Prior to the 2020 pandemic, it seemed like every two weeks a new superhero movie was being released. This was never the case in the 1970s and ’80s. When a movie like Superman (1978) hit the screen, it truly was an event. Since those days, the genre has skyrocketed at the box office with the popular Marvel and DC Universe franchises. Avid followers of comic books are everywhere, from Comic Con shows to the Internet. Some fans go so far as to offer up their own “fan-made” trailers, edits and re-imaginings of science fiction and fantasy films. These alternative looks at movies are typically nothing of consequence, but it does become something special when, instead of a fanboy, the filmmaker himself is involved in some capacity to present us with an alternative version of a film. In the following case, the project was inspired by the passion of these same comic book fans.

Superman II (1980) is a film I have vivid memories of seeing as a child. I was 6 years old when my father took me to the Randhurst Theatre in Mount Prospect, Illinois, to see it when it opened nationwide in ’81. Superman, like Star Wars and Indiana Jones, is a series that remains part of my movie DNA. The original Superman, in my opinion, is the greatest superhero movie of all time. Directed by Richard Donner, the film is unquestionably his greatest legacy– the one he will be known for a hundred years from now. As a kid, I wasn’t aware of the now legendary backstory behind its sequel, Superman II. I wasn’t paying attention to who directed it.

All I knew back in 1981 was that Christopher Reeve was the greatest superhero of them all. (And, I confess, Sarah Douglas as Ursa, in that sheer black costume with the split sleeves, was my first screen crush.) This production was ten years before things started to be done with computers and CG imagery, yet so much of the film– with its practical effects– still stands out in my memory. I never forgot the cool effect of Clark Kent running through the city alley and blurring into Superman, or the graceful way Ursa flew over the retreating astronaut, or the image of General Zod being flung into the giant Coca-Cola sign. All of it amazed me and all of it has remained with me. That’s a testament to the filmmakers and their imagination.

As the years passed, I learned more about the history of these films and how Richard Donner was the driving force behind them. He had been shooting the original and the sequel simultaneously before finally concentrating on the first picture in order to make its release date. As fans are well aware, Donner never finished the second film– despite having shot roughly 75% of it. (30% of it was retained in the theatrical version.) Due to a souring relationship with the film’s producers, Alexander and Ilya Salkind and Pierre Spengler, Donner was let go. He was replaced by director Richard Lester, who had worked with the Salkinds previously. Lester had said of Donner’s work, “I think that Donner was emphasizing a kind of grandiose myth. There was a kind of David Lean-ish attempt in several sequences, and enormous scale. There was a type of epic quality which isn’t in my nature, so my work really didn’t embrace that…That’s not me. That’s his vision of it. I’m more quirky and I play around with slightly more unexpected silliness.”

Lester completed the picture by re-shooting several sequences and adding new material in order to be credited as the director. The resulting film proved to be a solid entertainment with many wonderful sequences. Though it was successful, it didn’t quite measure up artistically to Donner’s first film. Some effects shots seemed rushed; there’s the infamous Gene Hackman double; and composer Ken Thorne’s score, though based on John Williams’ original themes, didn’t help matters. (The Superman theme itself is the best example of the difference, lacking the richness of Williams’ orchestration.) There were other cost-cutting measures taken throughout the film’s production. The most egregious, of course, was cutting Marlon Brando’s footage because the producers didn’t want to pay him. The Salkinds were cheap, and as a result, they sabotaged the sequel’s full potential.

Storywise, there were lapses in logic. Even though one is dealing with fantasy elements, there still has to be an internal logic. You establish that Superman has such-and-such powers, but then viewers are introduced to abilities that make you scratch your head. (The disappearing “game” he used to play in school is one such example.) Superman II also suffered from the debilitating slapstick seen in the Battle of Metropolis– the ice cream sight gag or the guy talking in the phone booth and being blown over. This was a warning sign and a precursor of the broad slapstick that would follow and which would eventually sink half of Richard Lester’s Superman III, one of the most schizophrenic movies in motion picture history. The second sequel is a film that is very good with Christopher Reeve… and very bad with everything else.

