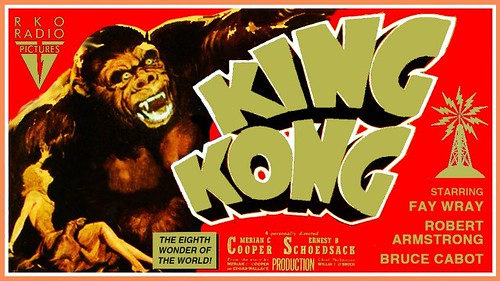

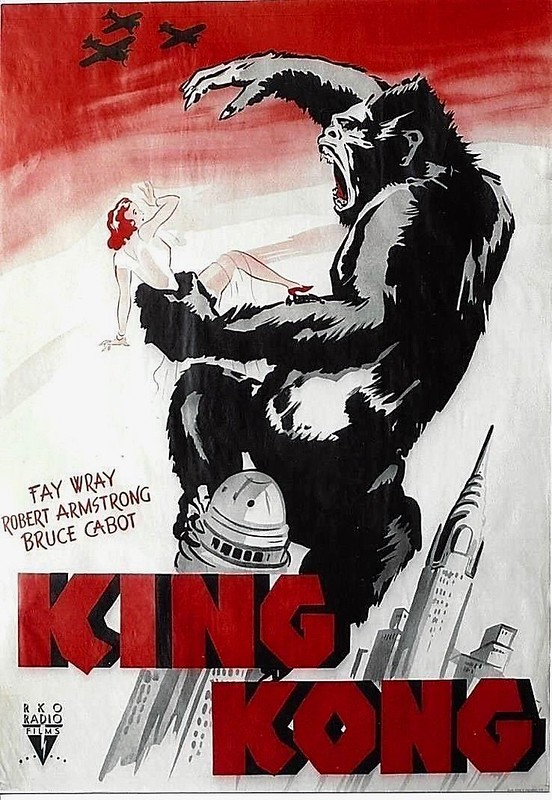

WHAT: King Kong (1933) 85th anniversary screening (DCP restoration, 100 min.)

WHEN: March 15, 2018 2 PM & 7:30 PM

WHERE: Pickwick Theatre, Park Ridge, IL

WHAT ELSE: Jay Warren performs prelude music beginning at 7 PM.

Steve Darnall, host of radio’s “Those Were the Days,” will be our guest in the lobby.

There will be King Kong memorabilia in the lobby including a replica of the famous Kong armature.

The first 500 patrons will be given a souvenir program featuring a special introduction by film historian Rudy Behlmer. Also, a cartoon before the feature.

HOW MUCH: $10/$8 advance (before the day of the show) or $6 for the 2 PM matinee (feature film only)

Advance tickets for the evening screening can be purchased Here!

Generations have grown up knowing the name King Kong. To the monster kids who came along in his wake, Kong is like an old friend who has always been with us. The story of a giant ape who climbs the Empire State Building has become something more than just an iconic image from an old movie; it’s a distinctly American fairy tale built around the theme of Beauty and the Beast. Over the last eighty-five years, the tale has been re-told and re-interpreted, but these versions are only louder with an almost total emphasis on special effects. Nothing has equaled the mythic proportions of the 1933 film. King Kong remains the greatest creature feature of all time.

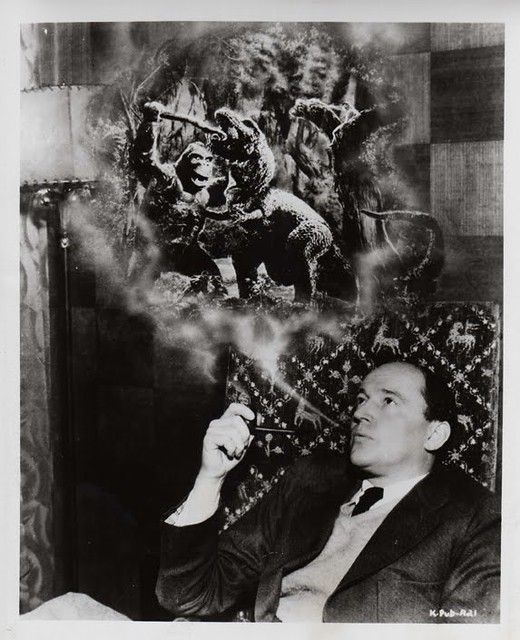

The story of King Kong was conceived by Merian C. Cooper, an adventurer who would leave an imprint on Hollywood larger than Kong’s own footprint on Skull Island. Cooper was born into a well-off Southern home in Jacksonville, Florida. The family had a long military history that would inspire Cooper to go off into the Army and later, become an airman. Beyond the stories connected to his Southern heritage, he was influenced by romantic tales of far-off lands. As a youth, Cooper was fascinated by exotic places. His imagination was stimulated when an uncle presented him with a copy of Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa by the French explorer Paul Du Chaillu. Tales of marauding gorillas fascinated him as a small boy, and it planted a seed that would flourish in the years to come.

