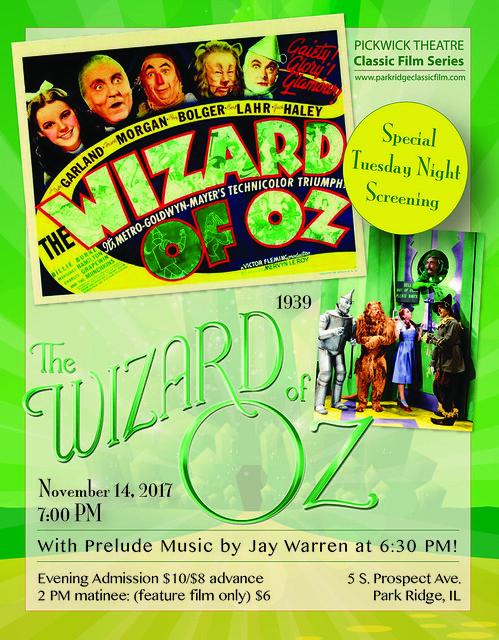

WHAT: The Wizard of Oz (1939) presented on DCP

WHEN: November 14, 2017 2 PM & 7 PM

WHERE: Pickwick Theatre, Park Ridge, IL

WHAT ELSE: Organist Jay Warren performs prelude music at 6:30 PM/cartoon

HOW MUCH: $10 ($8 advance before Tuesday)/$6 matinee (feature film only)

“It now seems probable that the particular achievement, the emotional strength and longevity, and the peaceful power and resonant magic of MGM’s The Wizard of Oz will never be equaled, and if it’s indeed true as the Wizard says, that a heart is not judged by how much one loves but by how much one is loved by others, then it’s very safe to say that the heart of The Wizard of Oz has indeed made it the best loved motion picture of them all.” ~John Fricke, Wizard of Oz historian

It was one of forty-one movies that MGM released in 1939. For those involved in making it, “Production 1060” was just another movie. But over the years, it’s been recognized as one of the greatest American movies. On November 14, 2017, the Yellow Brick Road will lead into the Pickwick Theatre as we proudly present The Wizard of Oz (1939). This is a film I’ve wanted to screen for many years, so on a personal note, I am excited to have this one on the program. The Wizard of Oz is part of our national heritage– part of our vocabulary– and given its impact on our culture, it’s something more than just another movie.

Like so many kids, my first experience with the film came in seeing it broadcast on network television. In my house, this was an annual tradition. I knew that every year around Thanksgiving I’d be watching The Wizard of Oz on CBS. (It was only during its 50th anniversary in 1989 that I finally saw it in a theatre.) Unlike today where you can watch movies any time you want– on demand– back then it was special because you knew millions of others were also watching it at that same time. It was always a big deal. Unlike the yearly showing of The Ten Commandments— a TV tradition that usually lasted over four hours– I would never miss one minute of The Wizard of Oz. It always seemed that Thanksgiving was the perfect time to show a film whose theme was there’s no place like home. That is what the holiday is about, being at home with family. And so, all these years later, I’m bringing a piece of my childhood– and undoubtedly yours– to the big screen. To keep the tradition, we’re presenting it a week before Thanksgiving.

This post is not intended to be an all-inclusive examination of the film’s production history. If the reader wishes to know how the filmmakers created the tornado effect or what became of the most famous costume piece in movie history– Dorothy’s ruby red slippers– I recommend reading The Making of The Wizard of Oz by Aljean Harmetz. This is a fascinating and detailed account of the film featuring interviews with primary sources. After the book was published in 1977, the author went on to revise it for the film’s “60th Anniversary” and, more recently, its “75th Anniversary.” A brief history of the film is in order, but rather than recycling points other authors have elaborated on, I will simply mention a few of the things that have stood out for me. (For those interested in Oz trivia, click here!)

The Wizard of Oz is a timeless motion picture with a continual charm. It takes us back to our childhood– not just our experience in watching it– and reflects our dreams when we wished for something better over the rainbow. Even as adults some of us still yearn for an escape from harsh reality. The film that gave us “dreams that we dare to dream” was based on the first of L. Frank Baum’s fourteen “Oz” books, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, published in 1900. Baum’s series was very popular, and he would return to Oz many times in the years leading up to his death in 1919. The story of a small Kansas girl named Dorothy who gets carried away by a tornado to the land of Oz resonated in children. Perhaps the success of the books could be found in the fact that they were written from the vantage point of a child, and they reflected how a child might think. The popularity of the books inspired the famous author to translate them to the movie screen. In the early days of silent movies, Baum produced three films which remain interesting curios today. The first Wizard of Oz movie came out in 1910. All of these are available on dvd. In 1925, Larry Semon directed an unsuccessful version of The Wizard of Oz which featured Oliver Hardy as the Tin Man. A more interesting depiction of Oz came in 1933 with a cartoon based on the book. This animated short was the first visualization to depict Kansas in black and white and Oz in color.

