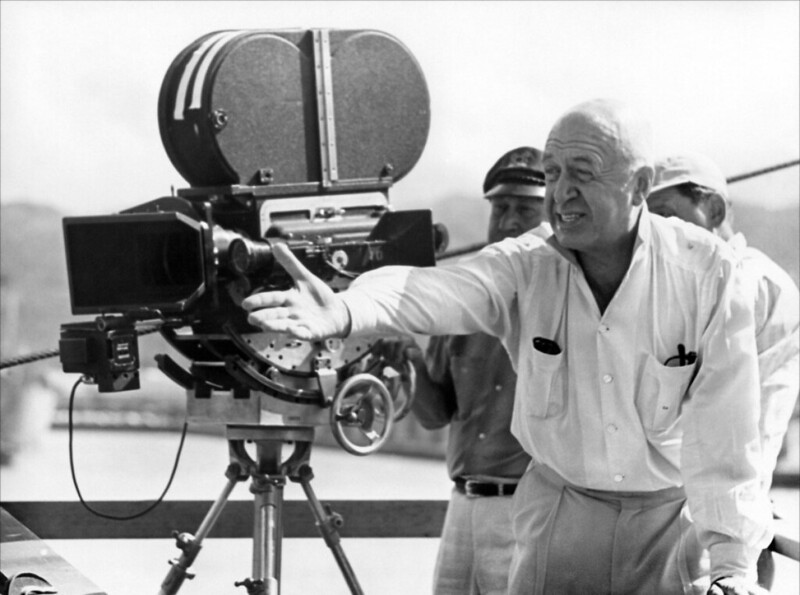

A post on one of my least favorite “major” directors– Mr. Freeze himself, Otto Preminger.

Otto Preminger was a hack– at best, a functioning director on the level of a Lew Landers. His fame, or rather his notoriety, rests solely on the controversial nature of the story material he chose to exploit in otherwise dreary fare such as The Moon Is Blue, The Man With the Golden Arm, or Anatomy of a Murder (actually, entertaining “adult” fare–for 1959– but nonetheless overlong and slow-moving).

Anatomy has its moments but it is basically just another of Otto’s then daring “controversy” pieces remembered chiefly for the then-unheard of use of such pre-Code words as “panty” and “virginity,” in the course of its extremely long running time of 160 minutes. If the viewer can weather the talky and static dramatic sequences and manage to stay awake through the elongated courtroom scenes, one can witness the emerging talents of George C. Scott or happily coast on the eye-pleasing diversion of Lee Remick. The pacing is as leaden as a crawl through a graveyard.

I only complain about the length of a film’s running time when said film is BORING– you know, like almost everything Preminger ever made, or at least, received directorial credit on. I could sit through the nearly 3-hour The Best Years of Our Lives twice a day for the rest of my life, but that happens to be a brilliant piece of cinema, persuasively directed, a concept as foreign to Otto as a comb.

I’ve enjoyed many of his films for the stars or the programmer quality of the productions, but certainly not for any outstanding directorial flourishes. He was to my mind a simple 1-2-3, by the manual, studio contract ring-master. In regards to Laura, Preminger should get credit for “fleshing” out the movie’s characters in the revised script before taking over the floor-plan that Rouben Mamoulian had mapped out. Otto directed Laura only in the sense that Christian Nyby “directed” Howard Hawks’ The Thing! Fallen Angel is probably my favorite of his film noirs, but realistically, it’s hardly a good story and badly executed. The trampy Linda Darnell in the road-side cafe is the whole show while the top-billed Alice Faye is wasted and frankly out of her element. Considering it’s supposed to be a deep-dish murder mystery, the suspects are reduced to one logical, obvious choice– and Charles Bickford does everything but wear a neon sign on his hat declaring I DONE IT! Except for that really neat ending involving a car, the reverse gear and a very surprised Robert Mitchum, I can’t remember anything else about Angel Face. Where the Sidewalk Ends is an attempt to retool Laura.

I once knew a “cinemah” enthusiast who was enamored of Preminger’s use of ‘Scope in In Harm’s Way. For starters, I’d like to have a nickel for every production lensed in Panavision that some expert somewhere labels as CinemaScope. Believe me, there is a world of difference in the two processes– depending on the focal length– in contrast, clarity and composition. That aside, what’s so inventive about maneuvering that letterbox composition through the cramped quarters of one ship after another? There are just so many camera variants to play with, and I would tend to give more credit to a crafty editor than the cinematographer. That said, In Harm’s Way is nothing more than a routine war film, padded out in length and crammed with a lot of stars and notable character actors. The most memorable thing about In Harm’s Way is the truly awful ship models which look that much worse on a 100-foot screen. These are the worst miniatures– actually, “oversize” at some 12 feet each– this side of 633 Squadron.

This same Preminger fan I knew championed River of No Return. River is nothing more than a slick commercial vehicle designed by Fox and dropped in contract director Preminger’s lap, to promote the CinemaScope process and Marilyn Monroe– in that order. It’s a formula morality play dressed out with a stock revenge plot, heightened by some beautiful on-location background photography (courtesy of Joe LaShelle, not Otto), hampered by some crude “process” by Ray Kellogg, and almost sunk by a lot of awful, cliched dialogue; we’ll split the blame between story-writer Lou Lanz and screenwriter Frank Fenton– although I’m perfectly willing to allow “auteur” Otto the full credit. Bottom line: Preminger himself dismissed it as nothing more than a studio assignment. As such, Lew Landers could have phoned it in.

For an enlightening read on what a professional opportunist Preminger actually was, I recommend Scott Eyman’s biography on Ernst Lubitsch: Laughter in Paradise (1993). The book details Preminger’s involvement with the great Lubitsch and how he effectively butchered the projects Lubitsch was not able to complete himself.

Preminger’s success– I won’t use the word “talent”– was as a producer who also happened to direct. When controversy became fashionable, he simply moved to dull epics like Exodus and The Cardinal, distasteful thrillers like Bunny Lake is Missing, downbeat junkie-love like Tell Me That You Love Me, Julie Moon or the buffoonish Hurry Sundown, guaranteed to make everyone’s “turkey” list. All in all, the guy made a better Nazi in other people’s films than an auteur in his own.

~MCH