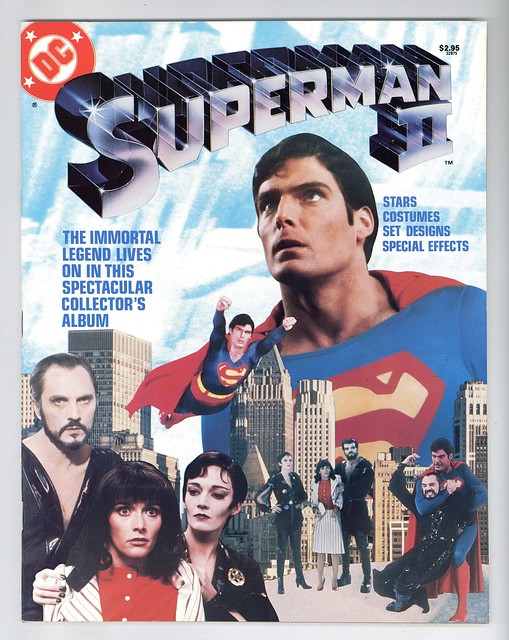

I still own my Superman II DC Treasury magazine…

Restructuring Superman

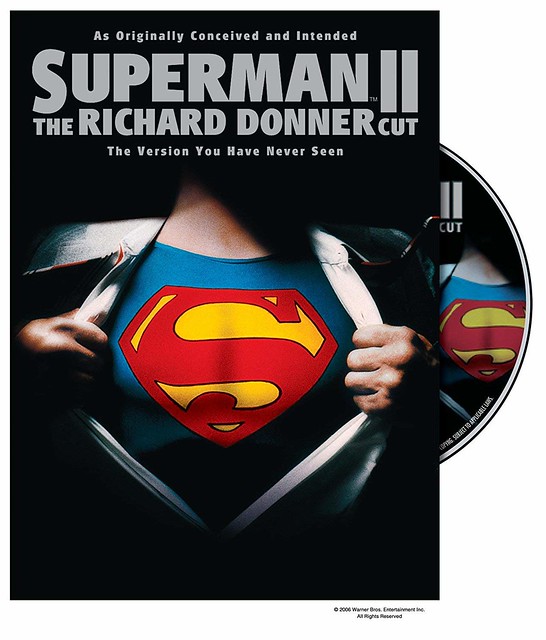

Over the years, as the global appreciation for the original film grew, and as fans became more aware of Richard Donner’s involvement in the sequel, there was a gradual clamor, fueled by the Internet, to see his version of the film– his alternate take on it. This project was realized in 2006 when Warner Bros. released Superman II: The Donner Cut. Painstakingly assembled by editor/producer Michael Thau, this was the version as it was intended to be seen. But it should be stressed that what exists is not the final version of what Donner’s film would have been. The Donner Cut represents the film as it was conceived, not necessarily as it would have been executed. According to Richard Donner, it was made somewhat to the degree that he would have liked to have seen it done.

It’s essentially a reconstruction by someone other than Donner that approximates his vision of the story. (The only Richard Lester footage in it are those shots that preserve the continuity of the story.) Many of the effects shots were never completed, and in one instance, footage from screen tests was used to complete a sequence. There would have been a final edit, so we have to keep all this in mind. It’s a film you can’t really judge since it’s technically not complete– nor will it ever be– but it serves as a fascinating coda to the Christopher Reeve/Superman saga. It makes you think about what could have been– and appreciate what was.

