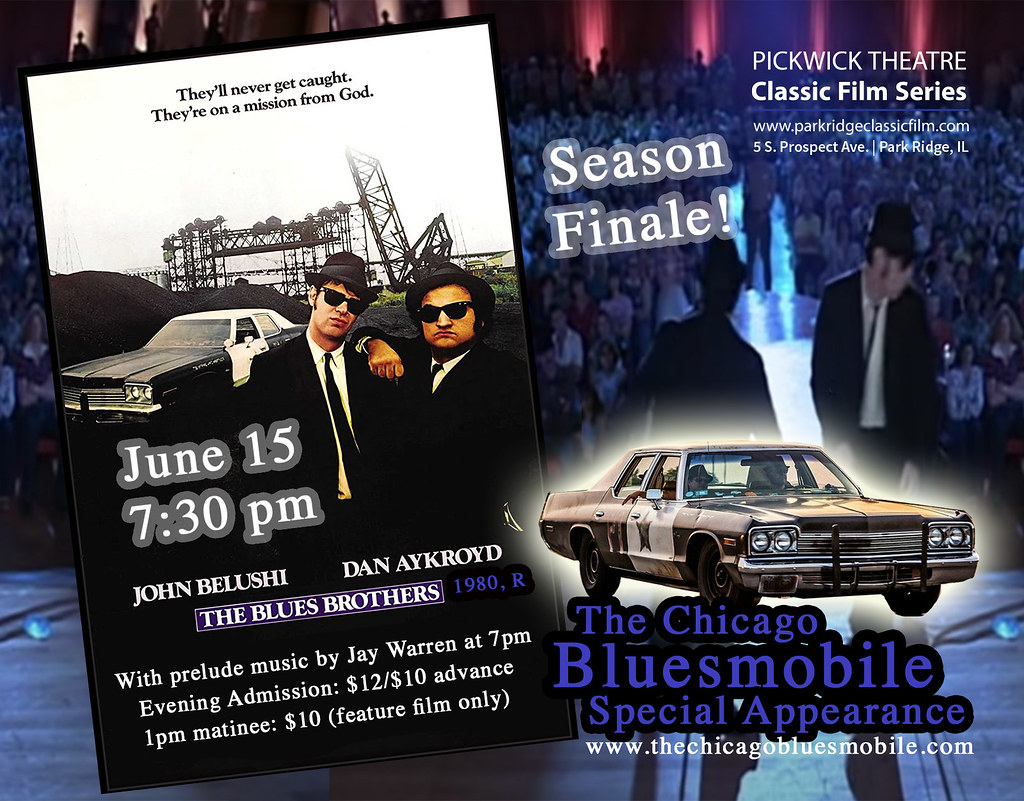

WHAT: The Blues Brothers (1980, DCP, theatrical version)

WHEN: June 15, 2022 1 PM & 7:30 PM

WHERE: Pickwick Theatre, Park Ridge, IL

WHAT ELSE: Organist Jay Warren performs pre-show music at 7 PM; cartoon at 7:30 PM; and the “Chicago Bluesmobile” parked in front of the theatre between 6-8 PM!

HOW MUCH: $12/$10 advance or $10 for the 1 PM matinee.

Advance Tickets: Click Here!

NOTE: This film is Rated R for strong language.

Elwood: It’s 106 miles to Chicago, we got a full tank of gas, half a pack of cigarettes, it’s dark… and we’re wearing sunglasses.

Jake: Hit it.

Is there a film more associated with Chicago than The Blues Brothers? Is there a film more beloved by Chicago than The Blues Brothers? Beyond its local connections– including scenes shot right here in Park Ridge– the film is remembered for being a great comedy and a great musical. Simply put, it’s a great film. We originally planned to show it in 2020 for its 40th anniversary, but due to the pandemic, our screening has gotten pushed into 2022. So with the Chicago Bluesmobile parked outside, and a theatre full of fans inside, this is certain to be one of the most fun nights we’ve had in a long time.

