“It is Sergio Leone’s masterpiece, the one he was practicing for with those hard-edged Clint Eastwood Italian westerns Leone directed in the 1960s. More epic in scope and richer in storyline, Leone’s ace-card this time was his casting the all-American good fellow Henry Fonda as a vicious, evil, and morally corrupt killer. Fonda later said it was his favorite of all the screen roles he played.” ~Robert Osborne, 52 Must-See Movies and Why They Matter (TCM The Essentials)

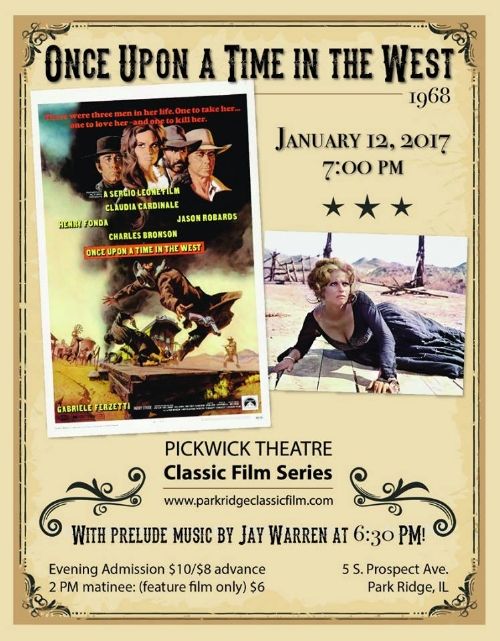

WHAT: Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) uncut version on DCP

WHEN: January 12, 2017 2pm & 7pm

WHERE: Pickwick Theatre, Park Ridge, IL

WHAT ELSE: Jay Warren performs pre-show music at 6:30pm

HOW MUCH: $10 ($8 advance)/$6 for 2pm matinee (feature film only)

Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) is his most-acclaimed movie. Not only is it considered the finest “spaghetti Western” ever made, it also appears on several “greatest movies” lists. Admittedly, it was a film I did not discover until recent years. My first introduction of it had been a clip of its opening sequence in a History of Cinema course at Columbia College. Being a fan of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966), I was perhaps biased and not as motivated in seeing OUATITW. After all, it didn’t star Clint Eastwood! I had a similar reaction to On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969) when I first watched it on network television as a kid; it didn’t star Sean Connery, so how could it be as good? But as you grow older and re-discover these films and see what makes them work– regardless of who has star billing– you appreciate the artistry that went into their production. Once Upon a Time in the West is indeed a great movie directed by a master storyteller and featuring an outstanding cast–yes, even without Clint Eastwood.

Leone was a director influenced by the great Hollywood Westerns, but rather than copying them, he turned convention upside-down, reinterpreted them, and developed his own operatic style. At the same time, he embraced and paid homage to the classics that had come before. Characteristic of Hollywood Westerns like Shane and My Darling Clementine, his Italian Westerns were mythic. Often, there was a mysterious stranger, a man of destiny, who was seemingly more “good” than bad. Through this character, Leone restored the mythic, Western hero, but around him was a much different universe than the West of John Ford. A Leone Western is unmistakable with his long shots of barren landscapes juxtaposed with extreme close-ups of characters. There was a grittiness to the movies that was perhaps truer to what the Old West might’ve been, but Leone was never interested in “realism.” He was more about the expression of style. If anything, his images were more influenced by Italian Surrealism. Even the sound design in a Leone film has an exaggerated quality that separates it from other films of the period. Leone’s films are unique unto themselves. Unlike a contemporary filmmaker like Sam Peckinpah, who fixated on the violent action itself, Leone was more preoccupied with the rituals of Western tradition and the ceremonial choreography of the duel. Around the gunplay were sequences drawn out and built up for maximum suspense. That was the Leone rhythm.

Henry Fonda’s first onscreen love scene… with Claudia Cardinale.