Lester’s Superman II opens with that stunning shot of the planet Krypton. This is followed by the trial of Zod, Ursa and Non and their subsequent imprisonment in the Phantom Zone. The whole sequence is dramatic– with the image of the green crystal filling the screen and transitioning into a nicely edited recap of the first film. Next, we have our first scene at the Daily Planet, which has Perry White telling Clark Kent about the terrorists in Paris. This was a new sequence that Lester shot and it works, although Richard Donner had a different opinion of the Paris opening when he saw it. (It was at this point Donner decided he didn’t want his name on the film.) To his credit, Lester could put together a serious, dramatic sequence when he wanted to. Think of the fire at the chemical factory in Superman III or the evil Superman’s battle with Clark Kent from that same film. Lester was an accomplished filmmaker who is probably best known for directing the Beatles in the musical-comedy A Hard Day’s Night (1964).

After Superman saves Lois Lane in Paris and disposes of the hydrogen bomb in space, the film returns to Metropolis once again with Clark Kent greeting Lois on the busy street and getting struck by a taxi cab. Lester has a multi-tiered introduction for the film– sequences that could’ve opened the film individually and which work together to complement the film’s multiple endings. (These will follow one after the other: climax in Fortress of Solitude and Clark’s kiss of forgetfulness with Lois/the diner scene/return to the White House.) These “loose ends” became a sort of trademark for the series.

By contrast, in the Donner version, which includes the Marlon Brando footage from the first film, there is a somewhat haphazard recap of events leading up to Superman throwing the missile into outer space. Here, the rocket hurtles into the cosmos and randomly explodes in the vicinity of the Phantom Zone, which then releases the three Kryptonian prisoners. “Free!” cries General Zod, before the opening credits zoom in. Lester’s version makes this catalyst a little more believable with the hydrogen bomb exploding (because it is set to do so) and sending shock waves through space, which crack the Phantom Zone. In Lester’s version, no dialogue is needed when Zod, Ursa and Non are finally released from their crystal prison.

The opening to Donner’s film also includes a sequence that had been shot much earlier in production. Margot Kidder looks noticeably different. She’s adorable when she suspects Clark of being Superman and proceeds to draw in an image of Clark over a picture of Superman in the newspaper. Lois then tests her theory by jumping out of a window without any hesitation. (She will wind up testing him again at the Honeymoon Haven Hotel with a gun: “I risked my life instead of yours,” she tells him in the later scene.) Perhaps falling from a building again– though with a different outcome– seems repetitive after the first film’s dramatic rescue. However, both Donner and creative consultant Tom Mankiewicz felt this was a wonderful way to open their film. Admittedly, it’s fun, sophisticated, and true to the spirit of Superman. Reeve and Kidder are so good in the scene it’s hard to argue against its inclusion at the outset.

Though Lester’s flaw was his slapstick, at least in relation to a Superman movie, his version, ironically, edits out much of the unnecessary banter between characters that had been established by Donner. Gene Hackman (as Lex Luthor) and Ned Beatty (as Otis) have great chemistry, but some of their lines could have been (and were) trimmed during the prison escape. Lines were likewise cut from some of the dialogue between Lex and Miss Teschmacher (Valerie Perrine) in the hot-air balloon during his escape from the prison yard. More of this excised comedy turns up in the “Deleted Scenes” on the Donner Cut DVD.

A good example of Lester’s trimming comes in the prison laundry and the removal of the joke about the bed-wetting prisoner. This stuff was shot by Donner, but it doesn’t necessarily mean he would have incorporated it into the final film, as Michael Thau has done. (For instance, there’s a three-hour television version of the original Superman that Donner has called terrible. He shot everything in it, but he knew he wasn’t going to use some of the material. Likewise, I’m sure there are things we are seeing in Superman II that he would have mercifully taken out.

Lester’s film is much more balanced than the Donner cut. In this new version, for instance, there is a brief scene of Clark and Lois being led to their room at the “Honeymoon Haven Hotel” –Lester footage that was expanded in the version we know– followed by a very lengthy sequence of Lex Luthor and Miss Teschmacher finding the Fortress of Solitude in the North Pole. Though it’s great seeing Marlon Brando manifest in Donner’s film, this sequence is substantially altered by Lester, who instead uses Susannah York (as Superman’s mother, Lara). Lester also excises Miss Teschmacher’s “flushing toilet” gag in his version. (So we lose Lester’s flying ice cream, but we gain a flushing toilet joke in Donner’s film!)