It was Walt Disney who indirectly brought The Wizard of Oz story back to movie screens. The success of his Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs* in 1937 inspired MGM to purchase the L. Frank Baum book. Snow White had been an animated movie, and at that time there was still some doubt in Hollywood whether a live-action fantasy film could succeed at the box office. Paramount’s Alice in Wonderland in 1933 had been a box office failure. It was producer Mervyn LeRoy– Louis B. Mayer’s replacement for the late Irving Thalberg– who wanted to make a film version of Baum’s book. Originally, he wanted to direct, but Mayer believed it would be too much responsibility for one man, so he gave LeRoy an assistant producer– songwriter Arthur Freed. (It should be pointed out that some accounts claim it was actually Freed who wanted to bring The Wizard of Oz to the screen as a musical.) Taking a pay cut to apprentice as producer, Freed was directly responsible for bringing in the songwriting team of E. Y. Harburg and Harold Arlen.

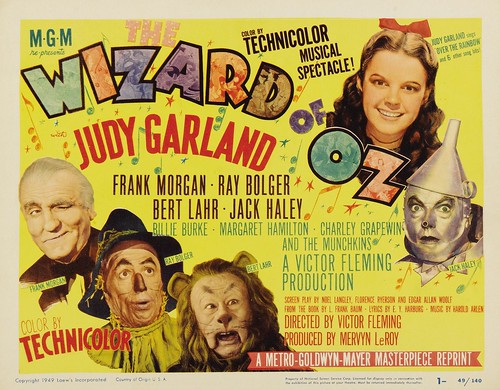

The Wizard of Oz is one of the great screen musicals, although we don’t always think of it primarily as a musical. What is unique about the film is that it was one of only a few at the time that used song to advance the story. Numbers like “Over the Rainbow” and “If I Only Had a… ” define character and serve as guideposts for the story. Most musicals at that time simply shoehorned a musical number into the scenario, as was the case in most backstage musicals of the era. Throughout the film, the lyrics reflect a playful use of language with songs done in rhyme, particularly in Dorothy’s introduction to Munchkinland. Additionally, there are variations of melodies dramatically heightened by Herbert Stothart, who composed the joyful score and won an Oscar for it– the one category where it beat out Gone With the Wind! Lyricist E. Y. Harburg and composer Harold Arlen created music that is instantly recognizable and which we identify completely with this film. No matter who else might sing “Over the Rainbow,” it will forever be associated with Judy Garland.

