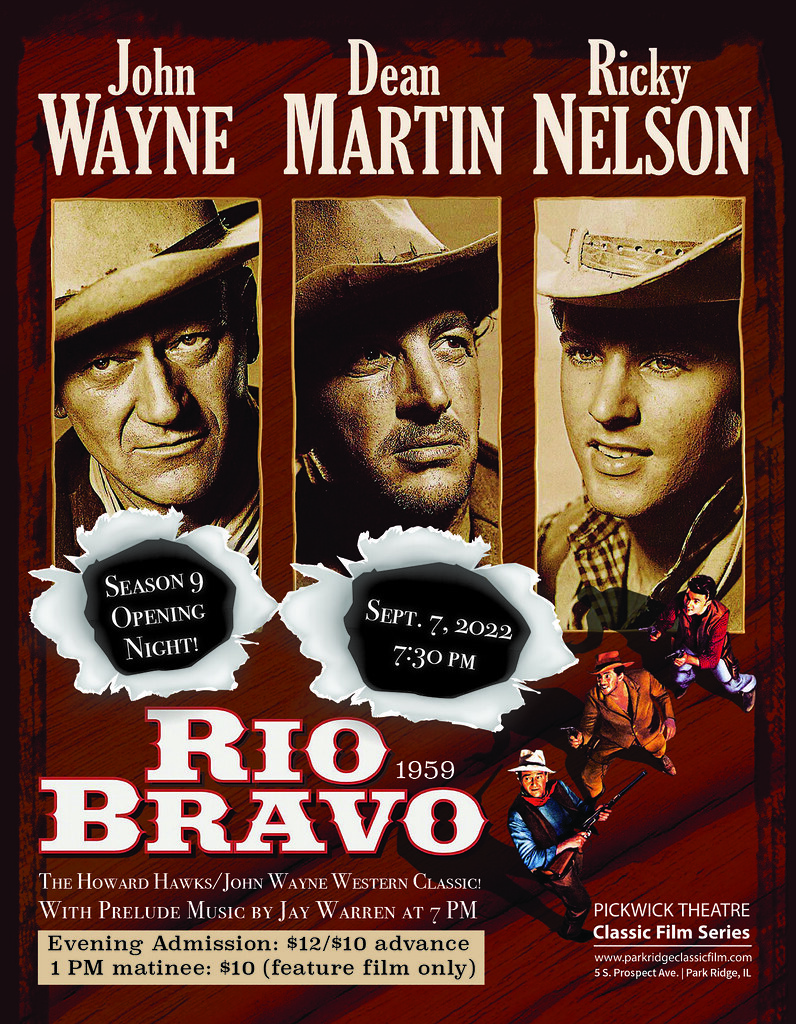

WHAT: Rio Bravo (1959, DCP) Opening Night!

WHEN: September 7, 2022 1 PM & 7:30 PM

WHERE: Pickwick Theatre, 5 S. Prospect Ave, Park Ridge, IL

WHAT ELSE: Pre-show music by organist Jay Warren at 7 PM; trailers

HOW MUCH: $12/$10 (advance) or $10 for the 1 PM matinee

For Advance Tickets: Click Here!

“I saw ‘High Noon’ at about the same time I saw another western picture, and we were talking about western pictures and they asked me if I liked it, and I said, ‘Not particularly.'” ~Howard Hawks

Rio Bravo (1959) was director Howard Hawks’ response to High Noon (1952). Although he may have admired the earlier film’s artistic qualities and was certainly a fan of Gary Cooper (who had starred in Hawks’ 1941 Sergeant York), he did not appreciate the film’s values. In Hawks’ view, it was ridiculous for a marshal (Cooper’s Will Kane) to be going around town begging for help from non-professionals– only to be saved by his Quaker wife. John Wayne was in accord with this view. The Duke never cared much for the politics of the people behind High Noon, particularly writer Carl Foreman. And he never appreciated Gary Cooper tossing his badge onto the ground at the end of the movie.