Richard Lester’s movie may be more dramatically even, but something is off with the score. You can tell this isn’t John Williams’ London Symphony Orchestra. Although composer Ken Thorne’s theme music sounds hollow compared to the fullness of Williams’ score, Thorne’s variations of the themes and motifs throughout are generally quite good. A case in point is the villains’ arrival on the Moon. Obviously, John Williams would have composed a magnificent score for Superman II had he been involved, but for this version, producer Michael Thau could only work with pre-existing music and unused cues from the first film. The score is another aspect of the Donner cut that can’t be evaluated, but Thorne does make dramatic use of music throughout the theatrical cut, especially where he places the Superman theme.

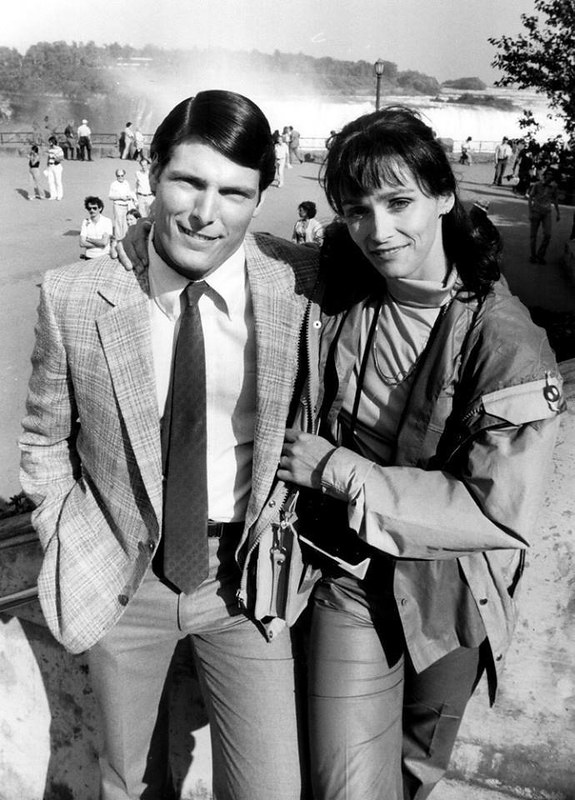

A moment in time… Chris and Margot on location at Niagara Falls.

Richard Lester’s film, which is 127 minutes, has sequences that are severely cut in Donner’s version. A good example of this is Clifton James’ sheriff and his deputy confronting the three “hippies” in the middle of the road. Lester also extends the East Houston scenes with that memorable moment in which Ursa “holds hands” with one of the rednecks in the cafe. And there’s Ursa’s airborne kiss that sends the helicopter crashing into a barn. It’s terrific stuff, and they’re good examples of how the underscoring heightens the action.

One of the shots in the Donner cut that is a substantial improvement is the one depicting the villains destroying the Washington Monument, which topples over. In the Lester version, they deface Mount Rushmore and carve their own images into the mountainside with some kind of power we are not privy to. Then again, if they are destroying monuments in Washington– apparently on their way to the White House– most likely the President would not be sitting in the Oval Office watching it on television! Donner’s cut also has more destruction in the White House, including that great shot of General Zod pulling a soldier through a window by the barrel of his machine gun and then using it on the troops. Donner had always wanted to stress the danger of these villains and to depict them as a real threat. Lester’s version retains most of this footage and presents us with just enough action before Zod’s meeting with the President, which was all shot by Donner.

