The following is a transcript of my presentation on In a Lonely Place at the Park Ridge Public Library on May 11, 2017.

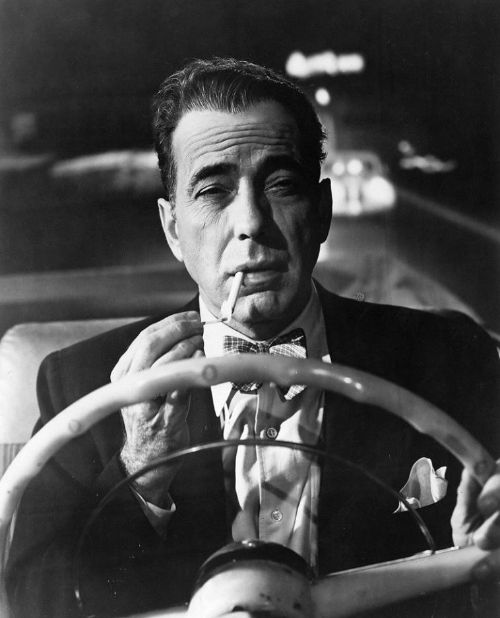

“I was born when she kissed me. I died when she left me. I lived a few weeks when she loved me.” ~ Dixon Steele (Humphrey Bogart)

In a Lonely Place (1950) is a movie about violence. The opening titles, set to the brooding music of George Antheil, is a sequence that stood out to me the first time I saw it in a college film noir class. Humphrey Bogart is driving through the dark streets of Los Angeles and we, the audience, see his eyes in the rear-view mirror as he looks straight ahead. As we’ll see later, the image has significance. This is a man whose past is in his rear-view mirror. That violent past is something he will not be able to leave behind.

Much has been written over the years about In a Lonely Place. The film has developed a lofty reputation and is now recognized as one of the great film noirs of the era. But is this high praise warranted? Absolutely. After all, there is a reason why every film noir publication revisits the film, and why today it has a 97% fresh approval rating on the web site “Rotten Tomatoes.” The film works because of its story and its acting. The role of Dixon Steele is often cited as one of Humphrey Bogart’s finest performances.

As Dixon Steele, Bogart is a Hollywood screenwriter with anger issues who is suspected of murder– but did he really do it? Gloria Grahame is Laurel Gray, his neighbor from across the courtyard who is the only witness to his innocence– but is she alibiing him only because she loves him? These questions are immaterial to what makes the film remarkable. The murder “mystery” is almost irrelevant. Instead, this is a story about how a murder impacts the lives of the characters. These relationships and the emotions they generate are more important than the detective plot. In Movies About the Movies, author Christopher Ames writes, “It appears to be a murder mystery, and yet the solving of the mystery becomes increasingly inconsequential.”

In a Lonely Place was based on a 1947 crime novel of the same name by Dorothy B. Hughes. Some fans of the novel might take issue with the screen adaptation, but the book was about a serial killer, and that wasn’t going to work onscreen in the 1950s. The main character in the novel was guilty and there was no mystery about it. In 1950, the censors in the Breen Office would never have permitted this storyline without significant revisions. Interestingly, the first story treatment, an adaptation by Edmund North, was supposedly more faithful to the source material. At this point in time, the producer had actor John Derek in mind for the role of the killer. Derek, who was then in his mid-twenties, would’ve been closer in age to the character in the book. However, once Bogart became involved in the project, the storyline was changed.

In the book, Dix poses as a novelist while committing heinous crimes, but in the film version, he has become a Hollywood screenwriter. There were many changes, and in the process, screenwriter Andrew Solt and director Nicholas Ray molded the story into something more meaningful than a B-movie crime thriller. Instead of focusing on the violence of a serial killer, Nicholas Ray was more interested in showing the violence that any man is capable of committing. In a Lonely Place presents us with the effects of that violence on a woman and how it impacts her relationship with the man she loves. She has a voice in the film and refuses to accept the violence in Dixon. Although we see things from Bogart’s vantage point throughout most of the film, we also identify with Laurel. Dixon is a possessive and controlling figure, and the menace that he projects is keenly felt by Laurel as well as by the viewer. Anyone who has ever been victimized by domestic abuse can certainly understand the mindset of Laurel. The depth with which this is conveyed onscreen makes In a Lonely Place a woman’s picture. Certainly, the way the film dramatizes domestic violence is exceptional for its era.

Though we never see the inside of a movie studio, the film goes behind the romantic illusions of the silver screen. Writer Imogen Sara Smith, in an astute essay for the Criterion dvd release, writes, “In a Lonely Place savagely sketches the vulgarity and shallowness of Tinseltown—the autograph hunters, the crassly arrogant stars, the vacuous audience and the moneymen eager to feed its appetite. But what makes this a heartbreaking tragedy instead of a jaded satire is that, beneath its bruised pessimism, the film still clings to the hope that art and integrity and love can survive in the wasteland—a hope that dies slowly, agonizingly before our eyes.”

In a Lonely Place is one of the most intelligent movies about Hollywood in its self-analysis. We see a writer struggling for artistic expression and seeking some validity in his work—and there is the washed-up actor finding solace at the bottom of a glass. In place of a soundstage, we have the Hollywood watering hole—here, a place called “Paul’s.” And like other films in this sub-genre, In a Lonely Place blurs the lines between movies and real-life. Bogart’s character looks at life as though it were a script. Like Sunset Boulevard and All About Eve—two other 1950 releases—In a Lonely Place reflects the delusions of show business.