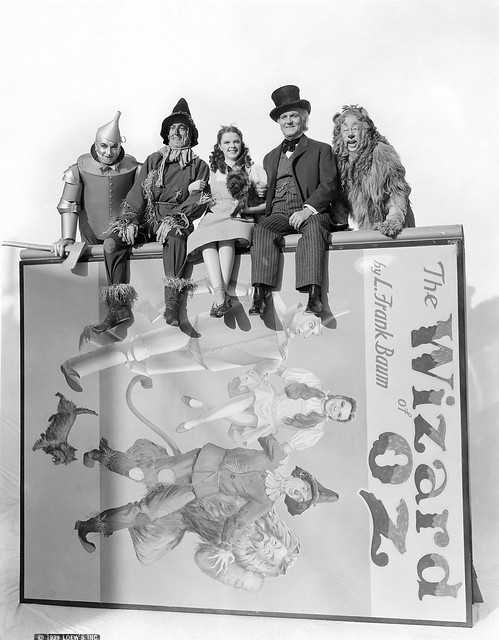

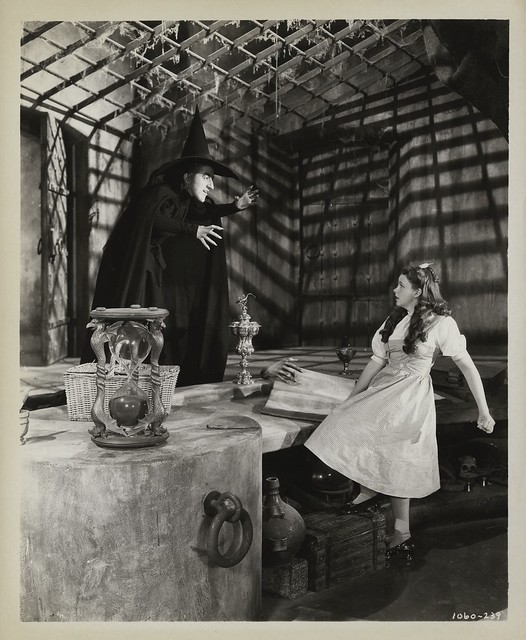

Judy Garland was fifteen years old when she was first cast to play Dorothy Gale. There had been some interest in borrowing Shirley Temple from 20th Century Fox for the part; however, Temple did not have Garland’s singing range. This would be a break-out role for Garland after being featured in earlier MGM films like Love Finds Andy Hardy with Mickey Rooney. Ray Bolger, one of the best song and dance men in Hollywood, was cast as the Tin Man and Buddy Ebsen as the Scarecrow, but Bolger believed he was miscast and wisely protested. Fortunately, Ebsen was willing to switch parts with him. Broadway star Bert Lahr became the Cowardly Lion, and Margaret Hamilton seemed born to play the Wicked Witch. (However, before Hamilton was brought onboard, LeRoy had experimented with the idea of casting a glamorous witch with actress Gale Sondergaard.) Frank Morgan brought his great versatility as a character actor to the picture and played five roles including that of the wizard. Richard Thorpe was hired as director, but he was essentially fired when his footage proved unacceptable to Mervyn LeRoy. Then, nine days into production, Buddy Ebsen had an allergic reaction to the aluminum dust make-up. His condition became serious, and although he would make a full recovery, he would not return as the Tin Man. Instead, LeRoy borrowed Jack Haley from 20th Century Fox. With the cast now in place, Garland would be working with three talented ex-vaudevillians as her co-stars.

The Wizard of Oz features a cast that seemed destined for the roles they played. Ray Bolger was the perfect Scarecrow. And although his solo number, “If I Only Had a Brain,” was shortened due to time, you can find the complete sequence as a “deleted scene” on the dvd. It’s a remarkable piece of choreography (staged by Busby Berkeley) well worth seeing as it was originally conceived. Additionally, an audio track survives of Buddy Ebsen singing “If I Only Had a Heart,” but Jack Haley’s version in the movie in clearly superior. Bert Lahr, on the other hand, was never completely happy with his performance when he saw it in later years; however, he was almost satisfied with his “If I Were King of the Forest.” This is an outstanding solo number, and his delivery and pronunciation of the words are what put the song over.

Though Dorothy was the main character, her companions on the Yellow Brick Road were pivotal. They give the story so much of its heart, and we recognize the humanity in these three characters who are not supposed to be “human.” When the Disney Studio made a sequel in 1985 called Return to Oz, there were some terrific things about it in terms of its visual design with characters like Tik-Tok, but what we missed were the human characteristics of Dorothy’s friends who, in the sequel, were merely animated costumes. The tears that Jack Haley’s Tin Woodman or Bert Lahr’s Cowardly Lion shed are nowhere to be found in the re-imagined Oz.

It’s hard to imagine anyone else in these roles, although there were a couple actors in Hollywood who might’ve come close. Though they were never considered by MGM, the role of The Scarecrow could have revitalized Buster Keaton’s career, and Three Stooges fans like myself could picture Curly Howard frightfully patting his brow with a handkerchief as Zeke and roaring as the Cowardly Lion. Though Shirley Temple was a (very brief) possibility after MGM acquired the rights to the book, the film would’ve failed with her in the lead. Although there were other young starlets in Hollywood like Deanna Durbin, no one had the singing range or acting talent of Judy Garland. It is her sincerity in the role that holds the entire picture together. Perhaps part of what draws us back to the film is seeing Judy Garland, the doomed star we remember from the 1950s, restored to what she had once been in her teens. The innocence that we see onscreen and the purity of her motives are far removed from the tragic figure who ended her life on the wrong side of the rainbow.

