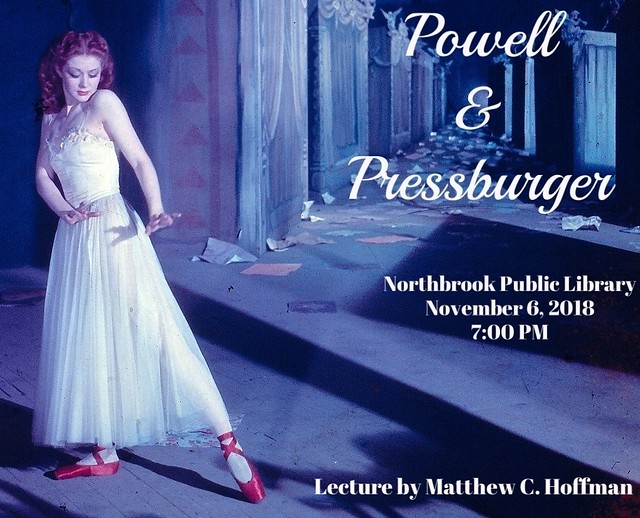

The following is a transcript of my presentation on “Powell & Pressburger” that was given at the Northbrook Public Library on November 6, 2018. Thank you to the staff of the Northbrook Public Library and to those who came out on Election Night to support the program. Almost a third of the audience left with some prizes we gave away!

Introduction: Why Powell?

For those not already familiar with the name of Michael Powell, he made some of the greatest films in British cinema; they were unconventional and challenged the usual ideas of what British cinema could be. At the same time, his films mirrored England. He had a string of artistic and commercial successes, particularly in the 1940s. Powell and his longtime writing partner, Emeric Pressburger, formed a unique partnership for the better part of twenty years. Powell always insisted it was a fifty-fifty partnership, and the screen credits reflect that: “Written, Produced and Directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger.” Together, they were known as The Archers, which was the name of their production company. Their trademark, seen at the beginning of every movie, depicted an arrow being shot into a bull’s eye. Their films are recognized as classics of world cinema and have inspired countless filmmakers, particularly Martin Scorsese, whose editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, was married to Michael Powell until his death in 1990.

I was a film student at Columbia College Chicago in the mid-1990s, and during this time I remember one of my film instructors, Scott Marks, giving me VHS copies of movies like Peeping Tom and 49th Parallel to watch. The latter especially made an impression on me. It was one of the wartime films Powell had made that told the story of a German U-Boat crew that gets stranded in Hudson Bay, Canada, and is forced to make their way across the provinces to a neutral country. It was designed as propaganda with the intent of scaring America into the war. What struck me was the location photography. The film was actually shot in Canada. The film also benefits from several key performances by actors seen regularly in the Powell and Pressburger canon– actors like Eric Portman and Anton Walbrook. They were not big “stars,” but The Archers saw beyond conventional casting.

The other VHS tape I was given was Peeping Tom, which was a later film that Powell had made on his own about a disturbed young man who kills women with a movie camera tripod. Released a couple months before Hitchcock’s Psycho, Peeping Tom was a controversial film at the time and the British critics eviscerated Powell because of it. It did not officially end his filmmaking career because he made films after that like Age of Consent, but he was no longer a “bankable” director. Peeping Tom came towards the end of a career that went back to the 1920s.

Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger

After being introduced to Powell and Pressburger through Scott, I was excited to learn he would be teaching a class on their work. I registered immediately because Scott was the most knowledgeable film teacher I ever had, but he left Columbia shortly before the class was to begin. As a last-minute replacement, the college got a Chicago film critic to teach it. The critic knew almost nothing about Powell, and it’s safe to assume he had not read Powell’s A Life in Movies. He was learning as he went along, just as we were.

One thing that immediately grabbed my attention through the films we saw in that class– and through the clips of other films shown– was the gorgeous, three-strip Technicolor. There are few filmmakers who took better advantage of Technicolor than Powell and Pressburger. Films like Black Narcissus and The Red Shoes are two of the finest examples where color becomes a part of the story. The Red Shoes will be screened at Northbrook on November 28.