The storyline of Superman II, which is the same in both versions, has Superman falling in love with Lois Lane. This is developed more strongly in the Lester version. As a kid, I always had issues with that “pink bear” that Clark Kent trips over, which essentially changes the course of the film. Kids like me didn’t want to see Superman fall in love. His “reveal” in Lester’s film is nevertheless well-acted, and its execution stands in contrast to the “Gotcha” moment in Donner’s version with Lois shooting a gun with blanks in the hotel room. (Superman wouldn’t have seen the gun or noticed it was a blank? Wouldn’t someone in the hotel have heard the gunshot?)

But again, this rediscovered footage was taken from Reeve’s and Kidder’s screen tests, so had it actually been shot, it most likely would have played much differently. Its inclusion here does reconnect us to the beginning in which Lois jumps out of the window at the Daily Planet. Having grown up with the theatrical version, though, I feel the scene in which Lois jumps into the river is stronger and more practical.

One issue that I have with the romance element that unfolds afterward is that in the Donner cut, Superman sleeps with Lois first and then gives up his powers to remain with her. In Lester’s version, this is reversed. It’s an important detail that Lester changed from the original script. Generally speaking, how Lester and his editors arranged the scenes just makes more sense and gives the picture a more natural flow.

The molecule chamber sequence, where Superman is “destructured” and loses his powers, is one of the biggest differences between the two films. In the theatrical version, Superman speaks to his mother about his love for Lois. In the Donner version, this is performed with Marlon Brando as Jor-El, who tries to convince his son to reconsider his actions. Brando’s inclusion in the film as a whole completes the story arc, so incorporating the mother in the Lester version makes little sense except to show a mother’s love. Another difference in these scenes is that the tone of Christopher Reeve’s performance shifts slightly from being a little more sympathetic with his mother to being more aggressive, even selfish, with his father. “Haven’t I served them enough?” he asks of his obligation to the world. But he is making a mistake, one that is perhaps more keenly felt in the Donner version because of his intensity. It’s a mistake he himself will recognize by the time he tastes his own blood.

There’s a wonderful shot of Brando giving Lois Lane the evil eye as she backs away from her ledge in the Fortress of Solitude. In Donner’s version, however, Lois is simply a presence and nothing more. Her wearing of Superman’s shirt in this scene just seems inappropriate. (Supposedly, Donner and Mankiewicz had an argument over this.) In Lester’s cut, she’s in a robe at least, and we see her reacting more to what is transpiring below her. Additionally, Lester’s re-imagining of Superman losing his powers is more cinematic with Superman simply fading away inside the chamber while the powerless version of Clark emerges and walks away to a new life.

Marlon Brando has another key scene later in which, as a hologram, he transfers the last bit of energy that connects him to his son. Brando’s lines are deeply moving, but his interaction with Kal-El raises more questions. By contrast, this is all left to the viewer’s imagination in Lester’s film where Superman sees the green crystal light up and takes it in his hands. He finds his powers again rather than having them given to him explicitly by his father. There was no need to see him being charged up by his father’s energy. At the same time, how do you cut out Marlon Brando? His presence elevates anything he’s in.

Superman’s return to Metropolis in Lester’s version is one of the highlights of the film with the famous line, “General, would you care to step outside?” In the Donner cut, on the other hand, it’s less dramatic with Superman appearing almost immediately, standing on the flagpole with the line, “General, haven’t you ever heard of freedom of the press?”