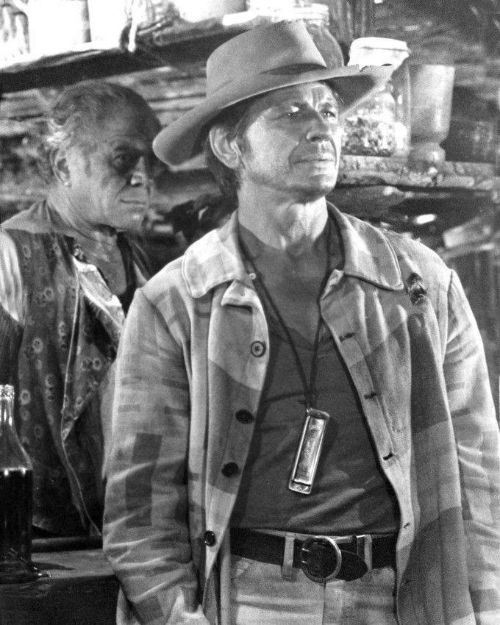

One of the exceptional examples of this rhythm is the opening scene of OUATITW in which three gunmen are waiting at a station for a train that is running late. It’s the reverse scenario of High Noon in which everyone is waiting for the villain to arrive. Here, it’s Bronson’s Harmonica who suddenly appears after the train has departed. With the opening, Leone has designed a ten-minute sequence with a very deliberate pace, yet viewers remember every detail and nuance that happens during the course of the scene. By the standards of today, if this were reshot for modern sensibilities, the action would be immediate and nonstop with ten minutes devoted to the action itself– meaningless images saturated in visual overload. That was never the case with Leone. An attentive viewer will remember how his shots are composed. Apparent in the shot composition is the influence of directors like John Ford. At the train station, for example, there is doorway backlighting– a shot of a dark interior looking out to a bright exterior– which recalls similar shots in The Searchers. There is an artistry to how scenes unfold and build suspense. This is further enhanced by what is heard. The opening has no music, and what we hear on the soundtrack are the natural sounds of the environment. These, too, we remember. We hear the rusty squeak of the windmill as it turns and the droplet of water as it hits the top of Woody Strode’s head. Throughout the film, Leone makes use of sounds that are unique, from gunshots to the wheezing sound of a train at rest.

How Leone introduces characters is done in such a way that their entrances (as well as their exits) are equally unforgettable. We remember Claudia Cardinale’s introduction as she steps down off a train in Flagstone. Certainly one of the most beautiful actresses to ever appear on-screen, the presence of Cardinale is a rather new element for a Leone film, which had always been male-dominated. However, the most striking entrance in the film is the moment when Henry Fonda’s cold-blooded Frank appears onscreen. The first image is one of him in a long shot with his men emerging from behind some dusty sagebrush. Then, as we see them from behind, the camera moves around to reveal that it is indeed Henry Fonda– an actor who had always played characters of integrity. Here, he is cast against type as one of cinema’s nastiest SOBs. Fonda was not only chosen for his acting ability, but for what he brought to the film from his other movies, particularly those he made with John Ford like Fort Apache and My Darling Clementine. In this film, Fonda brings a sense of history to the Leone production. It was nothing new to see an old-time American actor cast in a European Western, but there is something very rewarding in seeing an actor of Fonda’s stature– one we normally associate with the “golden era” of Hollywood– now reimagined in a “modern” Western.

Henry Fonda, who brought the John Ford iconography to a much different role.

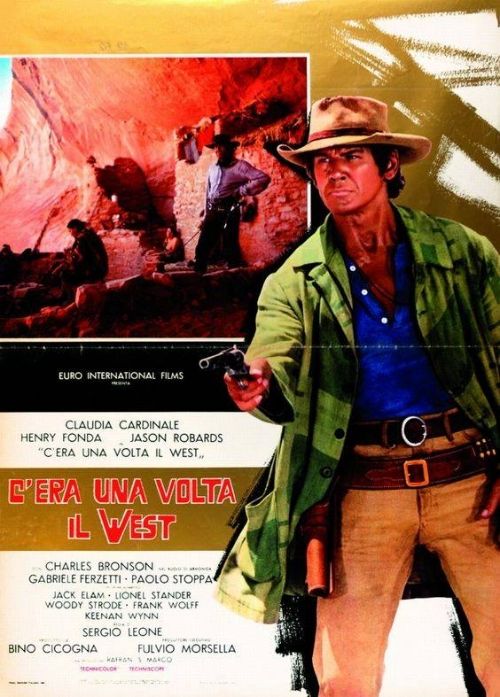

Once Upon a Time in the West also features Charles Bronson as the mysterious Harmonica (a role first offered to Clint Eastwood), Jason Robards as the outlaw Cheyenne, and Gabriele Ferzetti as Morton. It’s a who’s-who of familiar American faces that are recognizable to movie buffs: Woody Strode (another John Ford veteran), Jack Elam, Keenan Wynn, and Lionel Stander.