One lecture isn’t enough time to discuss the entire spectrum of their careers. To give you an idea of what an epic life Michael Powell had, his A Life in Movies is over 700 pages of small print (in the case of the paperback). And this is just the first volume! He followed this up with Volume 2, Million Dollar Movie, which chronicles the second half of his career after The Red Shoes. It is one of the finest autobiographies written and well worth your time. This is not just a history of Powell’s life, but a history of cinema itself.

I’d like to fade in at the very beginning and explain where these two remarkable filmmakers came from…

Man of Kent

Michael Powell was born in 1905 near Canterbury, Kent, in southeast England. He grew up, with his older brother John, on a farm. His family grew hops, but his father, Thomas William Powell, had a restless spirit and could not be tied down to farm life for long. Michael had a deep affection for his mother, Mabel, who cultivated his interest in reading. He was always proud of the fact that he was a “Man of Kent,” and this love for country manifested itself years later, particularly in his film A Canterbury Tale, which is evocative of time and place and contains memories from his childhood.

Michael attended King’s School in Canterbury and later, Dulwich College. He favored reading to sports and despised cricket and games in general. He knew many of the classic adventure stories by heart and spent hours in the library or in the local bookshop. During this formative period in his life, his mother had been deserted by his father. The elder Powell was more an adventurer who liked to gamble; he went into the hotel business and developed connections that would later prove beneficial to his son.

Around this time, Michael discovered an article in a 1920 issue of Picturegoer magazine that caught his attention. In reading it, he was fascinated by the camaraderie of a film company. He became a film buff and knew he wanted to be a director. The influence of films of movie pioneer D. W. Griffith were a major factor in his decision. Well versed in movies of the period—what he called the joy of his youth– this dreamy schoolboy was more interested in sneaking into movie theatres. Yet, he kept this moviemaking dream close to his vest when, in October of 1921, he made a foray into the banking world. He knew he was unsuited for a life as a bank clerk.

Thomas Powell had gotten the lease at a hotel on the Riviera. The winter season was always the busiest time. While balancing his mistresses, he operated two hotels, one in the north of France and the other in the south. Michael worked here for his father doing various chores, such as minding the wine cellar. At this time in France, Americans were shooting films practically in their backyard. The MGM studio was making a film in Nice. With his father’s help and the proper introductions, Michael was able to get a job at the Victorine Studios.

The year was 1925. The silent film director Rex Ingram was shooting a film at the time called Mare Nostrum with his wife, Alice Terry, as the star. While at the studio, “Micky,” as he was known, worked as the official stills photographer for the publicity department. At one point early in his career, he had to hide out in the studio after being fired from the stills department. Suffice to say, he managed to stick around once tempers cooled. He had access to all the departments and was able to learn from the cameramen and the film editors– or cutters, as they were known then. While working for Rex, he observed that the director had capable craftsmen– but not the artists that were needed. Michael knew that other filmmakers like Douglas Fairbanks had the courage to seek out great artists. Michael Powell knew that when the day came when he made his own films, he would get the best talent he could find.

His next film was Ingram’s The Magician, which was the first film he worked on from start to finish. He even managed to make an appearance in front of the screen:

“The sequence at the fair marks my debut as one of Rex’s clowns. My angelic seriousness must have amused him, for he suddenly announced on the night of the shooting that I was to be included as comedy relief… I was clapped into a make-up chair, covered in Leichner make-up, had my head shaved, was allotted a battered suit of clothes, a pair of glassless spectacles, a toy balloon, and a bag of bananas—I have said that Rex’s comic sense was rudimentary—and was told to be funny. I tried.”

Powell had fond memories of working at the Victorine Studios. He spent three years in the south of France for MGM, a member of an ex-patriot unit under a great director in Rex Ingram. These were the early days of filmmaking when everything had to be invented. He performed many tasks including writing the final titles for the movie. Powell’s first screen credit came when he played a tourist. Later, again in front of the camera, he appeared in a series of short subjects called “Travelaughs” in 1927.

