WHAT: Meet Me in St. Louis (1944, DCP)

WHEN: December 14, 2022 1 PM & 7:30 PM

WHERE: Pickwick Theatre, Park Ridge, IL

WHAT ELSE: Introduction by Chicago Tribune film critic Michael Phillips; pre-show organ music by Jay Warren at 7 PM; cartoon

HOW MUCH: $12/$10 advance or $10 for the 1 PM matinee

Advance Tickets: Click Here!

Meet Me in St. Louis (1944) is one of the best-loved musicals of all-time and a perennial holiday classic– due in no small measure to Judy’s Garland’s memorable rendition of “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas.” For a generation of classic movie lovers in the Chicago area, the film is fondly remembered as one of the classics often played on television. Long before there was ever a “TCM,” there was “Family Classics” on WGN-TV, where so many fans experienced these films for the first time. Meet Me in St. Louis has much to offer, but its overall success can be attributable to three main individuals: producer Arthur Freed, director Vincente Minnelli and star Judy Garland.

Lyricist-turned-producer Arthur Freed had been an associate producer on The Wizard of Oz (1939). He worked with Judy Garland again in the popular musicals he produced that paired her with Mickey Rooney, including Babes in Arms (1939) and Strike Up the Band (1940). In 1942, Freed had come across the stories of Sally Smith Benson. Her sentimental vignettes about life in St. Louis appeared in The New Yorker magazine under the title 5135 Kensington. The original eight vignettes– along with four new ones– would form the basis of her novel, Meet Me in St. Louis. The stories told of her happy childhood around the time of the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exhibition– better known as the St. Louis World’s Fair. Freed believed the Benson stories could be adapted into a musical for Judy Garland.

For Arthur Freed, these nostalgic tales took him back to his own childhood in Charleston, South Carolina, where he grew up in a large family. For many in the country, it was a time to be looking back on happier times. In 1944, the world was still at war and Americans were reading about and listening to the many casualties overseas. Meet Me in St. Louis would be a film about family and home– the very things America was fighting for at the time.

Although the year 1904 is quite distant to 2022 audiences who might not understand why a family would get excited over a “long-distance” phone call during dinner, the turn-of-the-century events depicted were only forty years removed for 1940s audiences. Most moviegoers at that time would have remembered the era, if not the exact time and place. For Freed, Meet Me in St. Louis would mimic a popular theme from Judy Garland’s most memorable film, The Wizard of Oz: there’s no place like home.

The basic story recalled aspects of the Broadway play Life with Father, a property that Freed unsuccessfully tried to acquire. The popularity of the play, set during the turn of the century with its nostalgic qualities centering on family, greatly influenced Freed to develop Meet Me in St. Louis. To help translate the story to the screen, author Sally Benson herself was enlisted and contributed a screenplay, but this was not used. The problem with Benson’s original stories was that there was no real plot to them. William Ludwig, who had worked on the Andy Hardy films, was brought in and introduced the romance angle. But it was still not quite right. Ultimately, the final screenplay would be credited to Irving Brecher and Fred Finklehoffe.

Beginning in the summer of 1903, the story follows the lives of the Smith family through the seasons as they eagerly anticipate the St. Louis World’s Fair. This upper middle class family comprises father Alonzo Smith; his wife Anna; the four daughters, Rose, Esther, Agnes and Tootie; and son Lon Jr. There is also Grandpa and Katie the maid. But the Fair is not the only thing the family looks forward to. There is also the anticipated marriage proposal for Rose– as well as a boy-next-door romance between Esther and neighbor John Truett. However, their lives are adversely affected when Alonzo makes a sudden announcement that the family will have to move to New York due to his promotion at the law firm.

In the eyes of studio head Louis B. Mayer, the real tragedy he saw in the story was that the family would be missing the Fair! (In real life, they did.) From the beginning, Judy Garland was slated to star. However, she had misgivings about the role. Now that she was 21 years old, she did not want to play another “juvenile.” Only recently had she finally transitioned to more adult roles. She wanted nothing to do with the part of Esther. When she reluctantly accepted, she didn’t take the role seriously at all. It would be the film’s director who would convince her otherwise.

For Meet Me in St. Louis, Arthur Freed had initially sought director George Cukor, whose war-time commitments precluded his participation. Consequently, Freed enlisted the Chicago-born Vincente Minnelli, and it could not have been a better choice. Minnelli’s first significant film for MGM had been Cabin in the Sky (1940), produced by Freed and featuring an all-black cast. It was Minnelli who convinced Judy Garland of the value of her role and of the film itself. He made her take it seriously, and as a result, she would give one of her finest performances. She would later say that she never felt more lovely than she did in this film with the way Minnelli framed her on-screen. Under his guidance, she blossomed as a star performer. In fact, the two fell in love during the making of this picture and would later marry shortly after its completion.

