WHAT: High Noon (1952, DCP) Season 10 Opening Night

WHEN: September 13, 2023 1 PM & 7:30 PM

WHERE: Pickwick Theatre, Park Ridge, IL

WHAT ELSE: Organist Jay Warren performs pre-show music at 7 PM; The Three Stooges short, “Shot in the Frontier” (1954).

HOW MUCH: $12/$10 advance/$10 for the 1 PM matinee

Advance Tickets: Click Here!

“Above all, it is a film about ethics and morality, and their intersection with the social world of citizens and law and order– themes which, endearing High Noon to successive generations of the world audience, including US Presidents from Eisenhower to Clinton, draw the film out of the fifties and project a longer and more complex vision of the cultural and ideological role of popular cinema.” ~Phillip Drummond, High Noon (BFI Film Classics)

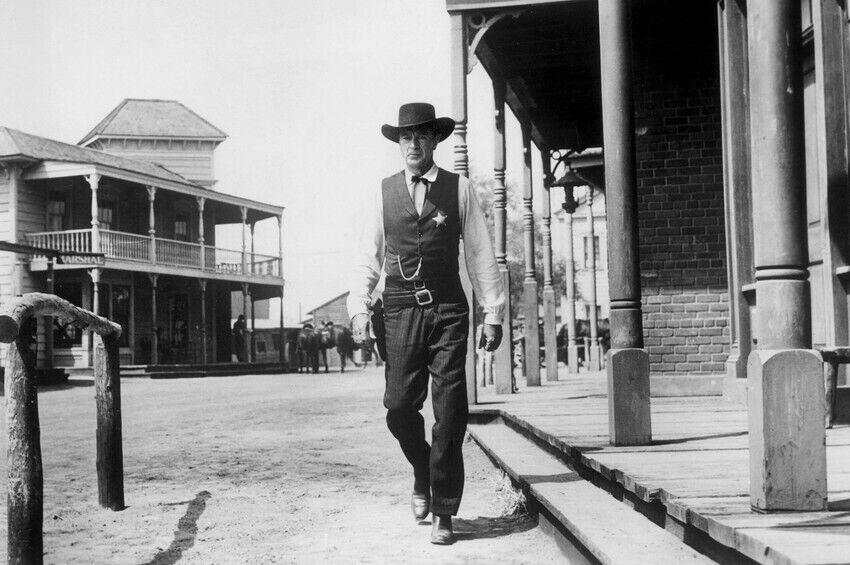

This September marks the tenth anniversary of the Pickwick Theatre Classic Film Series. Over the course of ten seasons, we’ve screened several super-Westerns such as The Searchers, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Once Upon a Time in the West, The Magnificent Seven, and Rio Bravo. For our official Opening Night, we thought we’d return to the genre with one of the most revered and, in some quarters, controversial Westerns ever made, 1952’s High Noon. Produced by Stanley Kramer and directed by Fred Zinnemann, the film features Gary Cooper as a marshal who must defend his town against a band of outlaws seeking revenge. The film won Cooper his second Academy Award for Best Actor. Since its release, High Noon has gone on to be recognized as one of the finest films ever made, placing 33rd in the AFI’s ranking of the greatest American films.

The nature of the controversy stems from the creative force behind High Noon and the subtext of the film. High Noon‘s screenplay was written by Chicago-born Carl Foreman, who was blacklisted by the movie industry during the height of the “Red Menace” in America. Shortly after production began, Foreman, who also served as the associate producer for Stanley Kramer, was called to Washington to testify at the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Foreman was deemed an unfriendly witness due to his refusal to name names.

As a result of this congressional hearing, Foreman’s career in Hollywood came to an abrupt end. Actor John Wayne, then president of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals, famously took pride in “running Foreman out of town” despite the fact that Foreman had actually left the Communist Party in the 1930s and, unlike Wayne, had served his country during World War II (with the US Army Signal Corps).

As a result, the script of High Noon was viewed in the context of Cold War politics. The lone marshal abandoned by his community came to represent the screenwriter himself. Former friends of Foreman closed their doors on him and distanced themselves for fear of guilt by association. Kramer bought Foreman out of their company and essentially turned his back on him. Foreman would go into exile in England.

Wayne came to view the film as un-American for other reasons. The shot in which Cooper tosses his badge onto the ground infuriated Wayne as well as director Howard Hawks. Their response to High Noon was Rio Bravo (1959), which depicted its hero as a professional who didn’t need to go around town asking for help. Despite the animosity Wayne had towards the film, he seemed to whistle a different tune at the Academy Awards when he accepted Gary Cooper’s Best Actor Oscar on his behalf. He expressed regret at turning down the role of Marshal Will Kane.

Carl Foreman’s screenplay freely borrowed elements from a 1947 John Cunningham short story called “The Tin Star,” as well as from Owen Wister’s seminal 1902 novel, The Virginian, which also featured a lawman having a showdown on his wedding day. High Noon was one of a handful of films Foreman wrote for Stanley Kramer between 1948 and 1951. Kramer wanted the film done fast. He had just signed a new deal with Columbia but had to fulfill his contractual obligations to distributor United Artists. The film’s budget was set at the relatively low $730,000, and it would be shot in just 28 days between September 5 and October 14, 1951.