Through a contact at MGM, Powell went to London in 1928 and worked for British International Pictures. When he first came to England, he got the job of stills photographer at Elstree Studios. Powell was the photographer during the period when Alfred Hitchcock was making Champagne. He developed a friendship with Hitchcock and took the stills on all of Hitch’s pictures at this time. More importantly, Powell worked on the script of Blackmail, Hitchcock’s first “talkie,” and helped devise the film’s climactic chase inside the British Museum. But by the winter of 1929, Powell was again out of work.

In 1931, Powell formed a partnership with Jerry Jackson, an American lawyer from New York who had become a producer. Together, they made “Quota Quickies.” In A Life in Movies, Powell explains what these Quickies were:

“When movies became talkies, the British parliament passed a law to protect the baby British talkie from being thrown out with the bathwater by the all-conquering Yanks. It compelled a British exhibitor… to show a certain percentage of British-made products, whether the public… screamed for them or not. The aim was to keep the British film industry, which was always in trouble financially because of the overwhelming American competition, solvent by filling the lower half of a double-feature bill…”

They were the equivalent of “Poverty Row” B-films— or “potboilers” — but without Jerry Jackson, Powell never would have made it back into the film business. He made twenty films with Jerry over the course of five years until they parted in 1936. Starting in 1931 with his first credit as director, a film called Two Crowded Hours, Powell made Quickies and B-films for Warners’ British Studios as well as for producer Michael Balcon at Gaumont-British Studios. Throughout the early 1930s, Powell knew he was on the wrong track and generally referred to these films as the “trash that I was canning.”

It was during this time that he had a “dream of the Hebrides”—the islands off the northwest corner of Scotland. He became fascinated by a book about the last days of St. Kilda, which told of an evacuation of an island in the Outer Hebrides in 1930. Powell collected books about the isles. Making the Quota Quickies was never anything personal, and he did not wish to languish in B pictures. He never really wanted to go to Hollywood either even though he had contacts there. Despite being in demand for making thrillers, Powell wanted to make a movie about an island.

In 1935, Powell met Joe Rock, an American comedian turned producer. Rock agreed to finance his island movie provided he direct a mystery called The Man Behind the Mask. At age 30, The Edge of the World became Powell’s breakthrough film and a major turning point in his life. Made on the island of Foula in the Shetlands, the film told the story of how the harsh elements of nature force the locals to leave. While displaying all the natural beauty of the island, The Edge of the World was a story about the death of a community. His production team included many crew and actors, such as Finlay Currie, who would work with him on many films to come. After this great outdoor experience, Powell knew he couldn’t go back to thrillers. The film didn’t make money and vanished from circulation, but it caught the attention of Alexander Korda, who put him under contract to make films at Denham Studios. This saved Powell from the temptation of Hollywood. Korda had been a Hungarian journalist turned producer-director who had created London Films. One of his most famous productions was 1933’s The Private Life of Henry VIII with Charles Laughton.

