WHAT: Jaws (1975, DCP) Season Finale!

WHEN: June 14, 2023 1 PM & 7:30 PM

WHERE: Pickwick Theatre, Park Ridge, IL

WHAT ELSE: Organist Jay Warren performs pre-show music at 7:00 PM!

HOW MUCH: $12/$10 advance or $10 for the 1 PM matinee

Advance Tickets: Click Here!

Steven Spielberg’s Jaws is generally regarded as the first “summer blockbuster.” Although there were movie hits in prior decades, this is the film that set the standard for the modern era and how these types of genre pictures are distributed on a wide scale. Jaws quickly became a phenomenon when it was released in June of 1975, and it has remained one of the most popular and critically admired films of all time. As people get ready for summer vacation, we thought this was the perfect film to end our ninth season on. The Pickwick Theatre Classic Film Series will be presenting Jaws on Flag Day, June 14, 2023. This is scheduled to be the final classic film on the MEGA-screen before the series returns to its original screen in the fall.

There is a wealth of information available on the making of this film. Two recommendations are The Jaws Log (1975) by Carl Gottlieb and a two-hour documentary on the film, The Making of Jaws (1995), which is available on the blu-ray release. The former is essential, behind-the-scenes storytelling that shows in detail what a collaborative effort it was to create Jaws. The making of Jaws is almost as fascinating as the film itself, and we encourage fans to seek out these and other references. For the purposes of this article, we’ll relate some of the essential points…

Jaws was based on the best-selling thriller by Peter Benchley. The book, released in 1974, had staying power and would eventually be on the New York Times best-sellers list for 40 weeks. However, even before it was published, it had caught the interest of the movie industry. The screen rights were picked up by producers Richard Zanuck and David Brown of Universal. Benchley would go on to write three drafts of the screenplay before other writers became involved. One of whom was playwright Howard Sackler, but it would be Carl Gottlieb who would work on the final script as the film was being made.

Twenty-seven-year-old Steven Spielberg was not the initial choice to direct, but in the end he proved to be the best choice. Through the producers, he had read the novel and was immediately attracted to the story, which for him had parallels to his TV movie Duel (1971). This highly praised television thriller starring Dennis Weaver was set on land and involved a truck, but it mirrored the general structure of the shark story. At the time, Spielberg was more interested in the audience appeal and admittedly overlooked the technical challenges that would be involved in bringing the story to life. Zanuck and Brown had already produced Spielberg’s first theatrical film, The Sugarland Express (1974), and assigned the project to him. Bill Butler, who had shot Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974), would be Spielberg’s director of photography.

Although Spielberg himself had worked on the script in the wake of Benchley, one of his best creative decisions was bringing writer/actor Carl Gottlieb onto the project in April 1974. Together, they jettisoned the unnecessary subplots in the Benchley novel and gave it a linear simplicity. They significantly enhanced the story and turned the movie into a straight adventure with plenty of suspense. With the superfluous cut away, the synopsis of the story became straightforward…

A great white shark terrorizes the beach town of Amity near the start of the Fourth of July holiday. Police chief Martin Brody gets resistance from the town mayor, who wants to keep the beach open for financial reasons, but after the shark strikes again, Brody (with the town’s cooperation) enlists the help of a marine biologist, Hooper, and a professional shark hunter named Quint.

