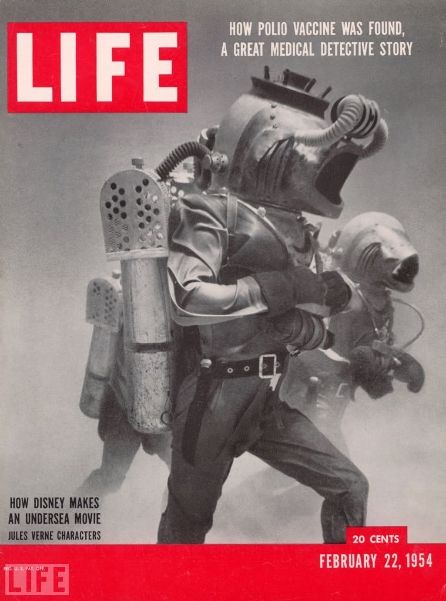

I thought for this entry I would quote at length from film director Richard Fleischer’s wonderful memoir, Just Tell Me When to Cry (1993). In Chapter VIII, Fleischer offers insightful revelations on working with Walt Disney, hunting and killing sharks, and handling a difficult star like Kirk Douglas. The following excerpt underscores the hazards of working underwater…

“We were into the last few weeks of shooting, in Nassau, when Life magazine sent Mary Leatherbee, their entertainment editor, and a still photographer to cover our moviemaking. They got all the material they needed for a good story, but Leatherbee still wasn’t satisfied. What they needed, she felt, was an exciting episode, like an underwater emergency. As far as we were concerned, that was the last thing we were looking for. (Water expert Fred) Zendar was a fanatic about water safety and so far we hadn’t had a single situation where a diver had to be taken out of the water in a hurry.

On their last day with us, since nothing untoward had happened during their stay, we agreed to stage an emergency for them. Almost as soon as we got in the water for our first shot of the day, we had an emergency, the real thing. One of the actor/divers tore his suit on a piece of coral. Zendar and the safetymen went into action, and they had that diver out of the water, with his helmet off and breathing fresh air, in less than two minutes.

We had no sooner dealt with that situation when a second emergency occurred. Life magazine was running in luck. But this was an odd accident. Nobody, not even Zendar, could have anticipated it.

There were two kinds of divers on the picture: safetymen, and those we were photographing, called actor/divers. The safetymen wore Aqua-Lungs and could swim freely and unencumbered. The actor/divers were a different matter. They had to wear what appeared to be a version of the traditional deep-sea divers’ outfit, with lead-weighted, heavy boots and a brass helmet. The difference between these outfits and the conventional ones was that we couldn’t have an air hose leading from the helmet to the surface. Our divers had to be self-supporting and completely independent.

No diving gear like this had ever been built, so Harper Goff and Fred Zendar designed and engineered a new model. The basis was the Aqua-Lung, with the mouthpiece inside the brass helmet. There were two problems, however, that had to be solved. One was the mouthpiece. Since it was to be inside the helmet, what would happen if it accidentally dropped out of the diver’s mouth? He couldn’t use his hands to pop it back in again. The solution was to support the mouthpiece on a rigid tube so it would always be in the same position. In that way a diver could deliberately let go of the mouthpiece and then regain it simply by leaning his head forward.

The other problem had to do with exhaled air. The diver would be getting oxygen through the Aqua-Lung, but his exhalations went directly into the suit. It wouldn’t take long before the suit had so much carbon dioxide it would blow up like a balloon. That could result in a calamity, because the carbon dioxide-filled suit could rocket up to the surface, where the lack of water pressure would cause it to burst. That in itself wouldn’t hurt the diver, but because of the heavy boots and the brass helmet, the diver would sink to the bottom like a stone. It is an event known among deep-sea divers as a fusca.

There was a simple solution to that problem, too. Goff and Zendar had a valve installed in the back of the helmet that would vent the exhaled air. Whenever a diver felt himself getting too buoyant, all he had to do was hit the back of his head against a plunger. The plunger opened the valve and– voila— the air escaped.

One of the divers, Shorty, had been having a minor problem with the plunger. It was a little stiff, and the back of his head was getting bruised from hitting it against it. He was too macho to mention it to anyone, so he found his own solution. He would wear a woolen sailor’s cap, and that would cushion the impact. This particular day was the first time he’d tried it.

It seemed to work fine. Then he began to notice something disquieting. Each time Shorty hit the plunger with his head it pushed the cap a little farther down on his forehead. There was no way to fix this. He couldn’t get his hands inside the helmet. It wasn’t long before the cap, slowly but surely, slipped down over his eyes. Now he was completely blind.

Shorty did the only thing he could do: raise one arm with a clenched fist. This was one of our well-rehearsed underwater signals that meant, ‘I’ve got a problem. Not serious.’ The actor-diver closest to him tried to look through his face plate, but it was too dark and he couldn’t see anything. The divers had learned early on that if you put your helmet against someone else’s helmet, and let go of the mouthpiece, you could carry on a perfectly clear conversation. He did this and said, ‘What’s the matter, Shorty?’

Shorty let go of his mouthpiece to answer. ‘My cap,’ he said, ‘is covering…’ As he spoke, the cap slipped farther down and covered his mouth. Now he was not only blind but also he couldn’t get the mouthpiece back into his mouth to breathe. Once again, he did the only thing he could do. He raised both arms with clenched fists. This meant, ‘Get me out! Quick!’ The safetymen went back into action, and Shorty was breathing fresh air in just about one minute.

The Life story turned out great. We got the cover and an eight-page picture spread. The only sour note in it for me was that throughout the piece the credit for directing the movie was given to someone called Robert Fleischer. The name of one of the divers who had an emergency was Eddie Czynski. They got that right.”

* * * * * *

For more photos from the Life magazine shoot, be sure to visit Tom Scherman’s blog by clicking here!