Merian C. Cooper, the visionary showman behind King Kong’s creation.

Merian Cooper would go on to become a prisoner of war and a decorated soldier during World War I. In the aftermath of that conflict, he volunteered his services for Poland and helped form the Kosciuszko Squadron, a flying unit that fought the Bolsheviks during the Polish-Soviet War of 1920. Throughout the 1920s, he turned his attention to exploration and filmmaking. His friend and partner was Ernest B. Schoedsack, whom he had met in Europe after the war. Together, they shot Grass (1924), an ethnographic travelogue about the migration of a Persian tribe. Later, in Siam (modern-day Thailand), they made Chang (1927), a “natural drama” that followed the lives of a family of villagers as they survived the various terrors of the jungle. There were no gorillas, but rather big cats and a stampede of elephants—the chang of the title. As a result of their success, Cooper & Schoedsack were hired by Paramount to bring A.E.W. Mason’s The Four Feathers (1929) to the screen– their first trek into Hollywood territory. Shot on location in Africa, the film represented their leap into mainstream, fictional storytelling.

However, studio interference on The Four Feathers left a sour taste and steered Cooper away from the movie business. It is at this period in his life when he returned to his interests in commercial aviation and served on the board at Pan American Airways. Cooper was in New York at this time when the Empire State Building was being erected. The sight made a strong impression, and it was at that point when he began devoting more time to an idea he had for a gorilla picture. When David O. Selznick took over at RKO Pictures as the production chief in 1931, he invited Cooper to join him as his executive assistant with the freedom to produce his own films. The two had known each other at Paramount. RKO was one of the “Big Five” studios in Hollywood. Cooper knew this would be the time to bring his brainchild to the screen.

Merian C. Cooper was the inspiration for filmmaker Carl Denham.

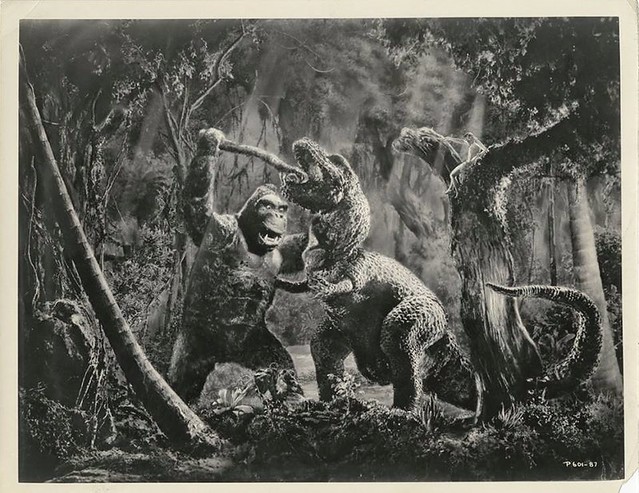

The genesis of Kong evolved over time. Originally, Cooper had imagined real-life gorillas fighting Komodo dragons. He knew this fantastic story could only be told through “trick work.” But there was one thing he was adamant about: there would be no actor in a gorilla suit. Enter Willis (“Obie”) O’Brien, the special effects wizard who had worked on the silent classic The Lost World (1925). O’Brien had perfected the stop-motion technique. In this process, a model is animated and photographed one frame at a time so that when the film is projected the model appears to be moving. O’Brien had been working on a costly project at RKO called Creation (1931), which Selznick eventually scrapped. But the dinosaur footage that O’Brien had already shot gave Cooper the idea for how to tell his story. The door to O’Brien’s workshop led to new possibilities on the screen, and with it, Cooper’s gorilla grew even larger. But what he saw in his mind would have to be translated to the page.

British mystery writer Edgar Wallace worked on a rough draft of the screenplay (as well as the novelization), and although he was given a screen credit for King Kong, little of his work made it to the screen. James Creelman and Ruth Rose would write the final screenplay. Rose was Ernest Schoedsack’s wife and had accompanied both Cooper and her husband on many of their adventures. She based the characters in the screenplay on them. “Put us in it,” Cooper had told her. “Give it the spirit of a real Cooper-Schoedsack expedition.” As a result, First Mate Jack Driscoll, who rescues Ann Darrow on Skull Island, bore more than a passing similarity to Ernest Schoedsack with his tough exterior. The character of Carl Denham– the no-nonsense showman who captures Kong—was a reflection of the vibrant Merian Cooper himself. Besides the autobiographical material, some of Ruth’s contributions during the rewrites included 90% of the dialogue, streamlining the mythic story, building up the suspenseful opening, and playing up the fairy tale quality of its beauty and beast theme.