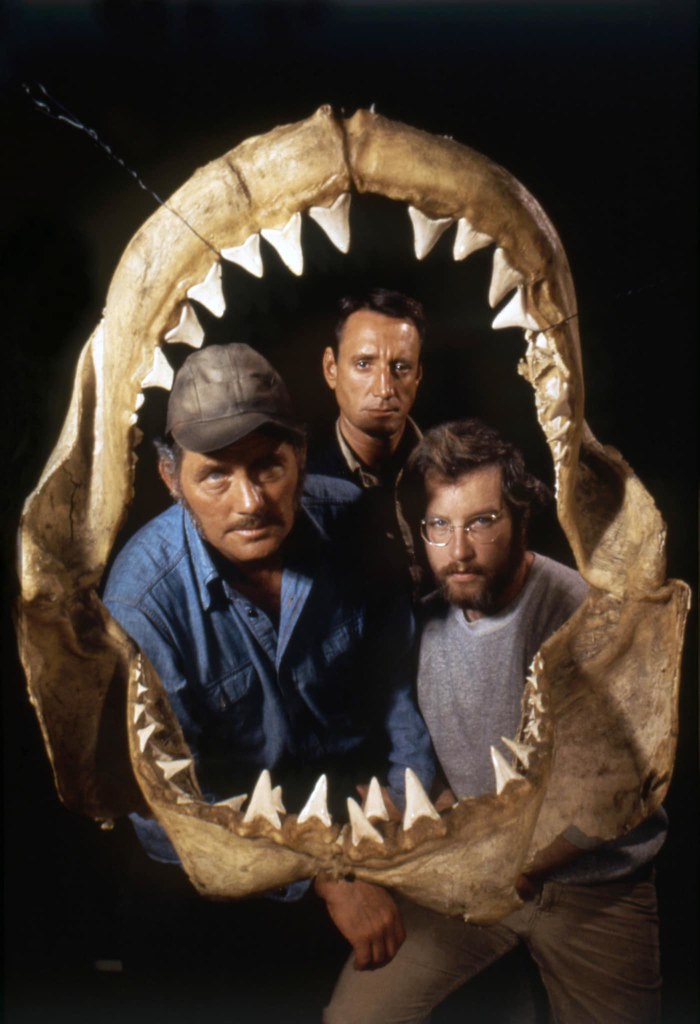

Murray Hamilton, who played the mayor of Amity, was the first actor cast. Roy Scheider, best known for playing a tough cop in The French Connection (1971), was cast as Brody. Richard Dreyfuss, who recently completed The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz (1974), played Hooper, and Sterling Hayden was set to play Quint. However, an inability for Hayden to work in the States at this time due to IRS issues forced the filmmakers to recast the pivotal role of Quint. Just days before the film was scheduled to begin shooting, the producers found that Robert Shaw was available and he agreed to play the role. Shaw had previously worked with Zanuck and Brown during the making of The Sting (1973).

Jaws was originally scheduled for 55 days of shooting and budgeted at $3.5 million, but it would go well over on both scores. (The final budget was over $9 million and the production took 159 days.) The filmmakers found the ideal location for filming in Martha’s Vineyard, an island off the coast of Massachusetts. In the film, it is known as “Amity Island.” The main reason this location was chosen over others around the world was because the sandy ocean bottom around the island was never deeper than 35 feet– even as far as 12 miles out to sea– thus allowing the filmmakers to operate the studio-built shark.

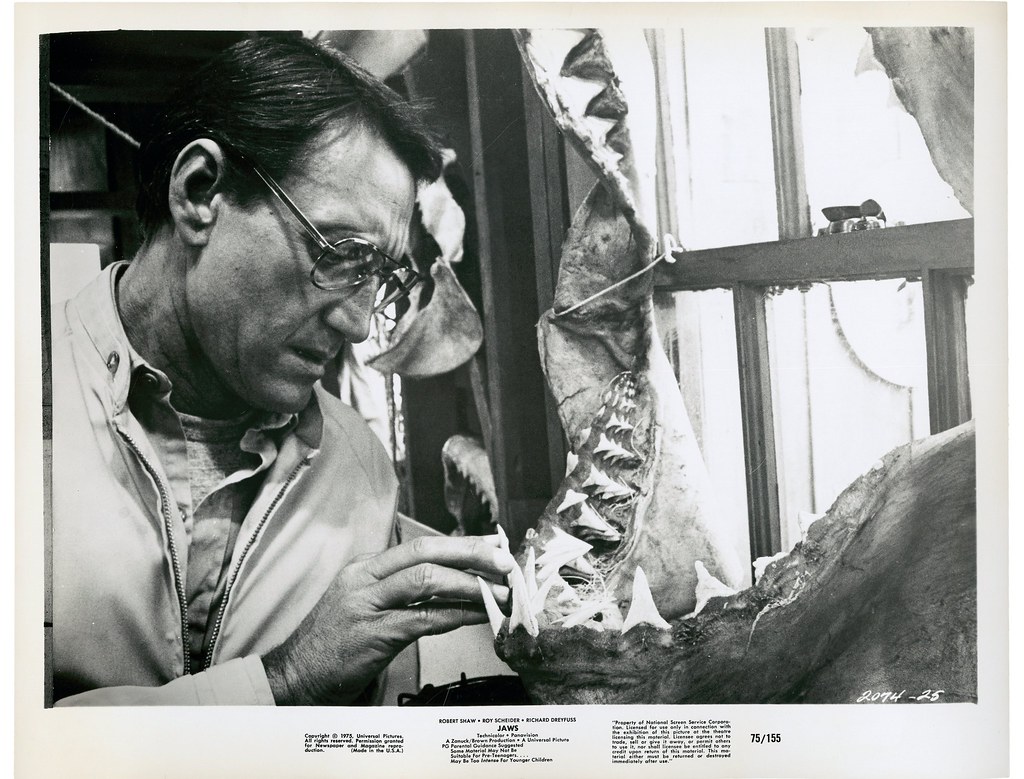

While the production began shooting on May 2, 1974, with the land scenes, legendary effects technician Bob Mattey and his team built and tested a mechanical shark that had been designed by production designer Joe Alves. Three of which were ultimately made to accommodate specific camera angles. The shark was generally referred to as “Bruce”– named after Steven Spielberg’s lawyer. In The Jaws Log, Gottlieb explains the design of the 2,000 pound shark as well as the 14-ton shark mechanism involved with operating it:

“There were, all told, three full-scale models of the twenty-five-foot great white. Each one was made of welded tubular steel, with flexible joints hinging moving sections. The tail swung from side to side, the sides rolled, the fins waved: the models moved like real sharks. One was entirely open on the left side, one was open on the right side, and one was solid and complete. The open ones would always present their complete side to the camera, and would be attached to the steel platform sunk on the bottom of the ocean, riding the trolley along specially greased rails, simulating swimming action. They could dive, surface, look to camera, bite, snarl, chew, flop their tails, and carry on most realistically for sixty or seventy feet of travel. The closed shark was attached to a “sea sled,” a complicated submerged mechanism consisting of rudder planes and bracing, like a skeletal submarine. This baby could maneuver freely along the surface, guided by scuba divers with oxygen tanks riding the sled around below the waves, working the fins and planes.”

