The following is a transcript of my presentation on The Ladykillers at the Park Ridge Public Library on April 12, 2018. This was our final show of our 10th season. We had 75 patrons in attendance. ~MCH

For the past six weeks we’ve revisited the classic comedy of Ealing Studios. Our first film in the series was 1949’s Whisky Galore!, although most historians cite 1947’s Hue and Cry as the first important film in this cycle. It should be pointed out that Ealing made earlier comedies with talents like George Formby and Will Hay. The latter’s 1943 film, My Learned Friend, was a black comedy that influenced some of the Ealing films to come. However, when fans talk about the best of Ealing comedy, the years 1947 to 1955 are generally considered the peak period. During this time, the studio produced a series of films of superb quality, critical acclaim, and popular appeal. The least of these are simply enjoyable while the best are masterpieces. This golden age effectively came to a close with one last work of brilliance: 1955’s The Ladykillers, a crime caper directed by Alexander Mackendrick and starring Alec Guinness.

In The Ladykillers, Alec Guinness plays Professor Marcus, an eccentric but well-mannered criminal mastermind. Posing as a member of a “string quintet,” Marcus rents out rooms from Mrs. Wilberforce, a sweet old lady who lives in a lopsided, Victorian home in a cul-de-sac. With his four associates, Marcus intends to use the woman as an unknowing accomplice in their well-planned heist. But are five men enough to contend with Mrs. Wilberforce?

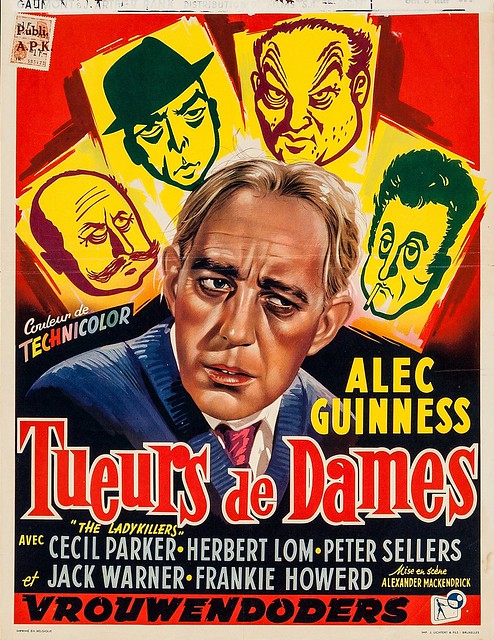

Belgian poster for The Ladykillers

Film critic Philip French says of these characters, “The gang of four led by Guinness are the punch-drunk ex-boxer One-Round (Danny Green); the ruthless, unsmiling mittel-European heavy Louis (Herbert Lom); a puffy London teddy boy, Harry (Peter Sellers, given his first extended film role by Mackendrick, a fan of BBC radio’s The Goon Show, of which Sellers was a star); and the bluff phoney Major Courtney (Cecil Parker), a cowardly poseur with a dubious military record we can only guess at. They are a cross-section of social types, unromantic failures living shadowy lives of self-deception, thieves without honour constantly bickering among themselves.”

The screenplay was by William Rose, an American ex-patriot who had written an earlier comedy for Alexander Mackendrick called The Maggie. He later returned to America where he wrote the scripts for It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. Rose said of The Ladykillers that the story idea came to him in a dream, and the film does have a dream-like quality. Characters are entrapped, not just by the claustrophobic character of the house but by the will of a harmless old lady who simply wants to do the right thing.

(clockwise from rear) Herbert Lom, Peter Sellers, Cecil Parker, Danny Green, Katie Johnson,

and Alec Guinness

The film blends the realism of earlier Ealing films, such as its use of location shooting, with a high stylization. Particularly effective is the scene in which Marcus follows Mrs. W home and is seen only in silhouette. The staging of the scene, which establishes a real sense of menace, recalls German Expressionism and the work of director Fritz Lang. The exaggeration—in performance as well as in Guinness’s almost grotesque character makeup– adds to the dream quality and the film’s macabre sense of humor.