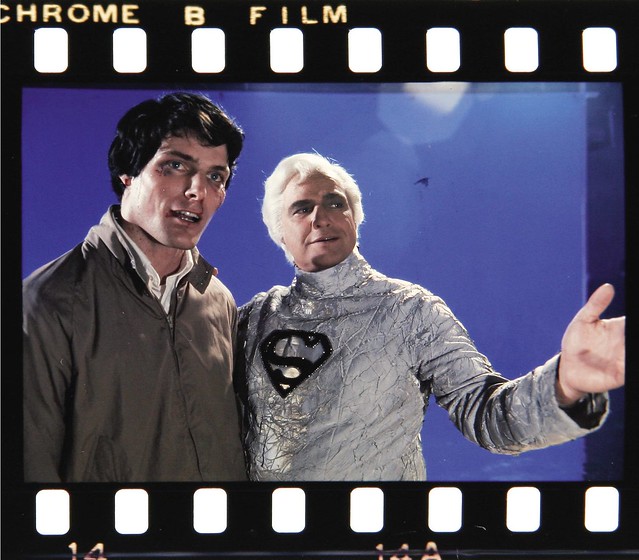

Christopher Reeve and Marlon Brando together (finally) on screen. Photo courtesy of Superman ’78.

The Battle of Metropolis features some significant differences. Again, the effects work in Donner’s version was never completed, so digital technology here gives us an approximation of how the sequence might have played. The crudeness of some of these shots is something that can’t be criticized. It’s interesting comparing the two battles, the different set pieces (the Statue of Liberty) and the varying lines of dialogue: “What, you hit a woman?” Generally speaking, Lester’s battle is pretty spectacular– marred only by the wind-blown comedy towards the end. It’s not just that the slapstick doesn’t belong, but it strikes at the very core of the verisimilitude that Donner was always striving for. If the people in the street don’t care what’s happening– the guy on the phone and such– why should the audience?

There are also additional edits to the dialogue; some of Lex’s lines were cut, and there are alternate line readings. For example, after the battle when the villains return to the Daily Planet, Terence Stamp’s Zod asks Luthor, “Why do you say this to me when you know I will kill you for it?” The line is given a more rhythmic delivery by Stamp in the Lester cut. When I first noticed this, I thought it could be an alternate take that Donner had shot and which Michael Thau had decided to use. (Thau had in fact made use of alternate shots and different angles in the opening scene when Zod is shouting at Jor-El after his guilty verdict.) However, I believe this is actually a scene re-shot by Lester and then edited in with the existing footage of Gene Hackman.

We come to one of the biggest differences between the two versions, and that’s the ending. For years, a friend of mine has joked about the bad Gene Hackman double– the guy who gets dumped in the Fortress of Solitude and demands, “Hey, ever heard of parachutes?” In the Donner cut, the villains arrive at the Fortress with Lois and Lex, and then Zod calls out to Superman, “Coward! Son of a coward!” Superman emerges from within the molecule chamber, there’s some finger-pointing, and then we pretty much go into the ending that we know. Having seen Donner’s version, I can actually appreciate the reasons why there is a Hackman double in the theatrical version. Lester extended this sequence at the Fortress, and since Hackman was not available for re-shoots, Lester was forced to do it this way. Gene Hackman, in fact, never shot a frame of film for Richard Lester. It was one of those, “Oh, now I see why he did that!” moments for me as a viewer.

In Lester’s film, General Zod has improved dialogue, and there’s that line about the Fortress having “no style at all.” Lester then cuts to the dramatic shot where we see the villains framed within Superman’s boots. “I expect better manners, General.” That is a legitimately great moment and visual. There are some added bits of business, including a moment when Zod absolutely loses it in frustration. There’s the aforementioned disappearing trick, and although this stuff may fall outside the abilities that have been established for the character, I give Lester credit for adding on to the sequence. The Donner cut has the climax almost immediately, but Lester made it more interesting, even if you’re not a particular fan of energy beams shooting out of the fingers.

The climax gives way to the resolution which, in Donner’s film, is the biggest flaw. There is a lovely scene at the North Pole between Superman and Lois Lane. “Don’t ever forget,” she tells him. He takes her back to her apartment in Metropolis where she reassures him that his secret is safe with her. It is shortly after this, however, that he turns the world back– not just moments, as in the first film, but apparently for days! We see a typewriter going in reverse with text disappearing, and there’s Perry White with his suspended toothpaste. But Superman takes us all the way back to where the villains are once again imprisoned in the Phantom Zone! (The “turning back time” idea was conceived for the sequel but consequently used to better effect in the original. Superman: The Movie was going to end with Superman throwing the rocket into space and thus freeing the super-villains. The original would have ended on a cliffhanger much like the serials of the 1930s and 1940s that had inspired it.)