But it was more than Minnelli’s handling and photographing of Judy Garland that made Meet Me in St. Louis such a beautiful film. It was his eye for detail, the evocative lighting, and the staging of the scenes. Though Sally Benson’s contributions to the final screenplay were limited, Minnelli did consult her on all the minutia surrounding her life in St. Louis. Minnelli’s own background had been in set and costume design. As a result, the film is a remarkable example of period detail and authenticity, particularly in costuming and in the decor of the Smith home. (The homes seen in the film were actually built on Backlot 3 in Culver City; the middle-America neighborhood set would appear in later film and TV productions, notably The Twilight Zone‘s “Walking Distance.”)

The film was shot in Technicolor by cinematographer George J. Folsey, whose career in movies spanned nearly sixty years. He had photographed two Marx Brothers films (The Cocoanuts, Animal Crackers) as well as later classics like Seven Brides For Seven Brothers and Forbidden Planet. During the course of his career, he would be nominated thirteen times for Best Cinematography but never won. Meet Me in St. Louis displays some of his best work. Particularly noteworthy is the scene with Esther and John Truett dimming the lights in the Smith house. It was choreographed by Minnelli in one uninterrupted shot. It proved to be one of the most difficult sequences to film given the fact that the lighting changes continuously throughout the scene.

Vincente Minnelli was adept at handling actors, and Meet Me in St. Louis features a stellar ensemble cast. Though Judy Garland was the star, Meet Me in St. Louis is equally well-known for the performance given by 7-year-old Margaret O’Brien as Tootie Smith (based on Sally Benson herself). Modern viewers who go in expecting grating sentimentality or cloying sweetness from this juvenile performer might be surprised by her, at least in regards to this film. Besides holding her own in her scenes with Judy, O’Brien brings certain tonal qualities that make the film more interesting and more real. It’s a role that could’ve offered only pap, but that’s not the case here.