Alexander Mackendrick, as we’ve seen before with Whisky Galore! and The Man in the White Suit, was one of Ealing’s most important and original directors. With filmmaking colleagues like Robert Hamer and Charles Crichton, Mackendrick defined the Ealing style and took the studio in new directions. On the surface, these films followed a pattern that had been established by studio head Michael Balcon– an emphasis on ordinary British citizens, for instance– but at the same time, they offered something more at a subversive level. Beneath the whimsical humor there was also social satire. It has been argued that Mrs. Wilberforce’s connection to the past symbolized Britain’s own unwillingness to move forward with the times. The Ladykillers certainly has deeper layers that can be interpreted several ways. This was Mackendrick’s last film in England before leaving for America. But he left behind one of the darkest comedies Ealing ever made. Mackendrick’s next credit would be an even darker film– 1957’s Sweet Smell of Success.

Seventy-six-year-old Katie Johnson portrayed the innocent Mrs. Louisa Wilberforce. A symbol of the British Empire, Wilberforce is a throwback to the dusty grandeur of the Victorian era and its traditional values and morality. She instills a genuine sweetness into the film that nicely counterbalances the criminal element. Katie Johnson’s acting career had started on the British stage in the mid-1890s, and it wasn’t until the early 1930s that she made her first film. But The Ladykillers would be the first time she received any recognition for her acting; she earned a British Film Academy award for best actress as a result. Philip French writes, “In fact, the film’s dramatic drive derives both moral and comic force from the way Katie Johnson’s superb performance embodies both a theme that Mackendrick pursued through most of his films, and the allegory about Britain at mid-century that he and the screenwriter William Rose built into their film.” The Ladykillers would be Katie Johnson’s second-to-last film. She passed away in 1957.

For the role of Professor Marcus, it’s been said that Guinness modeled him on actor Alastair Sim, who was Mackendrick’s first choice for the part. Alec Guinness was Ealing’s biggest star and was internationally known, so Balcon insisted he be cast. Professor Marcus would be another memorable performance for Guinness. Author Robert Sellers writes of the character’s creation, “Guinness’s first approach was to play him as a cripple, dragging his leg pathetically across the floor. ‘In my office Alec gave an imitation of a cripple which was really gruesome,’ Mackendrick recalled. ‘Horrendously funny, but stomach-turning in its effect. So I had to say, no, sorry, Sir Michael Balcon will never, never stand for that.’ Guinness was a bit put out by this and went over to the window as Mackendrick continued going through the script. As he talked, Guinness grabbed a pair of scissors and cut out some paper teeth, which he nonchalantly popped in his mouth, turned round and grinned at Mackendrick. The effect was startling.”

Two years after The Ladykillers, Guinness would win an Oscar for his performance as Lieutenant Colonel Nicholson in The Bridge on the River Kwai—one of several collaborations he made with director David Lean. Guinness’ later career has been well-documented, but in regards to his association with producer Michael Balcon, he appeared in one more film under the Ealing banner. Barnacle Bill (aka All At Sea) from 1957 is considered to be the last Ealing comedy even though it was shot at another studio. Guinness did the film only as a favor to its director, Charles Frend, but considered the film, perhaps unfairly, to be “wretched.”

Michael Balcon sold the Ealing studio to the BBC in 1955 but continued producing films elsewhere under the Ealing name. But all good things must come to an end. Balcon eventually sold his assets and Ealing, a quaint studio which had projected the English character for a quarter of a century, gave way to the era of the British New Wave. To those who had worked at the “little studio with the team spirit,” fond memories remained. These memories have been well-documented in Robert Sellers’ The Secret Life of Ealing Studios. Though the writers, directors, and actors are all mostly gone now, the films remain. Over sixty years after Ealing made their last great comedy, film buffs today are still talking about them. For a brief time– just under nine years– Ealing set the gold standard in comedy. Though they made wonderful films of all genres, their most famous productions are movies like Kind Hearts and Coronets, The Lavender Hill Mob and The Ladykillers. It’s a wonderful legacy to have and one that will certainly last.