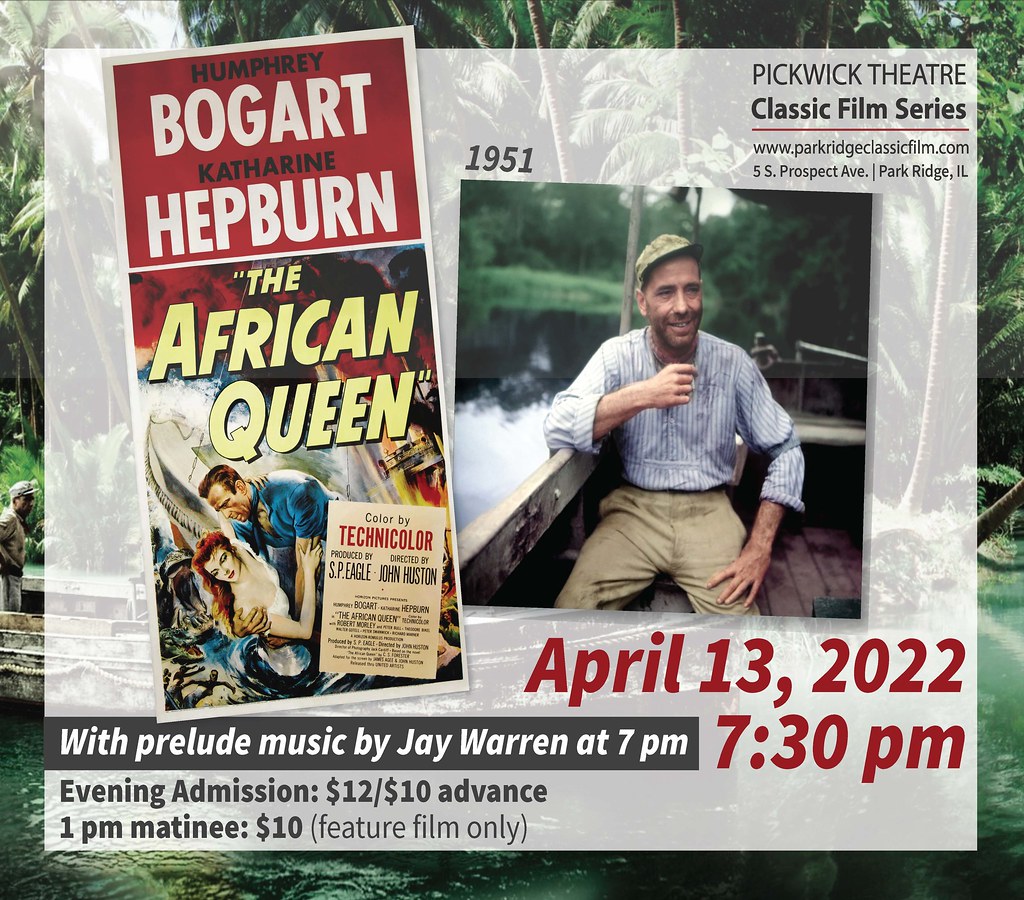

WHAT: The African Queen (1951, 4K DCP)

WHEN: April 13, 2022 1 PM & 7:30 PM

WHERE: Pickwick Theatre, Park Ridge, IL

WHAT ELSE: Organist Jay Warren performs pre-show music at 7:00 PM!

HOW MUCH: $12/$10 advance or $10 for the 1 PM matinee

Advance tickets: Click Here!

As Season 8 came together, we decided on a 25th anniversary screening of James Cameron’s Titanic (1997) for April. Coming out of a pandemic, we felt this was the surest way to draw a great crowd, particularly young people who remember the love story between Jack and Rose. The show was intended to coincide with the 110th anniversary of the Titanic‘s sinking, and it was the historical aspect that motivated me the most. I even started to assemble some props and memorabilia to display in the theatre lobby. However, there was just one problem: the studio wouldn’t let us show it. The film is currently out of circulation for one reason or the other. So then the question became, what do we show in its place?

The African Queen is a film we’ve wanted to present for a number of years. I pictured it either opening or closing a season; in both cases, that’s a high honor. It was just a question of when… In this current season–our first after the pandemic shutdown–we’ve shown films from the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, but nothing earlier. I felt this was the time to play the oldest film in our lineup. The African Queen would fill the hole left by Titanic. So instead of showing a movie with an actress named Kate who plays a character named Rose who winds up on a ship that sinks, we’re playing a movie with an actress named Kate who plays a character named Rose who winds up on a boat that sinks. And to be honest, The African Queen is a helluva better film than Titanic. It’s a romance for adults.

Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn star in this legendary adventure directed by John Huston. It’s the movie which won Bogart his long-overdue and well-deserved Oscar. Besides featuring two of the biggest stars of the day, The African Queen offers wonderful African locations– one of the few Hollywood films at that time to be shot in Africa– in Technicolor, no less. The film was photographed by Jack Cardiff, the preeminent Technicolor cameraman in the world. Thus, the opportunity of seeing these gorgeous locations in all their color in the Pickwick’s Mega-Theatre– in a 4K digital restoration– is an absolute must-see experience. If you’ve only seen this movie on television, you haven’t really seen it.

The African Queen is based on the 1935 novel by the accomplished storyteller C.S. Forester. Director John Huston always took stories from novels, and the book’s plot no doubt appealed to his adventurous nature. An opportunity to go to Africa was also an opportunity to shoot a bull elephant (which Huston never actually did). The money man behind this was producer Sam Spiegel, whose production company was Horizon Films. He would go on to produce such films as The Bridge on the River Kwai and Lawrence of Arabia. Spiegel was able to secure the rights to the book. He then pitched it to Humphrey Bogart, who told him he had never worked with Katharine Hepburn; both stars wanted to make it. An industrious man who knew how to round up finances, Spiegel next sought out producers John and James Woolf (of Britain’s Romulus Films). The brothers were willing to get Spiegel’s project into production.

This was a time when there was much political strife in Hollywood in the McCarthy Era. Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall had been on the committee for the First Amendment and had traveled to Washington to make their feelings known. The Bogarts weren’t even remotely Communists, but any expression of freedom of speech in those days often got one branded as left-leaning or un-American– labels that could affect one’s status at the box office. Huston, too, was part of this idealistic milieu. Ironically, all would leave Hollywood to make a film about patriots doing their part for the war effort.

The brilliance of The African Queen‘s script rests in the contributions made by James Agee, a talented film critic who was breaking into the movie business. He had caught the eye of Huston, who had read Agee’s article on the director for Life Magazine called “Undirectable Director.” Their meeting would lead to a brilliant collaboration. Agee supposedly based the Charlie/Rose relationship on that of his own mother and father. (Interestingly, the main character, Charlie Allnut, was written as a Cockney, but since Bogart was involved, they changed him to Canadian.) Writer Peter Viertel was also brought in to work on the story, mostly with the ending.

In the days of the First World War, Rose (Katharine Hepburn) is a strait-laced missionary dutifully spending her time with the African locals. When the German army destroys their village, Rose’s brother (Robert Morley) is injured and eventually dies. Along comes Charlie Allnut (Humphrey Bogart), owner of the African Queen boat. He stops by the decimated village and offers to take Rose away. Charlie is a gin-swilling river rat whose manners and vices are abhorrent to the prim and proper Rose, but she needs his help. Rose wishes to destroy a certain German gunboat. Charlie balks at the far-fetched idea, but in time, their perseverance and ingenuity lead to a confrontation with the Germans — and a surprising result.

The African Queen was shot primarily in two locations in Africa: along the Ruiki River in the Belgian Congo and in Uganda. Since the 35-foot African Queen was not big enough to hold the large Technicolor camera, mock-ups of the boat were built and carried atop a raft. Depending on what shot was needed, these segments were pulled along the river with a parade of other boats containing the crew and equipment (which did not always follow the bend of the river). Lauren Bacall was also with the company and proved to be an invaluable asset. She helped cook for the crew and serve as a nurse maid.

“While I was griping, Katie was in her glory. She couldn’t pass a fern or berry without wanting to know its pedigree, and insisted on getting the Latin name for everything she saw walking, swimming, flying or crawling. I wanted to cut our ten-week schedule, but the way she was wallowing in the stinking hole, we’d be there for years.” ~Humphrey Bogart

John Huston was a filmmaker who was drawn to adversity and sought the adventure that lay beyond the confines of the Hollywood studio. Part of the attraction for Huston was to see Africa and to go hunting. In her memoir, The Making of the African Queen, Katharine Hepburn writes of her desire to go with John Huston on the hunt. Although she loathed the act of killing anything, she wanted to know what it was all about. At one point, they were nearly crushed by an elephant stampede after following a herd into the underbrush. Huston’s adventures in Africa were the basis of writer Peter Viertel’s book, White Hunter, Black Heart. It was not exactly a flattering portrait of Huston, but he had suggestions for Viertel to make the main character, “John Wilson,” even less flattering! These exploits were later made into the 1990 film starring Clint Eastwood.