The characters known as “The Blues Brothers” are legends, and the film in which they star has become something more than just a “cult film.” The story of “Joliet Jake” Blues (John Belushi) and Elwood Blues (Dan Aykroyd) is about two men who seem to exist for one purpose: to make music within the context of a broader mission. They defy convention. Jake and Elwood are almost mythic figures who, through this movie, have become part of popular consciousness. Their exploits resonate particularly for those who have grown up in the Chicago area. Even the making of the film has become legendary. There are simply too many stories to be told here, but residents of Park Ridge recall the filming. Stories abound of John Belushi and his antics. So to celebrate this history, we look back at how this larger-than-life story came to be…

The Legend of the Blues

“The Blues Brothers” debuted on television– on Saturday Night Live— in April 1978, but they were not manufactured for television in the same way as “The Monkees” were, for instance. The act that was created by John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd was done out of a genuine sense of love for the music– at a time when blues wasn’t in vogue, at least not in the mainstream. Dan, a Canadian-born blues aficionado, has told the story of listening to blues records with John at the 505 Club he operated in Toronto. This was back in 1973, two years before Saturday Night Live debuted. John was in Canada at the time recruiting talent for his National Lampoon Radio Hour. He was more into heavy metal, but he liked the sound of what he was hearing. Dan expected John to know the music since he was from Chicago, after all– Wheaton, to be exact.

Later, when John Belushi was in Oregon shooting National Lampoon’s Animal House, he was further educated in the ways of the blues through local musician Curtis Salgado. At this time, Belushi really got into it. He went all in and learned about blues artists like Robert Johnson. He began to live that life and absorbed as much as he could about the music. (“Curtis” would be the name given to Cab Calloway’s character in the film.)

John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd had become a team in the early days of Saturday Night Live, and they were looking for a new act– something better than playing “killer bees” singing. The two wanted to do something specifically with the blues genre. They already had the look in mind. The black hats, suits and shades were inspired by musician John Lee Hooker. Aykroyd would be the straight man. Belushi was the energetic lead singer. It was Howard Shore, SNL‘s musical director, who suggested they call themselves “The Blues Brothers.” Aykroyd envisioned the team as a warm-up act for the studio audience, but they were such a force, they worked their routine into the live show.

The Blues Brothers were now part of Saturday Night Live history. Although a comedy skit, they were very much serious about the music. They had some legitimate musicians behind them to give them credibility. Dan Aykroyd explained in a later interview that they were not a Delta Blues band (with its more rural associations); they were a “Chicago, electrified urban blues band fueled with the Memphis Stax/Volt movement.” Belushi and SNL house band member Paul Shaffer hand-picked the musicians. They included: Steve “The Colonel” Cropper (lead guitar), Donald “Duck” Dunn (bass guitar), Willie “Too Big” Hall (drums), Tom “Bones” Malone (trombone), “Blue Lou” Marini (saxophone), Matt “Guitar” Murphy (lead guitar), and “Mr. Fabulous” Alan Rubin (trumpet). Shaffer himself played keyboards but was later replaced by Murphy “Murph” Dunne. (Contractual obligations prevented Shaffer from appearing in the film, which did not sit well with Belushi.)

Belushi and Aykroyd were dynamic front men who knew how to put a song over. The two would walk out on stage with Elwood handcuffed to a locked briefcase. Inside was a harmonica. Aykroyd had been playing the mouth harp since he was 17 and was very good at it. And no one could “hot-step” it on stage quite like Elwood. Belushi not only sold each song, but in the words of some of his experienced band mates, he had the timing– and a voice that was better than some headliners.

Belushi and Aykroyd released their debut album, Briefcase Full of Blues, in late November, 1978. (It was recorded live at the Universal Amphitheatre in Los Angeles, where they were opening for comedian Steve Martin.) The album, which later went double platinum, was dedicated to Curtis Salgado. Belushi was already riding high with the release of National Lampoon’s Animal House that summer. When talk turned to bringing the act to the screen, a bidding war broke out amongst the studios. In the end, it was Universal that agreed to make the Blues Brothers movie. Universal studio head Lew Wasserman believed the film could be shot for around $12 million; he was sadly mistaken.