Rio Bravo is about respecting that badge– and the professionals behind it. It’s a movie about finding the courage to do one’s job– and do it well.

The Hawks hero was always a professional. John Wayne as John T. Chance.

Pat Wheeler: A game-legged old man and a drunk. That’s all you got?

John T. Chance: That’s WHAT I got.

The Pickwick Theatre Classic Film Series returns for its ninth season with this special screening of Rio Bravo— certainly one of Howard Hawks’ best films and one of the greatest Westerns ever made. The film was hugely successful in 1959 and remains influential today. Many filmmakers have been inspired by it, including John Carpenter, whose Assault on Precinct 13 (1976) updated the basic premise, Peter Bogdanovich, Walter Hill, and Quentin Tarantino, who once famously said– when beginning a new relationship with a girl– if she doesn’t like Rio Bravo then there’s no relationship!

The film represents everything that made Howard Hawks one of Hollywood’s greatest filmmakers even though he never won a competitive Oscar. Hawks shunned self-importance and his only nomination was for Sergeant York. His camera was very functional and he approached film-making like the engineer he was. His often-quoted maxim was, “A good movie is three good scenes and no bad scenes.” He made films in every genre, and one of his most recurring themes involved male bonding. Even when he was repeating himself in later years with 1966’s El Dorado and 1970’s Rio Lobo (variations of Rio Bravo), he was still infinitely more entertaining than most other directors of the era.

Rio Bravo was Hawks’ first film in four years– his last, The Land of the Pharaohs (1955), being one of his weakest. For star John Wayne, this was a return to the genre he would always be associated with. His last Western, John Ford’s The Searchers (1956), is widely regarded as one of the finest ever made, but The Duke had been less successful in the films that followed it. Nevertheless, he remained one of the most popular actors in Hollywood.