(clockwise) Merian Cooper with Fay Wray, Ernest B. Schoedsack, and Willis O’Brien.

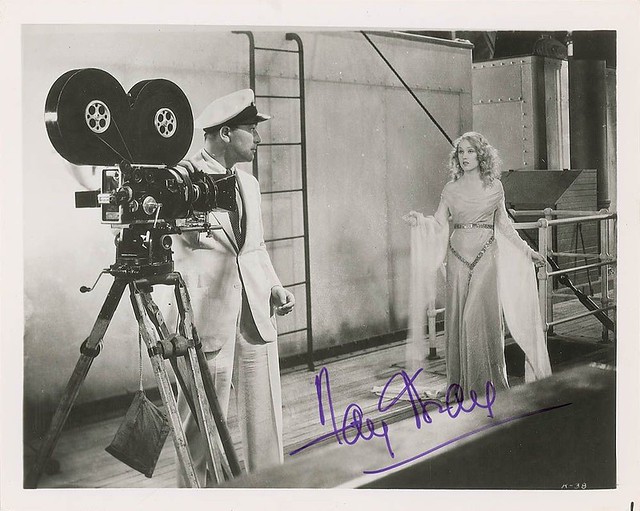

As they had done before, Cooper and Schoedsack worked together on the film but this time with both men directing different parts of the movie. Cooper supervised the effects work while Schoedsack shot the dialogue scenes. During Kong’s eight-month production schedule, Schoedsack made another film concurrently on the RKO soundstages, The Most Dangerous Game (1932). Cooper knew it would be cost-effective to use the jungle sets for both films. He also used many of the same actors in both productions. Fay Wray, who starred opposite Joel McCrea in The Most Dangerous Game, had worked with the two directors previously on The Four Feathers. Prior to starting Kong, Fay was informed by Cooper that she would be working with the “tallest, darkest leading man in Hollywood.” She imagined Clark Gable, but Cooper, of course, had other ideas. As the lovely heroine of King Kong, Ann Darrow, Fay would forever be associated with a giant gorilla. Though Fay preferred to be remembered for her roles in such films as The Wedding March (1928), in her later years she had come to terms with her celebrity as a “scream queen” and had accepted her fate as the girl in the hairy paw.

Fay’s scenes in the film, particularly those depicting her in various states of near undress, remain quite provocative. Some of these moments with Kong were in fact removed after the film’s initial release. King Kong, among its many other genre classifications, is also a notable “pre-Code” film and was released at a time when Hollywood’s Production Code was not being rigidly enforced. When the film was later reissued, starting in 1938, several scenes depicting Kong’s violence– as well as his curiosity over Ann– were removed to appease censors. One such scene had Fay being held in Kong’s paw while he removed and sniffed pieces of her dress. This scene, as well as others, were later restored and reinserted into prints of the film in the mid-1970s.