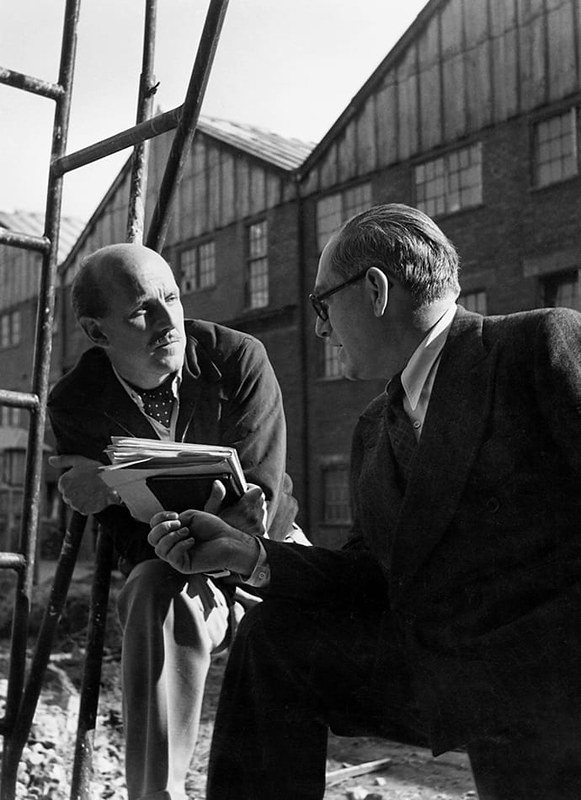

A Brief History of An Epic Partnership

As a contract director, Powell was assigned a World War I espionage drama called The Spy in Black (1939). It was based on a book by J. Storer Clouston. Prior to production, there was a meeting about the story, and Korda was a genius at story conferences. He was there along with the producer, the English writer assigned to the project, and another smaller, anonymous figure with glasses who sat at the end of the table. Korda lit a cigar and said, “Now, Emeric Pressburger has a few things to say about the script. Emeric, perhaps you will let us hear what you think about the script…” Emeric removed a small, rolled up sheet of paper and proceeded to turn the story inside out. Powell was delighted at what he heard, but the rest of the men in the room were shocked. As a result of Emeric’s changes, the filmmakers kept the title of the book and threw everything else out.

Emeric Pressburger was more than “Michael Powell’s screenwriter.” He was a filmmaker with a great story sense who elevated Powell’s career to another level. Emeric, who was born in 1902, was a Hungarian of Jewish heritage. He had gotten his start as a journalist before turning to screenwriting in the 1920s. He had been one of the highest-paid writers at the famed German UFA studio in Berlin. When Hitler took over, Emeric left Germany. According to Powell, Emeric “walked out of his flat, leaving the key in the door to save the storm-troopers the trouble of breaking it down.” He eventually made his way to Britain in 1935. Eleven years later he would become a British citizen. Emeric loved food and music, and in fact had played the violin in an orchestra in Hungary. Though Emeric’s background and personality were much different than that of Michael Powell’s—Emeric was a more private and sensitive man— the two men had a great rapport and were on the same page when it came to work.

Following The Spy in Black, Powell was one of several directors assigned to the 1940 version of The Thief of Bagdad which starred Indian actor Sabu and Conrad Veidt. Powell was responsible for several sequences including the opening arrival of the magician. This was his first color film. “Make the colour work for you, don’t start working for the colour,” he told himself. The film went on to become of the best-loved fantasies with its vibrant use of Technicolor.

Michael Powell with the stars of The Thief of Bagdad

Powell re-teamed with Emeric Pressburger on Contraband, a hugely successful wartime thriller that reunited the stars of The Spy in Black: Conrad Veidt and Valerie Hobson. Powell & Pressburger wrote the shooting script together. When World War II broke out, Korda put his studio in the service of the war effort. Britain’s Ministry of Information understood the importance of propaganda. Powell dismissed the Ministry’s suggested ideas for a film and instead offered his own. With 49th Parallel, Powell would head to Canada to make one of his greatest wartime films. With some of his Edge of the World crew in tow, Powell made a sweeping epic with stars like Laurence Olivier, Leslie Howard, and Raymond Massey. The film was shot from the west coast of Canada to the east coast. The massive amount of footage was later edited by future director David Lean, whom Powell once referred to as the “greatest editor since Griffith.” The film would win an Oscar for Emeric Pressburger for Best Original Story. All the war films that the pair initiated were original stories.

Another key figure at this time in their careers was J. Arthur Rank, a Methodist lay preacher who had become one of the most powerful figures in British cinema. Rank essentially had a monopoly on theatre chains in England, acquiring cinemas as well as studios like Denham and Pinewood. The Rank Organization, which had the best producing facilities, helped spearhead a stronger film industry in Britain. It’s been said that the new British film industry was born from an alliance between the Ministry of Information and J. Arthur Rank; the industry rose to full stature in time of war. Rank’s ultimate goal was to compete with the Americans in the international market. In regards to Powell & Pressburger, his role was basically to cut the checks and not meddle in the production of their films. They made one film at a time for Rank instead of signing any long-term contract. The Rank Organization, as many film buffs remember, features the famous trademark of the half-naked man striking a giant gong.

It was in 1942 that Emeric and Michael started their own company and received a percentage of profits from Arthur Rank. They called themselves The Archers. They shared responsibilities, especially in the writing, but Powell did the directing and Emeric assumed many of the producing chores and contributed to the editing process. The first film released under this new production company was One of Our Aircraft is Missing.