Huston could be unorthodox, but no one questioned his genius as a filmmaker. He and Bogart were cut from the same cloth and they made some of their best films together. Huston had written High Sierra, which had been a major breakthrough role for Bogart, and his first film as a director was The Maltese Falcon. More recently, the two had made The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, which had been shot in Mexico. Like many of his films, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre was reflective of his themes about defeat. These stories typically centered around losers of some sort. The African Queen, however, veers off from that track because things do work out in the end. This more upbeat vision was undoubtedly the result of Bogart and Hepburn’s chemistry on screen. Huston saw the magic and knew he had to deviate. How could these two characters lose? (In the novel, Charlie and Rosie do fail in their mission.)

Katharine Hepburn expressed her uncertainty about Huston, at least at the outset. Her main concern before leaving for Africa was the screenplay and not seeing a completed version of it. In her eyes, Huston was more concerned about bringing his guns than a script. But Huston was able to put her at ease and help her discover her character. Hepburn later raved about Huston’s direction, particularly some advice he had given her which she called the greatest piece of direction she had ever received. She hadn’t yet found the Rose character and was perhaps coming across as too sombre in her portrayal. In his laconic way, John Huston asked her if she had ever seen the newsreel footage of Eleanor Roosevelt visiting soldiers in the hospital. He made her think of the smile Eleanor always seemed to have while performing that difficult task. He projected that image onto Hepburn. As a result, her own beauty emerged when she added that simple, “society smile.”

On this film, Huston had the great fortune of working with cinematographer Jack Cardiff, who was, at that time, the greatest color photographer working in cinema. He is best known for the Technicolor films he made with Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, including Black Narcissus and The Red Shoes. Although he downplayed his work on The African Queen, the African locations are stunning to behold through his lens. For this particular production, Cardiff insisted on bringing two lamps and a generator with the camera. Even though the African sun was brilliant, often times it would be raining, and having the lights there proved essential. The Technicolor camera itself was a massive mechanism, so lugging it through the Congo was no easy task for the crew.

John Huston (left) with Bogart and Hepburn…

There were many hardships during the making of the film, which Hepburn details in her book. At one point, the African Queen sunk in the river. “The natives had been told to watch it and they did,” Lauren Bacall said. “They watched it sink.” Everyone had to help pull her upright using a rope looped over a tree branch. In addition, soldier ants invaded the jungle camp, and at one point, Hepburn found a black mamba snake in the women’s outhouse. But the worst was when Hepburn and others got sick because of a bug in the water. She became extremely dehydrated and couldn’t keep anything down. The scene of her playing the organ in the church was shot right at the time of her illness, and her face does appear rather sunken in these shots. Huston and Bogart, on the other hand, never got sick primarily because of all the Scotch whiskey they had lined their stomachs with.

The film was finished in England. The studio sets (at Isleworth Studios, Middlesex) were necessary. For one thing, the water in Africa is poisonous, so there were no shots of Bogart or Hepburn in the water while on location. All the water scenes were shot using a special tank, including the sequence in which Bogart repairs the boat’s propeller underwater. At this stage in the production, other effects were incorporated, such as using a miniature of the African Queen in the rapids. This was later inter-cut with shots of Bogart and Hepburn against a blue screen.

Upon its release, the reaction to The African Queen was all positive. Humphrey Bogart was nominated for Best Actor, but he didn’t believe he had a chance to win. The competition was tough. Also nominated that year were Marlon Brando (A Streetcar Names Desire), Fredric March (Death of a Salesman), Montgomery Clift (A Place in the Sun), and Arthur Kennedy (Bright Victory). Bogart won. Lauren Bacall had no doubt he would. Audiences loved his characterization of Charlie Allnut. In addition to Bogart, Katharine Hepburn was nominated for Best Actress and John Huston for Best Director. The screenplay by Huston and James Agee was also nominated. The British Academy Film Awards and the New York Film Critics Circle Awards both nominated The African Queen for Best Film.

Then, as now, moviegoers gravitate towards these two characters. The African Queen shows us two great performances from two screen icons. It’s an adult love story interpreted by two mature leads. Maybe seeing two older people in the mud might not have the same appeal for younger viewers, but the story is told with such intelligence, humor, and warmth that it’s hard to imagine anyone not being engaged by it. It’s a film with universal appeal that has stood the test of time– a film that continues to captivate and entertain. Over seventy years later, The African Queen is the film that is unsinkable.

~MCH