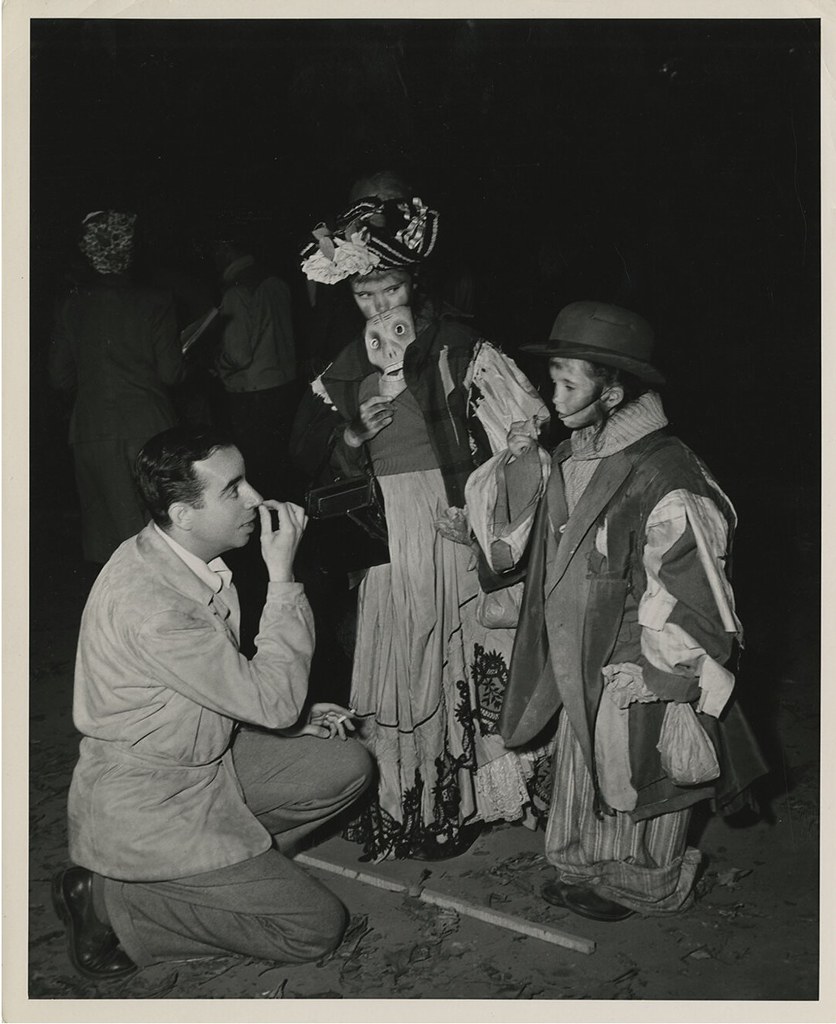

If not outright darkness, O’Brien’s Tootie does exude real-life anxieties that children in the real world face. One of the most magical sequences in the film is the Halloween scene. Not only is it a fascinating look back at the tradition of Halloween and how it used to be– the good ol’ days of kids making bonfires in the streets!– but the sequence also captures the need to be accepted and done through a child’s perspective. This rite of passage is one of the most sinister yet rewarding moments in the entire film, and it’s carried completely by Margaret O’Brien.

Vincente Minnelli gives Margaret O’Brien some direction for the Halloween sequence…

Joan Carroll and Margaret O’Brien on Halloween night…

Also in the cast is stalwart Leon Ames as Alonzo Smith, Mary Astor as Mary Smith, newcomer (and Freed protege) Lucille Bremer as eldest sister Rose, Tom Drake as John Truett, the great character actress Marjorie Main as Katie, Harry Davenport (Grandpa), June Lockhart (Lucille Ballard), Henry Daniels, Jr. (Lon Smith), Joan Carroll (Agnes Smith), and Hugh Marlowe in a small role as Colonel Darly, a suitor of Rose.

The film’s score was adapted by Roger Edens and featured several songs faithful to the period in which the film is set, such as the popular “Meet Me in St. Louis,” which dated back to 1904. The newer songs were composed by Hugh Martin and Ralph Blane. Most famously, there was “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas,” which originally had much darker lyrics that Judy Garland refused to sing. The lines originally went, “Have yourself a merry little Christmas/It may be your last/Next year we may all be living in the past.” Wisely, the songwriting team changed these lyrics for Judy and the rest is history.

The next celebrated song– although it actually ranks higher on the AFI’s “100 Years… 100 Songs” list– is “The Trolley Song,” which Judy performs on a moving trolley on her way to the fairgrounds (courtesy of some process shots). Freed had wanted a song about the trolley, not just a song set on a trolley. Originally, this sequence led directly to a love scene taking place at the construction site for the Exposition. Rogers and Hammerstein’s “Boys and Girls Like You and Me“– a song cut from their Oklahoma!— was incorporated into the scene between Esther and John. However, it was felt that this slowed the movie down too much. Its inclusion was unnecessary given that Esther had already sung “The Boy Next Door.” In the case of the latter, that particular song moved the plot forward. With the deleted Rogers and Hammerstein song, it was felt that it merely commented on things the audience already knew. The recording of the song still exists, but the footage itself is lost.

The deleted scene with the Fair under construction…

Meet Me in St. Louis had a budget of nearly two million dollars. It was shot from December 1943 until April 1944. The production spanned 70 days, which was a long shoot for its day, but several of the delays were brought about due to various illnesses on the set. Aside from other delays related to Judy’s insecurities as an actress– sometimes skipping out on rehearsals– it was generally a very pleasant set for all involved. Cast members would fondly recall its production and the lack of difficulties in its making. Though Judy Garland may have been concerned about Margaret O’Brien’s welfare and work schedule possibly mirroring her own, those fears were never realized. O’Brien went on to have a solid career, but more importantly, a stable life. To this day, Margaret O’Brien continues to make personal appearances and share her memories of working on the film with her legendary co-star.