The title came from a phrase that Powell had heard all too often on BBC radio during the war: “One of our aircraft failed to return.” The opening is built around these words and is followed by an example of one of their unique title sequences. For this film, which told the story of British airmen stranded in Holland and aided by the Dutch Underground, Powell decided on complete naturalism; there is no music, for example. Also unique to the film is how the German soldiers are seen from a distance. During the evolution of the story, Emeric, who was a soccer fanatic, managed to work the game into the script, to Powell’s chagrin.

Their next enterprise was The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp in 1943, a film that lampooned the old-school military mind. Based on a cartoon character by David Low, Blimp was seen as an object of derision—the sort of figure who still believed in a gentleman’s war. Against the looming Nazi threat, the old ways of fair play and being “right” were not going to win a war. Roger Livesey (as Clive Candy) was cast opposite Deborah Kerr and Anton Walbrook. The film told the story of a friendship between soldiers, one English and the other German. It was also a love story in which Kerr played three different women throughout Clive’s life. This “intimate epic,” as Powell referred to it, was one of the more personal films they made together– and it was Emeric’s favorite.

Michael Powell had in fact fallen in love with Deborah Kerr, who was born the same day as him: Sept. 30. However, he married another woman, Frankie Reidy, in 1943. At this time, Emeric was involved with Wendy Orme, whom he would marry in 1947. It would be his second marriage. They had a daughter by the name of Angela.

The Archers had a string of successful films going. Powell, as he had vowed to do years before, had surrounded himself with the best artists around. Besides the writing talents of Emeric, he had the art direction of Alfred Junge as well as the cinematography of Georges Perinal. Powell believed Perinal, who had worked alongside French filmmaker Rene Clair, was the best cameraman he ever worked with. All these talents and many others helped make their films artistically brilliant.

However, their next film proved to be their first box office failure: A Canterbury Tale in 1944. The film, which told of contemporary pilgrims in wartime, was really about the spiritual values and traditions that the English were fighting for. The production was made in East Kent and contains many of the places and images that had been familiar to Powell in his childhood. A Canterbury Tale is one of their more eccentric films, featuring a loony squire who goes around town pouring glue in women’s hair because they are going out with soldiers. Despite the weak box office returns, the film is now recognized as one of the Archers’ finest productions.

Between films, Powell also produced, but admitted he was never very successful at it. For instance, he produced a play based on The Fifth Column by Ernest Hemingway. It was a flop and nearly bankrupted the Archers. With Emeric, Powell also produced a couple feature films made by other directors: The Silver Fleet (1943) and later, The Edge of the River (1947).

The Ministry of Information wanted another war film from the duo—one that would show the love between the English and the Americans. Emeric came up with an idea for a fantasy that would be in color. Technicolor, however, was in short supply during the war as it was needed for military training films, so instead they put the idea on the back burner and made a black and white film. It would prove to be one of their most beloved.

Emeric Pressburger wrote I Know Where I’m Going in five days. He claimed the story wrote itself. Infused with Scottish mysticism and Celtic sounds, the film was a subtle love story filmed in the Western Isles. It was the tale of a young woman, played by Wendy Hiller, who has her life all mapped out. While on her way to meet her fiancé, she becomes stranded by bad storms. She meets a young naval officer, played by Roger Livesey, who changes the course of her life. During her stay with the locals, she learns the fundamental truths of life from a people devoid of materialism. Like previous films, there is an authenticity behind the many eccentric characters seen on-screen.

Originally, Powell had sought James Mason for the role of the naval officer, but Mason was unwilling to make the physical sacrifices while on location. Roger Livesey, who desperately wanted the role, got it. Ironically, Livesey never came within 500 miles of the Western Isles; he couldn’t get out of a play he was appearing in at the time. Throughout the production, Powell used a double for Livesey for all of the exterior scenes. The striking cinematography was by Erwin Hillier, who had also shot A Canterbury Tale.

I think it’s important to discuss how these two men worked and their processes as filmmakers. In A Life in Movies, Powell writes,

“Emeric writes his stories—or he did then—with thick pencil in longhand into a quarto-size ringed notebook which accompanied him everywhere, nestling down comfortably in the big saddle-stitched briefcases that we both used, and which, besides scripts and maps, usually contained a bottle of some firewater and a couple of salami sausages. We believed in being prepared at all times, and there is nothing like a stout Hungarian or Polish sausage to give you confidence.”