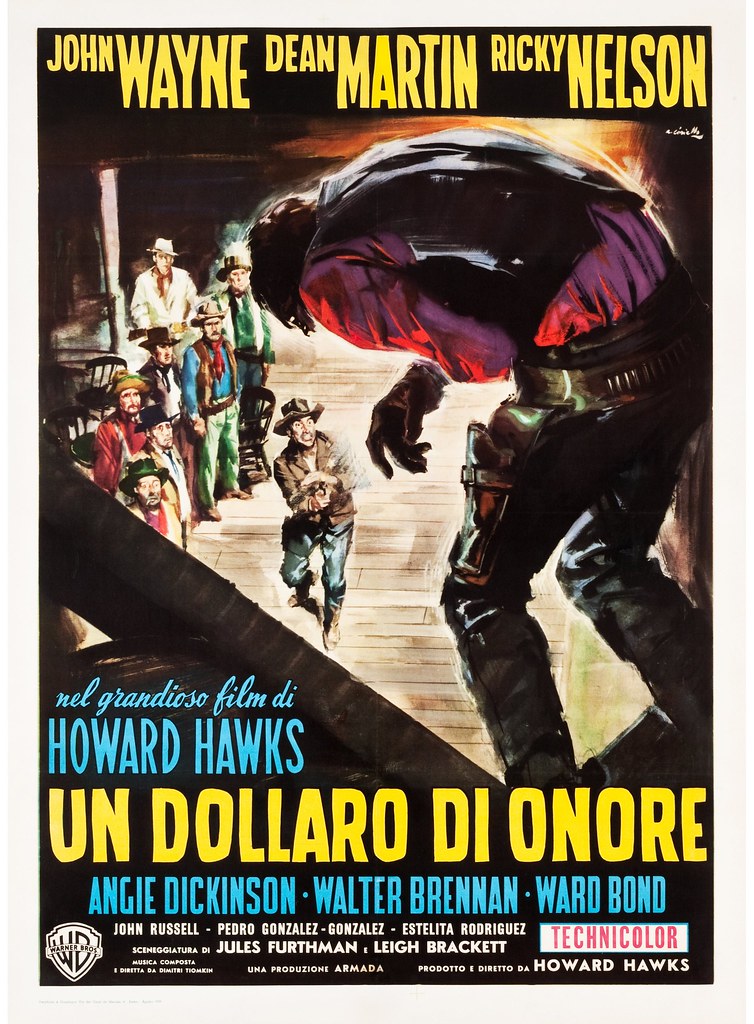

In Rio Bravo, John Wayne stars as John T. Chance, a sheriff determined to keep an outlaw locked in jail with his town under siege. Chance’s only help is a drunk (Dean Martin) and an old, ill-tempered “cripple” (Walter Brennan). Ricky Nelson plays Colorado, the young gun who casts his lot with Chance, and Angie Dickinson is the flirtatious Feathers, a girl with a past who cares deeply for the sheriff.

The short story the film is based on is credited to B.H. McCampbell, but Hawks’ biographer Todd McCarthy has pointed out that this was in fact Hawks’ eldest daughter, Barbara Hawks McCampbell. The screenplay, which offers sharp, witty dialogue, was written by two Hawks’ stalwarts, Jules Furthman and Leigh Brackett. They excelled at good movie writing. One of their most well-known collaborations was on Hawks’ The Big Sleep (1946), which was written with William Faulkner. In addition to working with Hawks, the Chicago-born Furthman had written eight Joseph Von Sternberg screenplays; curiously, his brother Charles was credited with the screenplay for Von Sternberg’s Underworld (1927), a film that features a character named “Feathers.” Brackett, on the other hand, was a noted science fiction writer and became famous to a whole new generation as one of the writers on George Lucas’ The Empire Strikes Back (1980), a film released two years after Brackett’s death.

Rio Bravo is episodic and is driven by the characters, not by the plot. Although the group dynamic is essential, it is Dean Martin’s story arc that is the central theme. The story centers around his journey towards redemption and how he comes back to the fold. “Dude” is a drunk, but he used to be Chance’s trusted deputy. Can he become a professional once again? This is the conflict at the center of everything else that is unfolding.

The narrative structure is a reflection of what was going on in television Westerns at the time. Hawks picked up on this when he returned to America after living in Europe for several years. He immediately noticed how audiences were drawn to familiar characters each week. The impact of television, particularly the Western format, made its imprint on the film. Additionally, several actors in Rio Bravo were working in the new medium. A third of all prime-time television shows were Westerns, and actors like Walter Brennan (“The Real McCoys”) and Ward Bond (“Wagon Train”) could be seen each week and were already familiar to most audiences.

When it came to casting, Montgomery Clift turned down the role of Dude but supposedly suggested Dean Martin, whom he had co-starred with in The Young Lions (1958). It was Martin’s agent who contacted Hawks about the role. He landed the part because Hawks was impressed with his determination; Dino had flown in on a private plane for an early morning interview with the director after a late performance in Las Vegas. If Martin was willing to do that, Hawks knew he wouldn’t let him down in the movie. At this point in Martin’s solo career, The Young Lions had not yet been released, so he was still viewed as a bit of an unknown when it came to serious drama. Martin, however, did not disappoint and gives an honest and moving performance. In the late 1950s, he still took acting seriously– and it shows. It’s a far cry from the lazy, “nightclub drunk” schtick he would do in later decades, particularly on his television show.

A lesson in bravery– and reclaiming one’s dignity. The alcoholic pours the liquor back into the bottle.

The 26-year-old Angie Dickinson was a relative newcomer to the movie business and was cast after Hawks had seen her in an episode of “Perry Mason.” She fits into the mold of the classic Hawks female, embodied by actresses like Lauren Bacall. She’s on the fringe of the male group, but she’s independent and sets her own standards. The Bacall influence is evident. In fact, one of her famous lines in the movie is actually lifted from Bacall in Hawks’ To Have and Have Not (1944). It’s a slight variation of Slim’s line after kissing Steve: “It’s even better when you help.”