After some uncredited advice from director George Cukor (who shaped Judy’s Dorothy into more of a simple girl from Kansas), LeRoy hired Victor Fleming, who was adept at directing tough guy leading men like Clark Gable and Spencer Tracy. However, Fleming sincerely wanted to make a children’s film for his two daughters and brought the lighter touch that LeRoy sought. Fleming would work on most of the film, but eventually he was called away to direct Gone With the Wind. At that point, LeRoy brought in King Vidor to put the finishing touches on The Wizard of Oz. It would be Vidor who would shoot the opening scene in Kansas as well as Garland’s “Over the Rainbow” musical number.

What is remarkable is how well the film turned out despite having four directors working on it– and fourteen writers! The credited screenwriters were Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson, and Edgar Allan Woolf. In The Making of The Wizard of Oz, Aljean Harmetz goes through all the various writers and discusses what each contributed. The screenplay evolved over time and was not the product of one man’s vision, although Langley did the most to shape the story into the version we all know. Nor does the film carry the personal stamp of any one director. This was the studio era of filmmaking and it was a team effort– from the producers down to the wardrobe and props department. At MGM, directors had even less control and were, as was the case in The Wizard of Oz, interchangeable. The Wizard of Oz is a perfect example of the studio system at its height. Harmetz’s book details the layers of production and captures that era in Hollywood.

The Wizard of Oz is visually one of the most remarkable films of the 1930s. It was one of the big Technicolor productions of the day. The Kansas scenes were in black and white (given a sepia tinge), and then after Dorothy’s home drops from the sky, the door opened into the vibrant, colorful world of Munchkinland. Color is such a key factor to the success of the film. We can’t imagine it without seeing Dorothy’s red slippers, or the Yellow Brick Road, or the green face of Margaret Hamilton’s Wicked Witch. We are literally transported to another world. In addition to the color design, the visual effects represent the best studio filmmaking had to offer. Essential to the film’s success are the special effects by Arnold Gillespie. Long before computers created new worlds in pixels, Gillespie and his team worked in unchartered territory and were forced to innovate. Whether it was the famous tornado, or the flying monkeys, or the Wicked Witch skywriting “Surrender Dorothy” while riding her broom, the effects were essential components in bringing Baum’s imaginative story to the big screen.

Due to its high production costs, The Wizard of Oz did not make its money back on its initial release. It would not be until 1949 with its first re-issue that the film would near the break-even point. In the ensuing decades, when Oz‘s rights were sold to television, it would finally make a profit. Starting in 1956 with its first television broadcast, the film’s influence was felt on a new generation. The Baby Boomers grew up watching it on television, and then their kids followed suit. In 2017, The Wizard of Oz is considered the most seen movie in the world. It’s inspired fan clubs, countless merchandise and collectibles, and even a long-running Broadway musical called Wicked.

As we near The Wizard of Oz‘s 80th anniversary, it remains perhaps the most popular movie ever made. Various forms of media make the film available to younger generations, but nothing can take the place of a theatrical screening where you can see it with people around you and feel how the emotions of the film affect that audience. Some laugh with the characters and some applaud, and though we are in a darkened theatre, we know there are others there with us crying when Toto escapes the Witch’s castle or when Dorothy must say goodbye to her friends of Oz. Of course, we can experience all this at home, too, but there is something about the communal experience of seeing a film with a group that heightens those emotions.

What makes this film so special after so many years? The Wizard of Oz is both a sepia-tinged memory of middle America and a beautifully rendered fairy tale (in Technicolor) combining the best of the theatrical and cinematic art forms. Aside from its production values and technical marvels, I think there are several more reasons. No other film so poignantly captures the essence of the dream, of waking to something that had felt so real and wonderful. Of course, in the L. Frank Baum universe Oz was a real place– the filmmakers turned it into a dream. Purists might complain, but MGM made it an asset. It was so special because it contained the essence of the dream world.

Lastly, The Wizard of Oz takes us back to the innocence of childhood, when we looked at the world with wonder and dreamed of romantic places. And when we thought we couldn’t do something, all we had to do was look within. Dorothy helps her friends find qualities they always had inside them. That resonates as does the film’s theme: there’s no place like home. We live in a more cynical time that views sentimentality as a flaw and tries to tear down those values, but The Wizard of Oz restores our faith in them. Like the magical slippers, the film has the power to make us believe and hope, and it’s a reminder to be grateful for the people we have around us. When things are as they should be, home is what matters.

~MCH

*Adriana Caselotti, the voice of Snow White, was also in The Wizard of Oz. She played the part of “Juliet” in the Tin Man’s song, “If I Only Had a Heart.”