain and seek alternatives, but all roads eventually lead back to Xanadu. That first theatrical screening at the LaSalle Theatre made an impression on me, instilling an appreciation that would grow in the years ahead with repeated viewings. The film is technically brilliant with an intricate storyline told in flashback chronicling the rise and fall of a newspaper tycoon.

Park Ridge Classic Film hopes to preserve the film’s standing in the public consciousness that this is the greatest movie of all time. With each generation, there is a tendency to look for something else as I had done, perhaps it’s a film with a level of expression that speaks more to that generation. In the 2012 Sight and Sound poll, Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) became the new Number One. Vertigo is Hitchcock’s masterpiece, a great film, but it’s not the groundbreaking film that Citizen Kane is. Fifty or a hundred years from now, will Kane even be in the Top 5? Look at the unfortunate fate of D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915)– a film once hailed as the greatest motion picture, and today it’s been relegated to screenings in art museums with historians speaking of its importance only in hushed tones. Of course, the nation’s shift in attitudes towards race and politics adversely affected The Birth of a Nation‘s standing. But how will succeeding generations view Kane— with reverence or boredom?

Citizen Kane is pure cinema, and its camera techniques broke all the rules in 1941. The film was shot by the best cameraman in the business, but will modern audiences really understand what went into those great visuals? Even in its day, Citizen Kane was not a popular film for the general audiences; it did not do well at the box office. Regardless of receipts, Orson Welles was a true visionary in every sense. Filmmakers should look to him and study his films because, unlike the mass mediocrity of filmmakers today, Welles didn’t rely on gimmicks, pixels, or noise. He was a great illusionist who elevated the medium with his artistry.

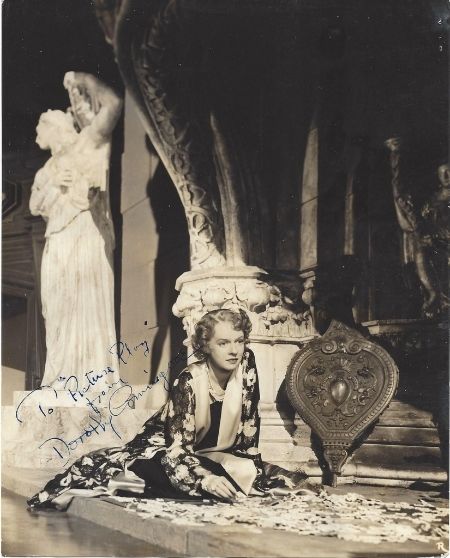

A controversial connection to Hearst: the Marion Davies-like character of Susan Alexander. In reality, Marion Davies was a more talented comedienne than Susan was a singer.

On the surface, the story of Charles Foster Kane would not appear to be “relevant” to a millennial. What was topical in 1941 is unfamiliar in 2015. How many young people even know who William Randolph Hearst was? But the point is that it doesn’t matter when you watch Citizen Kane. Irrespective of the movie’s character antecedents, Kane‘s themes remain relevant– its drama just as riveting. At its core, Kane is the story of a man whose idealistic fervor becomes as hardened as the cold statuary he collects around him, whose innocence is crushed by the pursuit of power and wealth– a “root of all evil” moral that can be traced back to passages in the Bible.

I’d like to see young people come out and enjoy the experience and appreciate the things that make the film unique. A lot has been said of Orson Welles producing the film at the age of 25, and that certainly is remarkable. It’s given young filmmakers hope that their celluloid dreams can materialize. But we should also realize that Welles knew nothing about making a Hollywood movie prior to arriving on the RKO lot. The greatness of Citizen Kane is that it was a collaborative process. Welles’ vision was the driving force, but without talents like cinematographer Gregg Toland or screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz or art director Perry Ferguson, Citizen Kane might never have gotten off the ground, or if it had, Welles might’ve floundered without those other talents helping him.

One of the misconceptions the general public has is that Orson Welles never made anything as good after Kane, that his last years were spent in exile from Hollywood making low-budget independent movies that never came close to the quality of his first movie. This is not the case, and this point will be discussed by our special guest, producer Michael Dawson. Mr. Dawson is a Chicago area filmmaker who has worked on the restorations of Othello (1952) and Chimes at Midnight (1966). He is an authority on the life of Orson Welles and he will be speaking onstage before the movie.

Citizen Kane screens this Thursday night at 7:30 PM. It will be presented in a stunning 4K digital restoration.

~M.C.H.