John Landis, who had recently directed Belushi in Animal House, would helm the production and work closely with Aykroyd on the script. Aykroyd had never read a screenplay before much less written one. A typical screenplay is between 120-150 pages; Aykroyd’s tome clocked in at 324 pages! Instead of being written in a traditional way, it had more of a free form style. Included were many descriptive passages as well as specific storylines on how the Blues Brothers were able to recruit each member of the band. There was also a lot of material in there that came directly from experiences Aykroyd had had with his good friend Belushi. They had taken cross country trips together by car, and some of the dialogue– “you’re driving too fast,” “fix the lighter,” etc.– came from those adventures. As a joke, Aykroyd’s draft was bound to look like a phone book. It was up to Landis, an experienced screenwriter, to make some sense of it, which he was able to do after about three weeks.

After three years in an Illinois prison, “Joliet Jake” Blues (John Belushi) is released and reunited with his brother Elwood (Dan Aykroyd). He gets picked up in an old police car– Elwood’s new Bluesmobile. They immediately visit the “Penguin,” Sister Mary Stigmata (Kathleen Freeman), and learn from the nun that their old orphanage needs $5,000 to cover the tax assessment. They also meet up with Curtis (Cab Calloway), their mentor, who steers the boys to Reverend Cleophus James (James Brown). During the church service, Jake has an epiphany. The way to redemption (and to saving the orphanage) will come through their blues band. But getting the band back together and making money the honest way won’t be easy. Since the members had split up, Jake and Elwood must track each of them down. While on their “mission from God,” they are pursued by the police, a crazed woman seeking vengeance (Carrie Fisher), a country band looking to settle accounts, and a group of Illinois Nazis (headed by Henry Gibson). The boys are finally able to get their big gig at the Palace Hotel Ballroom. During the performance, the boys sneak out and race back to Chicago to save the orphanage in time.

A great screenplay can be measured by its complexity or by the sheer delight and fun contained within it. The fact that fans can quote nearly every line of dialogue from the film forty-two years later is a testament to what Landis and Aykroyd were able to achieve. The film was filled with big set pieces, slapstick, and smaller bits of comedic business. As a writer, as imaginative as Aykroyd was, he had a tendency to over-explain things. Fortunately, Landis knew what was unnecessary. One example is the Bluesmobile itself. In order to explain its unique powers to do jumps over cars and back-flips in the air, there was a deleted scene in which Elwood parked the car in a secret location under the “El” in a transformer room– the idea being that this somehow explained what the (charged up) car could do. Landis cut this out with the simple reasoning that it was a “magic car.” And besides, they were on a mission from God, so…

Let the Good Times Roll

The production started even before they had a completed script or a finalized budget. Shooting ran from June 1979 to February 1980. One thing was clear at the outset: the budget would certainly skyrocket. As filming moved into August, there were additional delays with Belushi not being on set. The main reason for the escalating costs, however, was simply due to the epic scale of the action.

The Blues Brothers was shot in and around the Chicago area, including Park Ridge. When Elwood drives through the yellow light, moviegoers will notice the Nelson Funeral Home and the gas station across the street, both of which still stand today. When the brothers are later pursued by the police, fans will also recognize the intersection of Talcott and Courtland. One friend I’ve spoken to remembers the film shoot in South Park by Devon and Cumberland– and John Belushi relieving himself in an alley!

John and Dan with Carrie Fisher

The Blues Brothers famously makes use of the Dixie Square Mall in Harvey, Illinois. At the time of production, the mall had been closed for a year. The filmmakers had to renovate the facility and create store fronts for the car chase in which Jake and Elwood are chased by the same police. Dan Aykroyd took particular delight in bringing life to this abandoned shopping plaza. It was another expensive undertaking, but the money would be there on the screen. It was during the making of this sequence that John Belushi disappeared one evening. Aykroyd tells the story of following his trail into the surrounding neighborhood late one night. John had invited himself into a neighbor’s house and proceeded to make himself at home. Anxious to start shooting again, Dan found John flaked out on a couch. “You’re here for John Belushi, aren’t you?” the homeowner asked. Dan was able to rouse him and get him back to the set.