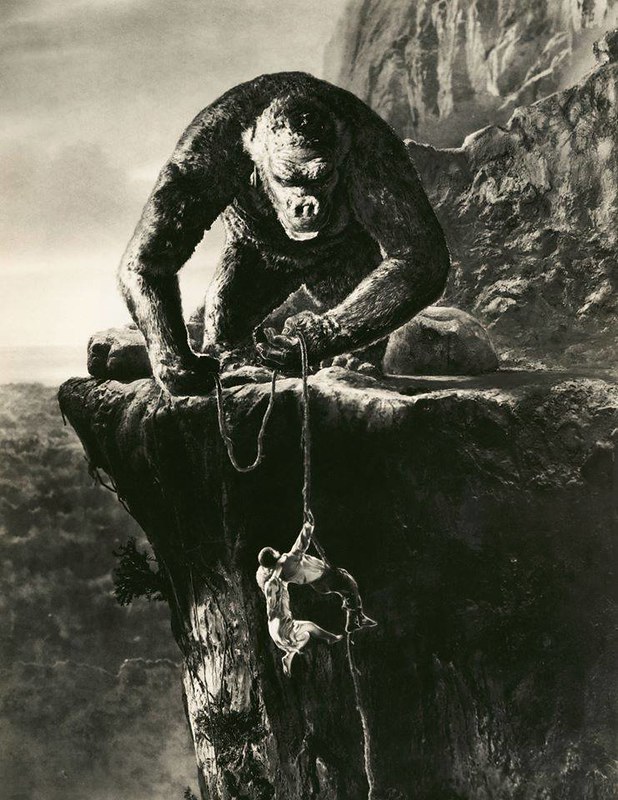

Robert Armstrong portrayed producer Carl Denham and Bruce Cabot, in his first starring role, was given the part of Jack Driscoll. The rest of the cast included such fine character actors as Frank Reicher (Captain Englehorn), Sam Hardy (Weston), Victor Wong (Charlie the cook), and Noble Johnson as the Native Chief. But the key actor—the one who needed to be most convincing to put the story over—was King Kong himself. Though he was supposed to be 18-to-24 feet in height onscreen—his dimensions often exceeded that for dramatic effect—he was actually played by an 18-inch tall armature. This metal skeleton, covered in foam rubber and rabbit fur, was designed by sculptor Marcel Delgado. In the Kong remakes and reboots that followed, particularly in recent decades, Kong is simply a large, silver-back gorilla– literally a big ape. Although the original Kong was certainly a gorilla, he was not quite a real gorilla. There was something abstract about this creature, a nebulous image we remember from a nightmare, and so its features are not quite exact.

In addition to its revolutionary use of technical effects like stop-motion animation, matte paintings, and rear projection, King Kong set a new standard in music. Max Steiner’s thrilling musical score, performed by a 46-piece orchestra, is one of the greatest in movie history. Rather than simply being background music, this was the first time a thematic score had been composed for a sound film. Kong had his own three-note musical motif, which is first heard over the main titles. Image and sound beautifully complement each other throughout. The film is a perfect example of how an evocative score can enhance the visuals.

When King Kong opened in March 1933, it was a monster hit. The ability to pull in over $2 million at the box office on its initial release was an extraordinary accomplishment considering it came at the height of the Great Depression. No theatregoer had ever seen anything like King Kong before. Willis O’Brien’s effects were ahead of their time. Long before computer-generated imagery gave us new worlds in pixels, O’Brien and Kong’s production team meticulously fashioned a dream-like world that looked like a Gustave Dore engraving. The prehistoric realm of Skull Island is detailed and nuanced with a dawn-of-creation quality effectively conveyed in black and white. One of the most exciting scenes in this setting is Kong’s battle with a T-rex while Ann watches helplessly from a treetop in the heart of the jungle. This scene was actually the “test footage” that Cooper had used to sell the project to the RKO board.

But it would be the image of Kong atop the Empire State Building that would stay in our collective consciousness. It’s the climactic moment of the film when Kong, having escaped from a Broadway theatre, heads to the tallest point in New York—with Ann Darrow in his paw. At the summit, he will place her down on a ledge to do battle with the biplanes. (Ironically, Cooper & Schoedsack play the two pilots who eventually shoot him down.) The beast’s demise is a tragic moment and we feel sympathy for this creature who has terrorized the natives of two different worlds. What is striking is the emotion that is registered on what is essentially a puppet. It is a testament to the great artistry of Willis O’Brien that this animated figure can affect us so deeply. Even now, in a more jaded age that seems to know everything—or thinks it knows everything—there is something magical at work on the screen that is more than the sum of its technical parts.

Willis O’Brien would do the special effects for King Kong‘s sequel, Son of Kong, which was released later in 1933. Son gives the impression of something hurriedly put together to capitalize on the success of Kong. Despite this handicap, the film, which is more about the fate of Carl Denham than the Eighth Wonder’s offspring, has a nostalgic charm and a resonance that many of the Kong remakes and rip-offs do not possess. O’Brien also worked on Cooper and Schoedsack’s 1949 gorilla picture, Mighty Joe Young. This final collaboration was essentially a movie for children but benefits greatly from the added contributions of Ray Harryhausen, who assisted O’Brien on the stop-motion animation. Although the Cooper-Schoedsack films that followed in Kong‘s wake had their moments, nothing ever recaptured the magic of the 1933 original.

As the years have gone by, the film’s influence has been sustained through revivals and re-broadcasts, and Kong continues to beat his chest in pop culture. Even on the smaller screen we see references to him in ads like car commercials. As we inch closer to Kong’s mighty centennial in 2033, we can be certain that he will be remembered by all his old friends—the fans who have kept him alive in our imagination.

~MCH

Note: Portions of this article originally appeared in the Winter 2018 issue of The Nostalgia Digest: “It’s Good To Be King: Remembering the 1933 Movie That Drove Audiences Ape” by Matthew C. Hoffman.

Newspaper ad from April 21, 1933: King Kong premieres in Chicago!