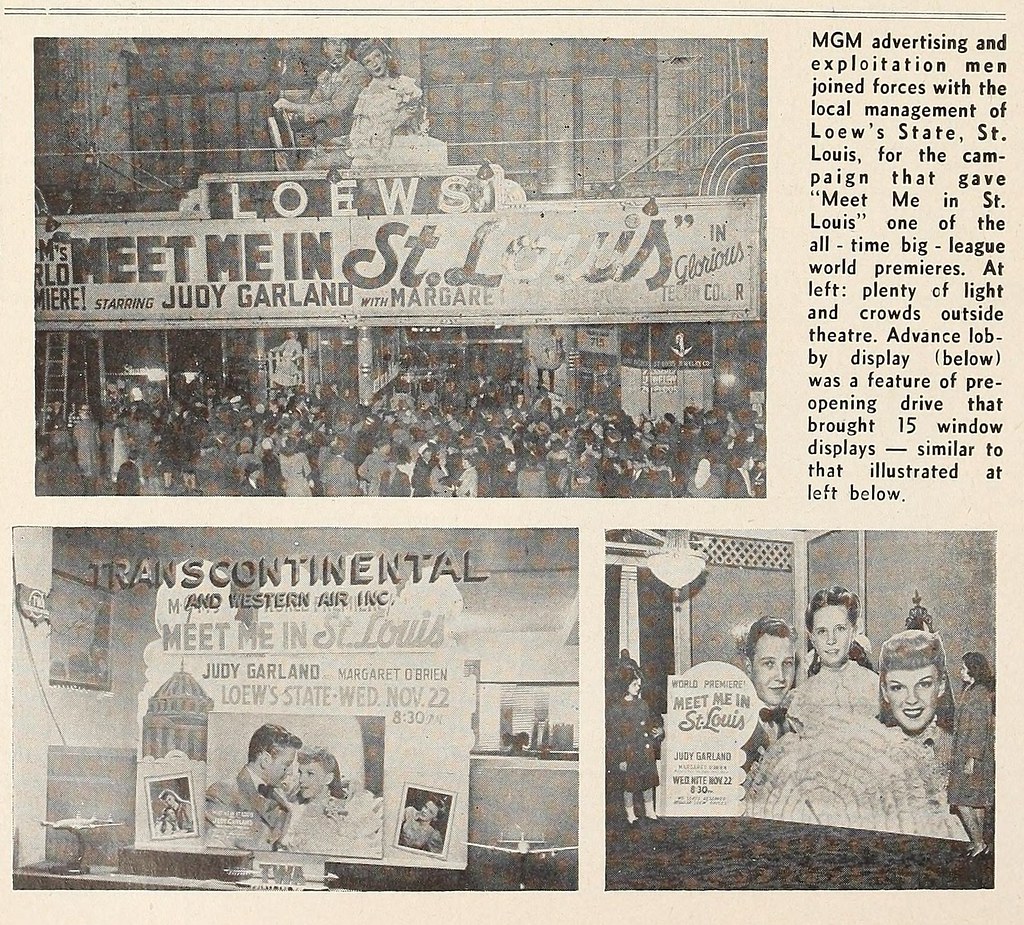

Meet Me in St. Louis had its world premiere at the Loew’s State Theatre in St. Louis on November 22, 1944. (The New York premiere followed a week later at the Astor Theatre in New York. It was at this time that Judy Garland announced her engagement to Minnelli.) The film proved to be a tremendous success for MGM. Despite its costly budget, the film managed to make over $6.5 million at the box office and was the second-highest grossing film of the year behind Going My Way. It was a critical success as well. Time magazine wrote, “Technicolor has seldom been more affectionately used than in its registrations of the sober mahoganies and tender muslins and benign gaslights of the period. Now and then, too, the film gets well beyond the charm of mere tableau for short flights in the empyrean of genuine domestic poetry. These triumphs are creditable mainly to the intensity and grace of Margaret O’Brien and to the ability of director Minnelli & Co. to get the best out of her.”

The film went on to be nominated for four Academy Awards (Best Writing/Adapted Screenplay, Best Cinematography/Color, Best Music/Scoring, and Best Music/Song for “The Trolley Song”). Though it did not win any of these, Margaret O’Brien was awarded the Juvenile Award for Outstanding Child Actress of 1944.

The film kicked off a string of major hits for Arthur Freed. With the “Freed Unit,” MGM released some of the greatest musicals that had ever been made– films like The Pirate (1948) and Easter Parade (1948) with Judy Garland, On the Town (1949), An American in Paris (1951), and Singin’ in the Rain (1952) with Gene Kelly, The Band Wagon (1953) starring Fred Astaire and directed by Vincente Minnelli, and many others. This was the heyday of the Hollywood musical, and Meet Me in St. Louis helped usher it in.

Meet Me in St. Louis is a brightly-colored portrait of Americana, evoking the imagery of Currier and Ives. But beneath the gorgeous look of the film is the heartfelt emotion that will resonate with families of today. Meet Me in St. Louis stands as a tribute to American families. Some of the more touching moments in this film are conveyed by Mary Astor, as the mother. In a quiet, understated performance, we see her attempt to pull the family together in the wake of Alonzo’s news. She goes to the piano to perform “You and I.” She is soon joined by Alonzo (but instead of Leon Ames’ voice, it’s Arthur Freed’s), and then the rest of the family returns and congregates in the parlor with mother and father at the piano. It’s one of the smaller moments that make the film so special. Meet Me in St. Louis has a sincere charm that is rarely equaled on film these days.

NOTE: Chicago Tribune film critic Michael Phillips will introduce the film at 7:30 PM and talk about Vincente Minnelli’s life in Chicago before his arrival in Hollywood.

~MCH