The most famous location, of course, are the scenes shot in downtown Chicago, particularly the car chase through Lower Wacker Drive, which culminates in a drive through Daley Plaza. None of this would have been possible without the cooperation of Mayor Jane Byrne. (She agreed on the condition that Belushi and Aykroyd donate $50,000 to charity.) This was the first major film shot in Chicago in many years. Mayor Richard J. Daley had essentially banned filmmaking in the city. According to John Landis, it was because there was an old episode of M Squad shot in Chicago in which Lee Marvin’s police detective accepted a bribe.

The Chicago scenes were shot early Sunday mornings when they could block off the streets. Production assistants were at every corner to ensure no one would be killed with vehicles traveling at 118 mph. The climactic car chase and the pursuit into City Hall accounted for some of the largest expenditures, both in terms of money and personnel. Some of the unofficial numbers of what was needed included 60 Illinois State Police cars, 42 Chicago cop cars, 17 ambulances, 200 National Guardsmen, 60 Chicago cops, 400 troops, 15 horses, 3 Sherman tanks, 3 helicopters, 3 fire engines… and so on. The film embraced excess, and one can only imagine the reaction from Universal execs on being told that 103 cars would be wrecked or that a helicopter would drop a Ford Pinto 1,200 feet in the air.

The Blues Brothers is a visual record of a time and place that no longer exists. We see areas of Chicago and the suburbs that are long gone or markedly different. One of the best examples is Chicago’s famed Maxwell Street and its marketplace. It still exists, of course, albeit in a cleaned-up, redeveloped version. But The Blues Brothers shows the old Maxwell Street as it was. Actor Henry Gibson, in an interview, talks about how the film catches “the rhythms of life in the city,” and the times. This certainly can be applied to its evocation of old Maxwell Street. (There is additional footage of Maxwell Street seen in the Extended Version of the film.)

Besides the action set pieces that proved expensive, The Blues Brothers was overflowing with cameos, which included Henry Gibson (head Nazi), John Candy (Jake’s parole officer), Steve Lawrence (booking agent Maury Sline), Twiggy (the girl at the gas station whom Elwood tries to proposition), Frank Oz (corrections officer), and Steven Spielberg as the Cook County Clerk. The suits at Universal were balking, wondering why it was necessary to include stars like Twiggy.

The sheer size of the production was unprecedented for a comedy. The re-adjusted budget was expanded to $17.5 million, but eventually it grew to $27 million. Universal execs were nervous for a variety of reasons. Belushi’s 1941, directed by Steven Spielberg, proved to be a flop at the box office. The most nervous man at Universal was studio head Lew Wasserman, who kept close tabs on the production on a daily basis and constantly looked for ways to speed things up. For him, this was proving to be one long fiasco.

It was a minor miracle that John Belushi survived the production. It’s impossible to talk about The Blues Brothers without mentioning the amount of drugs being consumed on the set. It was 1979, and many stars at that time were either into it or experimenting with it. But Belushi’s addiction to cocaine was legendary in how extreme it was. People wanted to “do a line” with John, and he was surrounded by enablers. Coke would be brought in to him in suitcases, and security would look the other way. A mountain of the substance would be piled on a table in his trailer. Landis later recalled one time when he tried to flush it all down the toilet. There was a small skirmish with Belushi, who broke down and admitted he had a problem that would probably kill him.

Belushi was out of control. In a perfect world, he should have gone into rehab then, but there was the pressure of finishing the film. Universal was burning through money, and an irate Wasserman was monitoring the overruns. Certainly no one was going to shut the film down– unless Belushi died on the scene. A lot of his erratic behavior was clearly fueled by his addiction. At one point, a bodyguard was brought in to try and control John. But it wasn’t until the production left Chicago and returned to Los Angeles for completion that Belushi was able to stick closer to the schedule. Things ran a little more smoothly towards the end– although not totally without incident. Prior to filming the Palace Hotel Ballroom scenes at the Hollywood Palladium, Belushi injured his knee when he attempted to ride a kid’s skateboard. A lot of anesthetics got him through the performance.