For the role of Colorado, Hawks initially wanted Elvis Presley, and it’s easy to see him in the part. However, Presley’s manager, Colonel Parker, demanded too much, including top billing, which wasn’t going to work with John Wayne. In place of Elvis, they cast teen idol Ricky Nelson, who had risen to fame on his TV show, “The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet.” Nelson’s father was a friend of Hawks and this undoubtedly led to the idea of him being cast. Nelson didn’t embarrass himself in the part, and his name certainly didn’t hurt at the box office. In fact, a lot of teens and pre-teens went to see this film solely because Ricky Nelson was in it.

The rest of the cast was rounded out by venerable character actors like Walter Brennan, who had starred in Hawks’ other great Western, Red River (1948), and Ward Bond. (This was Bond’s 22nd film with John Wayne.) Others in the cast included John Russell as Nathan Burdette, Pedro Gonzalez-Gonzalez as Carlos, Claude Atkins as Joe Burdette, and Bing Russell (father of Kurt) as the cowboy who gets killed at the beginning of the film.

Rio Bravo was shot outside Tucson, Arizona, at what is known as the Old Tucson Studios. This location, which evoked the old Southwest with its adobe ruins, had been built in 1939 and was used for many Westerns including Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957). The filming, which began on May 1, 1958, was a happy experience for all involved, although when the cast celebrated Ricky Nelson’s 18th birthday a week into shooting, the Duke and Dean Martin deposited him in a 300-pound sack of steer manure as part of his initiation.

There is a scene late in the film in which the crooner (Martin) and the teen idol (Nelson) sing a couple songs together. Although it may sound out of place to someone who hasn’t seen the film, it’s a nice moment that fits the scene. Here, the unity of the group is celebrated through song. One of the songs, “Cindy,” Nelson sang on “The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet.” Even Walter Brennan gets in on the act. Fortunately for all involved, John Wayne does not sing.

Although over two hours, Rio Bravo is not an epic Western like the John Ford films set in Monument Valley or even Hawks’ own Red River. It’s a street Western that is more intimate in its details of the town and its people. The film has a leisurely, stately pace that allows audiences the opportunity to get to know the characters– and these are characters you want to know. It’s a far cry from contemporary (mainstream) cinema that inundates you with noisy action and non-stop visuals for over two hours. However, there are certainly glorious action sequences– it is a Western after all.