Written by Leone, Dario Argento and Bernardo Bertolucci (with the screenplay by Sergio Donati), the story chronicles several characters whose lives are intertwined with the building of the transcontinental railroad. It’s set in the early days of the rail line when the robber barons ruled the Old West. Morton is one of these unprincipled types, a crippled figure who uses gunmen to advance his dream of reaching the Pacific by rail. With the help of Frank (Fonda), Morton plans on removing any settlers who get in his way, such as the entire McBain family. One of whom is former prostitute-turned-widow Jill McBain (Cardinale), who has inherited a piece of land, Sweetwater, with a hidden value. Threatened by the gang, Jill plans to move on, but it’s the mysterious Harmonica, with his own motives, who convinces her to stay and develop the land. The “only at the point of death” sequence– between Harmonica and Frank– is one of the great moments in cinema and reminiscent of other duels from Leone’s Western’s.

OUATITW is an elegy to an era– the end of the gunslinger who here is being replaced by industrialization (the railroad) and community. Loners like Harmonica, Cheyenne and Frank no longer fit in the new West. They are classic Western archetypes who embody an era that is slipping away. In a larger sense, the film also represents the swan-song of the Western genre itself. Leone wanted to create a world that we were already familiar with. Throughout OUATITW there are references to other films, what Leone called “a kaleidoscopic view of all American Westerns put together… to use some of the conventions, devices and settings of the American western film, and a series of references to individual Westerns… to tell my version of the story of a birth of a nation.”

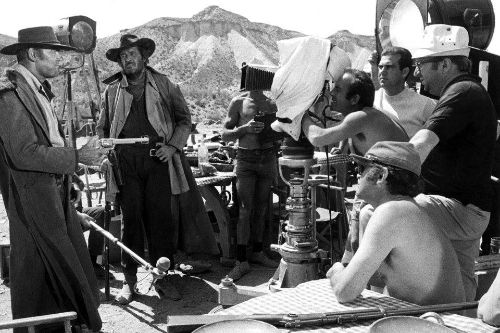

Ennio Morricone, whose music did much to shape and define the spaghetti Western, composed one of his most lyrical scores and gave the film an epic sense of grandeur. The main title, as well as compositions like “Jill’s America,” have the same majestic quality of themes like “Tara’s Theme” from Gone With the Wind. Morricone’s style in this film is very much reminiscent of the great Hollywood composers like Max Steiner. Besides its music, the film is remarkable for its cinematography. The film was gorgeously photographed by Tonino Delli Colli and shot in Italy (at Cinecitta Studios), in Spain, and– as fans of John Ford well know– Monument Valley in Arizona. Every composition in OUATITW is spectacular. It’s understandable how the film’s visuals are now studied in film school.

The film has influenced a generation of filmmakers, including the greatest living director, Martin Scorsese: “But what I found so fascinating, and how Once Upon a Time in the West became such a favorite film of mine– such an obsession– was that I began to understand more and more the combination of commedia dell’arte with operatic tradition and the framing; the framing, which was not simply comic-book art– which is very strong and very visual, it’s very cinematic– but also baroque art, the faces of the characters like landscapes, explored in close-ups and in even tighter close-ups, extreme close-ups; the extraordinary manipulation of the editing, slowing down time– first in the opening sequence of Once Upon a Time in the West before the titles– slowing down time or accelerating time; and the choreography of Ennio Morricone’s music was the overall cue. I began to understand that this is opera, this is commedia dell’arte, this is Italian, it’s not an American Western. this is an evolution of the Western– this is a whole new genre and that’s what made it so important…” ~ quoted in Once Upon a Time in Italy (2005) by Christopher Frayling

Since first announcing it last January (when we presented a 50th anniversary of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly), no film has received more audience applause (at the mere mention of its title) than Once Upon a Time in the West. We will be presenting the uncut, 165-minute version. This screening is not to be missed –under any circumstances.

~MCH