Fans remember those big sequences that ran up the budget– the car chases and the Chicago City Hall climax– but the film is equally embraced for its smaller moments, some of which are just too bizarre, like Elwood being fascinated by the toaster in Ray’s Music Exchange. Or they remember Elwood’s Dragnet-like delivery of his lines, as when he’s asked if they are police. “No, ma’am. We’re musicians.” It’s the acting of these two comedy pros that give the film resonance. Underneath the guise is talent. Despite the drama and the drugs, Belushi was a comic genius who was loved for his ability as an actor as well as his generosity as a human being. When he takes off those sunglasses, all is forgiven.

The Blues Brothers is in one sense disconnected from reality. Things happen that can’t be logically explained. The film is essentially a musician’s tall tale with everything exaggerated and given ridiculous scope; for instance, the great military forces pursuing these two petty criminals. “Comic impossibility” is another way of describing a film not intended to be serious drama.

One sequence in particular has a heightened sense of unreality. Jake and Elwood have driven to a hotel for transients in the city. The strangeness begins with Carrie Fisher’s calm malevolence. Her character pulls up in a car and fires a bazooka at the brothers. Arising from the debris, they quietly shrug off the assassination attempt and proceed to make their way up the steps. There’s a weird vibe hovering over this landscape. It’s a men-only hotel filled with froggy-voiced attendants who watch wrestling matches on TV and card-playing old-timers who demand their Cheez Whiz. A policeman had been in earlier and left his business card. Elwood silently inspects it up close before handing it to Jake. He reads it without saying a word and flicks it away indifferently. The men in black are detached from the normal world but oddly at home here. Their comically-narrow room looks out onto an elevated train. The scene has one of the more touching moments in the film where Elwood drapes a blanket over Jake after he falls asleep on the cot. Louis Jordan’s “Let the Good Times Roll” plays on the phonograph. The following morning, Carrie Fisher returns but with the police arriving at practically the same time. She detonates the building right at the point when the police break into Elwood’s room. But again, the brothers emerge unscathed from underneath a pile of bricks. They proceed on their mission.

At the same time, there is a grittiness to this lunacy, an urban realism: the crowded Maxwell Street, the soiled white shirts, the newspapers blowing across a city alley. The opening credits over the industrial areas of Chicago make the point clear. It’s a visual link to the lower and working classes that first gave a voice to soul music. The Blues Brothers is not a clean, glossy musical like the old MGM films. It’s very much of the city. And this is 1980s South Side Chicago.

Although viewed as a comedy, the film works just as well, if not better, as a musical. Throughout the story, Landis incorporated all types of songs, from those that are performed on stage (at the ballroom) to those that advance the story (Aretha Franklin’s “Think.” ) There are also the tracks played over the scenes, like Fats Domino’s “I’m Walkin'” during the sequence in which the brothers are promoting their concert. Besides Aretha Franklin’s song, some of the other highlights include “Shake a Tail Feather” (Ray Charles), “Minnie the Moocher” (Cab Calloway), and Belushi’s own version of “Jailhouse Rock.” Throughout the film, there are many tributes to other artists. “Sweet Home Chicago” is itself an homage to the late Robert Johnson. Most of the stars performed to playback, in which they lip-synced their songs on stage. However, this was especially difficult for Aretha Franklin, who never sang a song twice the same way. James Brown, on the other hand, performed live as did John Lee Hooker.

Belushi and Aykroyd with John Lee Hooker

At the preview, The Blues Brothers ran two and a half hours and contained an intermission– a true comedy epic. Landis would cut 20 minutes by the time it went into general release. In 1980, major films typically opened in about 1,400 theatres. The Blues Brothers opened in less than half that number. Universal assumed it would bomb and held it back. And there was the race issue. One LA theatre exhibitor, in particular, didn’t want the film opening in white areas because of the expected black crowds that would come. There was also concern whether white audiences would go see a film with black performers who weren’t even in vogue at the time.

Despite these controversies and misjudgments, The Blues Brothers became a hit at the box office, ultimately taking in $115 million. Audiences loved it. John Landis himself made the rounds in Chicago to gauge the reaction. The film was shown in 4-track mag stereo in some theatres, so the experience would have been something special. At the Chicago Theatre, for example, moviegoers went wild, especially black audiences who were seeing these music legends on the big screen. Except for Ray Charles, who was still working, the film was a comeback for many of the artists depicted in the film. Whether black or white, audiences could relate to Jake and Elwood. As far as “criminals” go, they were pretty decent guys, men in black who were up against “the man,” the system, the cops… And when they literally drove the embodiment of hate over a bridge and into the water, the crowds cheered.