Humphrey Bogart plays Dix as a brooding outsider who lives in a lonely place—a place without love. He is both a man of intellect and a man of violence. This is the primary conflict in Dixon Steele. But there is another antagonism; he is torn between being an artist and what he refers to as a “popcorn salesman.” Dix looks down on those who embody pop culture and he rebels against the constraints of mainstream picture-making—as represented by the formulaic novel the wide-eyed hat-check girl summarizes for him in his apartment. The best-seller he has been assigned to adapt is called “Althea Bruce,” a cliché-ridden product of mass culture. Despite this artistic handicap, he will turn the book into something more. This is ironic considering that Nicholas Ray himself was taking a novel and turning it into something more than a crime story. In the movie, Dix is told to “just do the book,” and in real-life, the filmmakers did the opposite.

Bogart made several notable appearances in “Movies About Movies.” Besides being a screenwriter in tonight’s film, he was a producer in Stand-In and a director in The Barefoot Contessa. The star was later dismissive towards In a Lonely Place, but this was most likely because it didn’t impress fans or critics. At the time, this was the measuring stick—not any artistic pretensions. The film may also have hit too close to home for him. Actress Louise Brooks once commented that Humphrey Bogart’s character in this movie came closest to the real man. Bogart supposedly had a temper with outbursts not unlike those of Dixon Steele.

Gloria Grahame plays a character who isn’t “coy, cute or corny,” but rather mysterious and frank. Throughout the 1940s, Grahame was often cast in secondary roles as the femme fatale, but In a Lonely Place, she stands out as the lead. Bogart had wanted Lauren Bacall, naturally, but Warner Brothers was unwilling to loan her out, and the head of Columbia Studios wanted Ginger Rogers. But Nicholas Ray believed Gloria Grahame was better suited to the role and prevailed in the end. It helped that she was married to Ray at the time. Laurel Gray is a character drawn to the very qualities in Dix that will ultimately drive her away. The man she loves is both creative and destructive with an element of danger that is mostly held in check. Dixon’s agent tries to justify this by telling her it’s a part of who he is– and she just has to accept it. He is still to be admired despite his flaws— “you knew he was dynamite,” he tells her. The movie shows her wondering, questioning, and doubting, and as a result, Ray eventually shifts our sympathies to her as she looks for a way out. We sense that this will be the last chance at love for both of them. The love that had united them has now brought out the weaknesses in each.

Nicholas Ray was a born outsider and could relate to the character Bogart was playing. Ray is best known today for directing Rebel Without a Cause, but his best work can be found in his film noirs like They Live By Night and On Dangerous Ground. Many of the characters in these movies wrestle with inner demons. In a Lonely Place is no different. Ray had worked with Bogart previously on Knock On Any Door, which was another independent film made under Bogart’s Santana Productions. Bogart felt he could trust Ray’s judgment and so had him direct this film. To his credit, Nicholas Ray re-shot the ending of the film when he felt it didn’t feel right. The resolution was originally much different. Ray believed everything in the script ended a little too neatly, so he and Bogart and Grahame improvised a new finish. It might not be the “great surprise” that the publicity department was trying to sell, but it’s an adult ending. It makes sense and doesn’t strike the viewer as being a Hollywood cliché—the kind that Dixon Steele would’ve hated.

In a Lonely Place is a film noir like others Nicholas Ray had directed, and some will argue it’s his best. There are the typical elements one associates with the style– the tortured protagonist, the police investigation– but the most noirish shot in the film comes when Dixon is recreating a murder scene. A key light shines across Bogart’s eyes as he directs a young married couple who sit by their kitchen table. He appears to be relishing the chance to see them act out a murder. In the scene, he instructs his old war-time buddy on the proper way of choking a woman in the front seat of a moving car. There is a fine line between normalcy and mania, and here Bogart’s character seems to suggest that anyone is capable of violence.

In a Lonely Place was made at a very paranoid time in Hollywood. This was the era of McCarthyism in which the government attempted to root out suspected Communists within the movie industry. It was a time of betrayal and suspicion, and Ray’s film taps into this sense of anxiety. Although the storyline has nothing to do with Communists, Ray captures a similar mood. The film was made at a time in Hollywood when many people were living on edge. Someone could be guilty by association, and it’s this sense of mistrust that surrounds Dixon Steele’s world. It is interesting to note that Art Smith, the actor who plays Bogart’s long-suffering agent, was soon blacklisted in Hollywood. The Chicago-born actor appeared in several notable films throughout the 1940s including Ride the Pink Horse—a movie that was also based on a Dorothy B. Hughes novel.

Additionally, film historians have drawn a parallel between the characters in the film and Nicholas’s Ray’s own personal life and his disintegrating marriage. Ray had married Gloria Grahame in 1948, but by 1950 they had separated—a fact they were able to hide from the cast and crew during the making of the film. The two would eventually divorce in 1952 after a rather tawdry incident involving Grahame and Ray’s 13-year-old son from his first marriage. Another connection to Ray’s own life is the film’s setting. The garden apartment where most of the film is set is based on the West Hollywood apartment Ray had lived in when he first moved to Los Angeles. Here, it’s been reproduced on a Columbia soundstage.

In a Lonely Place is a story about doomed love that resists the typical, romantic formula. A great example of this is the grapefruit scene in which Bogart’s character prepares breakfast for Laurel. From his perspective, it’s a domestic scene of bliss– like two people in love in a movie– but from her vantage point, this scene has a much different meaning. There is nothing conventional about their Hollywood romance. There is a fine line between love and physical threat. An arm around your lover’s neck can just as easily become a death-grip. This sense of unease and unpredictability hangs over the film and is magnificently acted out by Bogart and Grahame.

~MCH