Of his own methods, Powell wrote,

“According to our usual plan of work, my job was to add to and change the location sequences, bringing in all I had learnt of the authentic dialogue, atmosphere and names of the Western Isles. I ransacked Monty McKenzie’s pot-boiling novels for Gaelic phrases and idioms. As soon as I had completed the first few sequences, and numbered them with regular script numbers, I turned them over to Emeric for him to agree or disagree, or to point out to me that I had entirely missed the point of the scene.”

When they were finally able to shoot a film in color, they made what proved to be Michael Powell’s favorite movie, A Matter of Life and Death—or Stairway to Heaven, as it was retitled in America. It starred David Niven and Kim Hunter. In Powell’s autobiography, there is an entertaining section in which Powell travels to Hollywood and locates his American actress with the help of Alfred Hitchcock. A Matter of Life and Death was the story of a British airman who survives a plane crash in which he was supposed to die. However, he falls in love with an American girl and must fight for his right to stay on Earth. “Conductor 71” (played by Marius Goring) comes to claim him and bring him back to the other world. The film features wonderful performances and production design. But one of the key ingredients to the film’s lasting success is Technicolor. The real world is depicted in color while the heavenly sequences are in black and white.

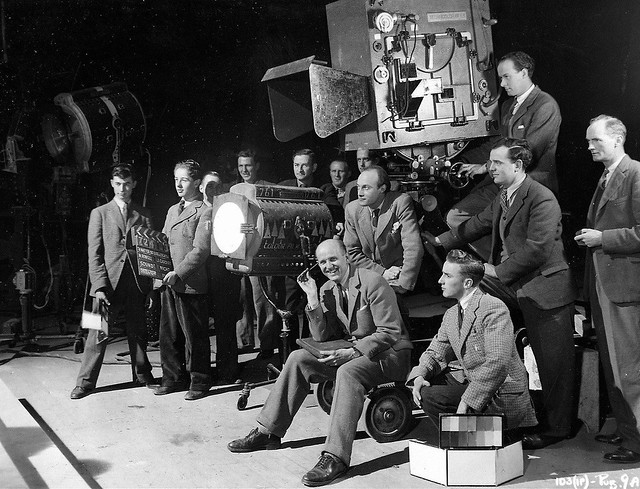

The film was shot by Jack Cardiff, who suggested the use of monochrome for Heaven. This was accomplished by printing the Technicolor film without the dyes. Powell acknowledged the “invention, imagination, and audacity” of Jack Cardiff, who was another of the key figures in the success of the Archers.

Jack Cardiff is the man that put British Technicolor ahead of America. He had been a star technician for the Technicolor company, and because of his experience with color, was hired as the chief lighting cameraman. He would photograph their next Technicolor productions in which color becomes very much a part of the story. Powell would plan his films around its use. For more about Cardiff, I recommend a documentary from 2010 called Cameraman: The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff.

Michael Powell (bottom center) with Jack Cardiff directly behind.

As we jump from one film to the next, I should say something of Powell’s process of starting a new picture. In A Life in Movies, he writes,

“Usually, it takes me three or four days to get into the rhythm of the work. In the first days of a big picture, everything seems difficult and nobody seems to anticipate anything. I am not sure of what I’m doing, and the actors are still feeling their way into the parts. I work very carefully, very methodically, and without inspiration, or so it seems to me. Usually, to my surprise, the dailies on the first and second day are exceptionally good, because they were shot with such care and fear. But I still feel everything is an effort, and I have to stop and think things out. Then, all of a sudden, something clicks, I am sure of what I am doing and so are the actors and the whole vast jigsaw puzzle of a picture starts to gel, and to acquire its own momentum.”