When Bruce was shipped East from California, the filmmakers discovered he didn’t respond as favorably in ocean water. Another matter was the paint, which simply didn’t look real enough on the “skin.” (Carl Gottlieb describes the flesh as being made of neoprene foam with nonabsorbent, closed cells, over which was a polyurethane skin with a nylon stretch material for the joints.) As each issue came up, the crew was able to find a workable solution, but this cost time and sent the film days and eventually weeks over budget.

Jaws was unique in that it was shot on the open ocean– not on a studio lake. This was unheard of in 1974 for an effects-driven film like this. The last 47 pages of the script, which were set on the sea, would be the most difficult. Some of the longest delays came during the film’s second act which involves the three main protagonists confronting the great white. In addition to the Orca boat, which was used for scenes on the ocean, a mock-up was also designed for those in which the boat sinks.

Due to various setbacks and technical challenges brought on by the shark’s inability to cooperate, Spielberg was forced to shoot around the shark. He suggested the shark’s presence, such as showing the moving buoys, instead of actually showing the shark itself. Camera angels were planned around the position of the shark in the water, and Spielberg had to think like an engineer. The technical limitations actually forced him to be more creative as a director. As a result, he made not only a better film, but one of the best in his entire career.

The screenwriters took great pains to make the characters believable. Roy Scheider is perfectly cast as the “every man” sheriff who hates the water, and of course, Robert Shaw had a remarkable reputation as an actor. Shaw also contributed to one of the most dramatic moments in the screenplay in which his character tells of his near-fatal experience on the USS Indianapolis during World War II.

According to screenwriter Carl Gottlieb, it was Robert Shaw who should be credited with the writing of the dialogue. (The uncredited Howard Sackler, according to Spielberg, conceived the idea of the speech.) Shaw was himself a novelist and playwright and was able to assimilate what earlier writers had attempted to do. But it’s his performance of this monologue that is so riveting, and it reveals why he was Fate’s choice to play Quint.

The character of Quint clearly had a literary prototype in Ahab from Herman Melville’s Moby Dick (1851). But the color and dialogue of the characterization was also heavily influenced by a Martha’s Vineyard local by the name of Craig Kingsbury (Kingsbury played the character of Ben Gardner in the film.) It’s these types of strong characterizations in this epic tale of man versus nature that makes Jaws the cinematic equivalent of great literature.

Of course, Jaws would not be remembered quite as well without the John Williams’ film score, particularly the two low notes heard in the main title. This simple arrangement has now become synonymous with the approach of danger (or a fin breaking the surface of water). Williams created an association between sound and image and formed a collective memory for audiences that is still with us today. Think of Bernard Herrmann’s underscoring for the shower scene in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). As a result of this film in general– and this music specifically– the shark species has become demonized on film as man-hunting, evil forces of nature. John Williams would go on to win an Academy Award for his score.

Another Oscar winner on this production is editor Verna Fields, who had assembled George Lucas’s American Graffiti (1973). She had the task of condensing 400,000 feet of film down to 11,000 feet. Unlike many editors who only appear in the studio editing rooms, Verna was actually on location with the filmmakers. One of the final scenes shot for the film– the shocking appearance of fisherman Ben Gardner’s floating head– was shot in her own L.A. swimming pool!

With its box office receipts of $123 million (on its initial release) and a marketing campaign that saw every imaginable form of movie merchandise, Jaws became something more than just a hit; it became part of our culture. In the mid-1970s, it ushered in the type of films audiences wanted to see. Of course, that has since evolved into summer movies that aren’t very good; but in 1975, it was a call-back to the days of epic film-making with grand stories and heroic characters moviegoers could root for. Spielberg was different from his contemporaries in that he was apolitical; his movies didn’t have the political agendas seen in other films of the 1970s. As a result, his brand of cinema was a refreshing escape from the oppressive cynicism of that decade.

Unlike today’s company-packaged CG-fests designed for 10-year-olds, Jaws is a legitimately great summer movie because of its characterization, humanity, and detailed, handmade construction. Its worldwide success would eventually spawn three sequels of gradually lessening quality (and by the fourth entry, poor receipts). But nearly fifty years later, the original still engages us. It still frightens us out of our seats. And Jaws is a movie that still makes us afraid to go into the water.

~MCH