Not only is this ending a major cheat, effectively telling us everything we just saw didn’t happen, it actually puts the world back in danger. The criminals are no longer imprisoned/lost in the bowels of the Fortress of Solitude but are now back in space (with the potential of being released again)! So the world has to go through this again all because Lois mustn’t know his secret? The sequence, which leads back to the Daily Planet, does create the quality of a dream remembered with the “North Pole” briefly popping into Lois’ mind as she struggles for a headline. But I would say that Lester wisely used the magical kiss as a better device to erase her memory. Silly? Perhaps, but it’s more acceptable than the other version.

Aside from the kiss itself, this whole scene in Lois’ office is the emotional climax of Lester’s film. It’s Margot Kidder’s best piece of acting, too. The resolution of this personal drama was eloquently conveyed at the North Pole in the Donner cut, but here, it’s just as powerful in the Daily Planet. Tom Mankiewicz had always felt that Clark Kent should never kiss Lois– only Superman should kiss Lois. But in this moment, Lester does have Clark remove his glasses.

For more about the making of the Christopher Reeve Superman films, visit www.capedwonder.com, the definitive website.

Finally, Richard Lester takes us back to the diner (like Donner) where Clark teaches the trucker a lesson in manners. Donner’s version ends with this scene (which now makes less sense because the bully is effectively a stranger since they never actually met) before taking us back into space with the memorable Superman flyover. But Lester gives us one more sequence afterward, and it contains one of the most iconic images in the entire series: Superman returning the American flag to the White House. It’s the perfect capper to a wonderful movie.

The “Donner Cut” is unprecedented in movie history. I can’t think of another instance where a film exists in two different versions (with the same cast) made by two filmmakers. What Michael Thau has put together from the camera negatives he found in England– six tons of footage– is not superior to Richard Lester’s version as a whole, although many fans prefer this cut. Would Donner’s version– not the Donner Cut that we have here– have been better than Lester’s (hypothetically) had he stayed with the project? Definitely. Richard Lester was filling in the pieces to a puzzle that Donner had created. Lester had another sequel to prove himself unique and we know how well that turned out. Donner was clearly the better choice to direct a Superman movie. As he himself has pointed out, his successor simply reverted to the “face value of the comic book rather than the heart.”

Yet, there are many fans out there who prefer Lester’s version– not just to the Donner cut, but to the original film. I once had a film teacher at Columbia College tell me he preferred the sequel, and pressed why, he said because he couldn’t take a movie about a man in tights seriously. It’s a broad statement to make, but maybe people who don’t take the subject seriously prefer Lester’s handling of the film while those that do, who feel Superman deserves that mythic quality, prefer Donner’s interpretation.

It’s one of cinema’s great tragedies that Richard Donner never completed the saga since he was so emotionally invested in it. He had formed a great production unit with talented craftsmen, and they could have gone on, like the James Bond series. There was always a comfortable familiarity about Reeve’s Clark Kent arriving at the Daily Planet and the audience seeing characters we had grown to love. The Superman films were more than just escapism. These movies recognized the positive things in life, and through Reeve’s interpretation of Superman, we saw the inherent goodness of humanity and what we ourselves could become (minus the x-ray vision, of course). There was a decency and moral strength about Christopher Reeve in this role, and that’s why we always cheered for him. He made us want to be the good guy.

The Donner Cut is dedicated to Chris and for good reason. When the original was being cast, every leading man in Hollywood was considered for the role, but no one, no matter how good an actor he was, would have come close to what Chris did on screen. As the dedication card says, without him, we never would have believed a man could fly.

~MCH

Every great hero needs a great villain. Superman II had three of them– or four if you count Non twice.