For suburban white boys growing up in the 1980s, The Blues Brothers was an introduction to blues music and artists like Aretha Franklin and Cab Calloway– and even black culture in general. The music from The Blues Brothers stays with you and invites you to discovery. You want to learn more about it, search it out, even play it. That’s what audiences should take away from the film. Cab Calloway, when asked to perform “Minnie the Moocher,” had wanted to do a disco version of his trademark song– in keeping with current trends. But John Landis, to his credit, wanted the original version because it was great, and that’s what makes The Blues Brothers great. It never pandered to popular trends in music. It went backward in time and took its audiences with it and re-introduced them to the master blues men of old.

Cab Calloway sings “Minnie the Moocher.”

The Blues Plays On

Many grew up seeing the film on television in the 1980s. Chicago’s WGN-TV often played it, and for those viewers who have only seen it on television, they will be surprised at the rather salty dialogue. In retrospect, it could be argued the F-bombs were probably unnecessary given the overall tone of the film. There’s no sex or violence, and this is a film, after all, where Jake calls Elwood a “Motorhead”– terminology more suggestive of the PG film it could have been. In its defense, however, the film’s voice has a streetwise edge to it that makes the characters ring true. When Cab drops the N word, you know this isn’t The Sound of Music. The language is faithful to the time and place. Situations may have a comic book tone, but these are characters who also represent (and stand up for)– in an unstated way– the transients and the orphans of society. In short, Jake and Elwood are true to the unglamorous things that shaped the blues in the first place.

Despite the language in spots– and its depiction of Sister Stigmata– The Blues Brothers somehow made it onto the Catholic Church’s list of recommended films! According to the Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano, it is viewed as being a Catholic classic. For those on the fence about coming out to the Pickwick for an R-Rated film, we shall quote Jake by saying, “What we’re asking you to do is a holy thing.”

But behind the laughter is the sadness in knowing that John Belushi died in 1982 from a drug overdose. One of the great comedy actors left this world all too soon. He and Aykroyd had made a terrific comedy team, and it’s fascinating to think of all the films they could have gone on to make together. How much better a film like Ghostbusters (1984) could have been as an Aykroyd and Belushi vehicle. In 1998, there was an ill-conceived sequel to The Blues Brothers called Blues Brothers 2000. The film had Aykroyd returning but now paired with a new lead singer played by John Goodman. The film was a disaster and failed with both audiences and critics. It was directed by John Landis, whose career had essentially died– at least creatively– after Trading Places (1983).

It’s been 42 years since The Blues Brothers came out. Society has changed a great deal. We live in a world of senseless violence and social unrest, war and political discord. There are few things that bring people together in 2022, but music can be one of them. Music unites people of all colors, of all generations. If they were together now, Jake and Elwood’s message would be all about spreading the music– and how those shared experiences unite us. As long as the band played, all would be right in the world…

Dan Aykroyd, along with John’s brother Jim, are still sharing that love around the country, taking the blues on the road. The popular House of Blues thrives. Last New Year’s Eve, there was Dan and Jim performing in Chicago. But back in 1978 during the live concert in Los Angeles, Elwood opened by telling audiences that “by the year 2006,” the music known as the blues will exist only in your classical record department of your public library. Time has proven otherwise. Through their efforts, the revival continues.

~MCH

For more about the making of The Blues Brothers, check out this Vanity Fair article from January 2013 by Ned Zeman: Click Here!

For more about the shooting locations of The Blues Brothers, Click Here!

Original trailer…

The Chicago Bluesmobile is coming to Park Ridge! The most famous Dodge Monaco in the world will be parked outside the Pickwick Theatre on the night of our show. The World Famous Chicago Bluesmobile Is The One and ONLY Genuine, No Imitation, “Official Bluesmobile of Chicago,” As Recognized By Blues Brothers Approved Ventures.