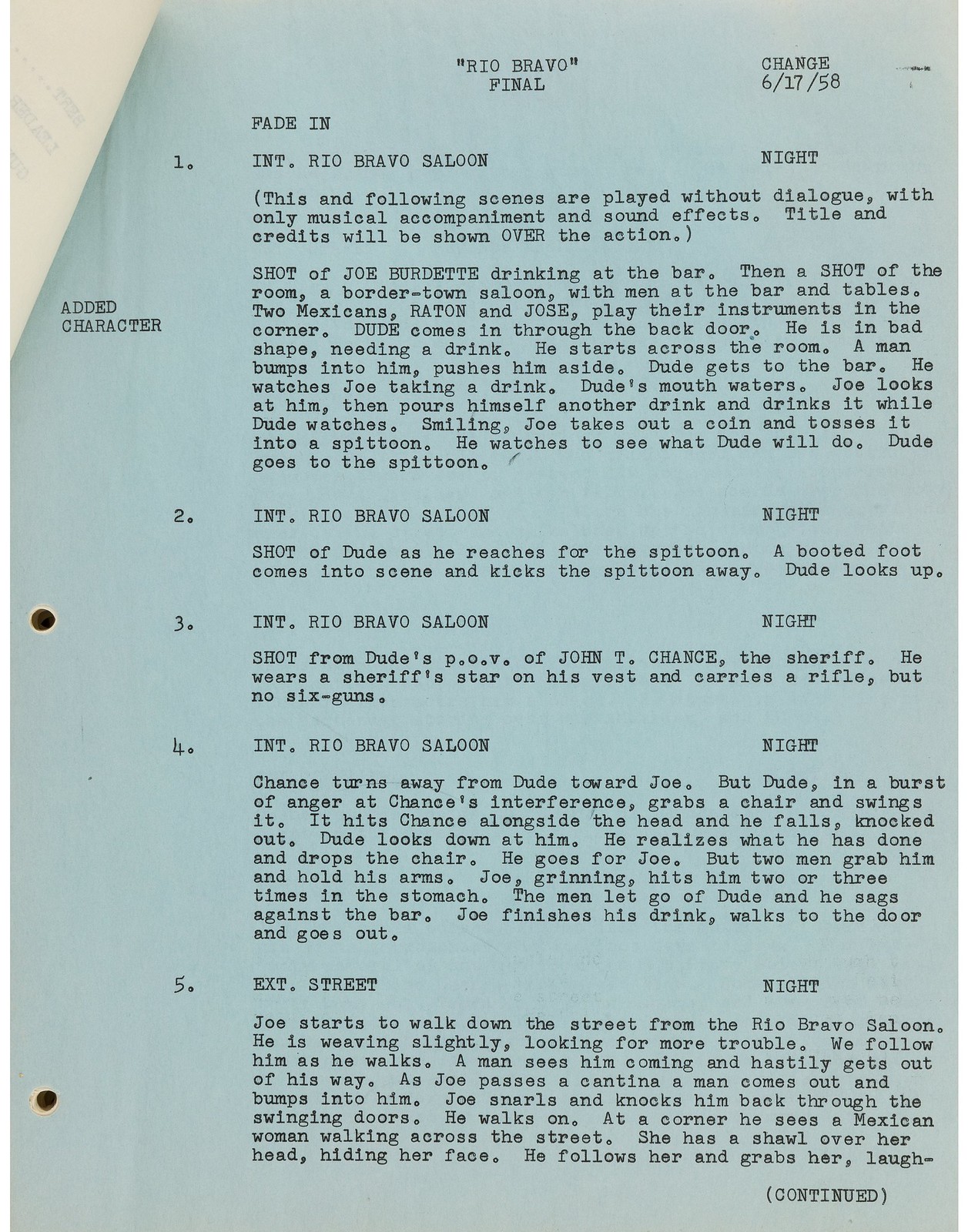

One of the most unique sequences is the opening, which recalls the silent film tradition Hawks knew so well. The first four minutes, depicting Dean Martin being humiliated in a bar and the ensuing killing by outlaw Joe Burdette, is all done without dialogue. And it sets up the subplots for the rest of the film. The first scene is so strange because it opens in medias res. Aside from the opening credits depicting a wagon train, there’s no establishing shot of the town or an outdoors setting. The audience simply sees a door opening and Dude quietly walking in.

Though filming was completed in 1958, Rio Bravo opened on March 18, 1959. It was one of the most successful films of the year– the third highest-grossing film of the year– but its critical recognition would come later, beginning in France. It is here where many American directors, especially Howard Hawks, came to the attention of the auteur film critics.

Howard Hawks and John Wayne shaped our perception of the Old West. Wayne made a career out of creating a legend. It was the image of how a man should act. “Sorry don’t get it done, Dude,” sums it up pretty well. He was a moral force in his films– attributes that continue to inspire in the 21st century. The Duke’s image has sometimes been misappropriated in the years after his death, but it’s one that continues to define our memories of the Hollywood Western.

Rio Bravo remains Hawks’ most personal project because of its viewpoint. He was responding directly to a film (High Noon) that violated his own idea of ethical conduct. Although not as famous as High Noon, Rio Bravo is the one we chose to open our ninth season at the Pickwick Theatre. The film plays great to a large audience. Moviegoers always seem to respond to the humor and chemistry of the performances on display.

~MCH