Shortly after his marriage to Amy, Marshal Will Kane learns that a former nemesis, Frank Miller, has been released from prison and is on his way back to Hadleyville to seek revenge. Miller’s gang is waiting for him at the train station. The townsfolk initially convince Kane to leave town with his new bride, but Kane realizes that he has a moral obligation to fulfill. He turns back in the direction of town and seeks out a posse for the confrontation. However, one by one, for one reason or another, those who can help turn him down. Even Kane’s wife turns her back on him and his decision to stay. While waiting for her homeward-bound train at the hotel, Amy confronts Helen Ramirez, an old flame of both Frank Miller and her husband. Ramirez, a successful businesswoman, doesn’t understand how Amy could leave her husband in his hour of need, but gun violence in Amy’s family has led her to her Quaker beliefs. Despite departing Hadleyville with Ramirez, the sound of distant gunshots brings Amy back. She returns in time for the final showdown between Will and the outlaws.

In addition to Gary Cooper and the relatively unknown Grace Kelly, the main cast included Mexican actress Katy Jurado as Helen Ramirez, Lloyd Bridges as Deputy Marshal Harvey Pell, and Thomas Mitchell as Mayor Jonas Henderson. Otto Kruger was cast as the judge who hightails it out of town. Lon Chaney, Jr. portrayed the arthritic former marshal, and character actor Ian MacDonald played Frank Miller. In his first role (without any spoken dialogue) is Lee Van Cleef as one of the outlaws.

Gary Cooper, then 50 years old, was the quintessential American on-screen and was perfectly cast as the dutiful lawman. He had made a career out of playing average Joes, soldiers and heroes of the American West. The latter conjured up certain romantic notions of the frontier that fit the Cooper image. Throughout the film, Cooper suffered from ulcers and a bad back. These physical ailments helped contribute to the aggrieved state of the character. Will Kane never enunciated his inner turmoil. Instead, the psychological element was conveyed through song, specifically, the High Noon ballad (“Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darling”) as sung by Tex Ritter.

High Noon was shot by Viennese director Fred Zinnemann, who had once worked with the legendary independent filmmaker Robert Flaherty. More recently, Zinneman had made Act of Violence (1948) for MGM, and he would go on to direct From Here to Eternity (1953). His cinematographer, Floyd Crosby (the father of musician David Crosby), had also been a collaborator with Robert Flaherty, among other great pioneers. Crosby had won an Academy Award for Best Cinematography for F.W. Murnau’s Tabu (1931). He would later shoot several of the Roger Corman horror films in the 1960s for American International Pictures. For High Noon, the film would be photographed in stark black and white, which was a contrast to the color of most Westerns of the day. Refusing to use filters, Crosby went for a naturalistic look that suggested the pictures of Civil War photographer Matthew Brady.

High Noon was shot on the “Western Street” on the Columbia ranch in Burbank, as well as in Sonora, California. During the course of the shoot, Zinnemann made extensive use of story-boarding, which contributed to the film’s precise construction. The film’s tense structure was built around the threat (the gunmen waiting for the train to arrive), the marshal going around town looking for assistance, and the recurring image of the clock. The story unfolds roughly in the time it takes to watch it. In this sense, it follows the approach of films like Robert Wise’s boxing noir, The Set-Up (1949). However, the Zinnemann film does in fact manipulate time under close scrutiny. The film’s great success in how it suggests the passage of time is through the editing by Elmo Williams and Harry W. Gerstad. Both would win Oscars for Best Film Editing.

In addition to Cooper’s Oscar and the Best Editing win, High Noon would win Academy Awards for its music. “The Ballad of High Noon” won for Best Song and composer Dimitri Tiomkin was recognized for Best Scoring. The film was unique in its day in that it does not open with a traditional orchestral score, but rather with the recurring theme song. As previously noted, the music adds an extra psychological level, suggesting things that are not spoken by the hero. Besides its wins, the film was nominated for Best Motion Picture, Best Director, and Best Screenplay.

Its blacklist-era politics aside, the film can also be read as a treatise on American foreign policy, specially, our relationship with the United Nations. Often America has taken the lead when other countries have been too timid to act in the face of crisis. But examining the story itself on its face value, High Noon is far from being “un-American,” as Wayne had suggested. Marshal Will Kane had literally hung up his badge after his marriage and had every right to leave town with his wife at the start of the picture. But he made the moral choice to stay and fight. Since he was outnumbered, trying to round up a posse was probably smarter than the macho heroics of going it alone. And ultimately, he is alone until the very end. His rejection by the townsfolk and their cowardice to do anything is strongly conveyed throughout the film. It could be argued that this scenario is probably more true to real life and how people would react!

High Noon is a film that went against convention: a tight black and white, low-budget movie with a Western hero who winds up standing outside his community. Unlike other Western heroes, he conveys to the audience, though never verbally expressed, a fear and the expectation of death. Despite this, he is a character driven by his conscience to stay and fight– and to do what is right. He refuses to desert the townsfolk despite their attitudes and self-interests. In the end, after he has finished the job, he shuns the town that had shunned him.

Producer Stanley Kramer and director Fred Zinnemann never saw High Noon as a political picture, but it can certainly be interpreted as such due to Carl Foreman’s involvement. That perspective aside, the film’s basic premise remains just as relevant today. High Noon shows us the unrewarding bleakness of the lawman’s job– the self-doubt, the frustration– but there is also the moral courage that propels one forward. It’s all there on the big screen in one of the best Westerns we’ve ever presented at the Pickwick Theatre Classic Film Series.

~MCH