Their next film, the sensual and suggestive Black Narcissus, was an adaptation Powell had been nervous about tackling. Based on a book by Rumer Godden about nuns in a remote land, Powell put the design of the film in the hands of Alfred Junge and the art department. Powell had decided it would not be filmed on location in India. He would instead control the atmosphere while in a studio. Here, the Himalayas would be created through paintings on glass. This was a film where theme and color were just as important (if not more so) than plot. The director had dreamed of getting Greta Garbo for the role of Sister Superior, but instead he cast Deborah Kerr after some hesitation. Powell believed she was simply too young for the part. Black Narcissus also starred Kathleen Byron and David Farrar, who has the distinction of being the only actor ever placed under contract by Powell and Pressburger.

Powell wrote about groping his way towards a “composed” film in which the action was set to music played on the set. This is the reverse of how things are typically done when the film is scored after production. In the climactic sequence of the film, music would be the master and would dictate the movements of the characters, played by Kerr and Byron. Powell used a stopwatch to time the sequences. The film was later edited to the rhythms of the music. After this experiment, filmmaking for him would never be the same. In this dynamic, music, emotion, and acting form a complete whole. For Powell, he would continue to experiment with the composed film in his ensuing films. Black Narcissus received Academy Award nominations for both Jack Cardiff and Alfred Junge.

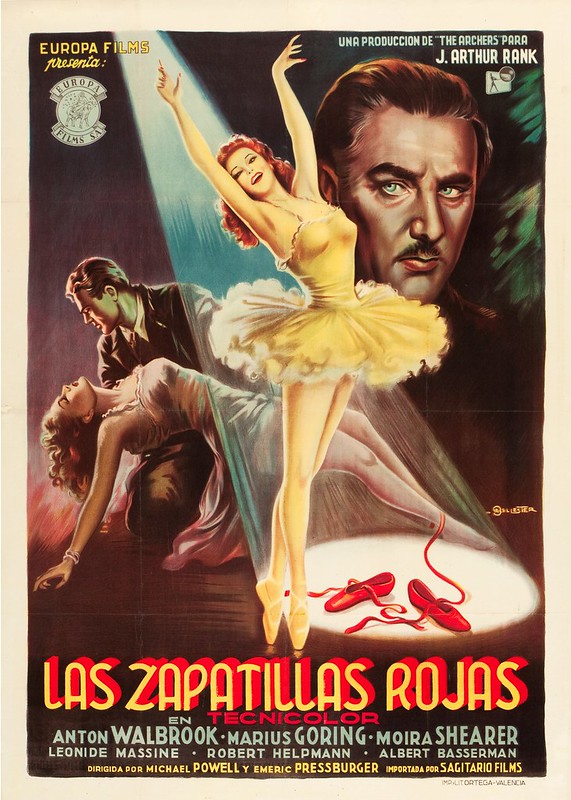

The Red Shoes (1948) had been written for Alexander Korda before the Second World War as a possible vehicle for actress Merle Oberon. It was one of Emeric’s favorite scripts, so Powell and Pressburger discreetly bought the story back from Korda. Based on Hans Christian Anderson’s fairytale about a pair of red ballet shoes and their power over the wearer, the film showed a disregard for convention by blending the art of theatre with that of film. The Red Shoes is the pinnacle of Powell’s “dream-ballet” genre and feature a 17-minute “Ballet of the Red Shoes.”

Shot on location in France in the summer of 1947, the film starred Moira Shearer who, despite a total lack of acting experience, was a natural screen presence. Shearer was a real dancer and Powell had insisted, “If a dancer doesn’t play the part, I’m not interested.” With their contacts at the Sadler’s Wells Ballet, the Archers called in artists connected with dance to choreograph and star in the film. Interestingly, there are no typical shots of a theatre audience watching the performers. Instead, the film dramatizes what characters are feeling while dancing, and we have the viewpoint of the dancer. Anton Walbrook portrayed the Svengali-like impresario who vies for Moira Shearer’s attention alongside Marius Goring, who plays her young composer lover. Powell’s message was that Art was something worth dying for.

Powell was probing deeper and deeper into his art. But in the eyes of Arthur Rank, he had gone too far. The Red Shoes was viewed as an art film with a vengeance. Rank actually walked out after seeing the completed film without saying a word. Concerned that there was no box-office name to make the film marketable abroad, Rank believed he could no longer continue with these types of films that Powell and Pressburger were making. Rank didn’t believe in the film and as a result, there was scant promotion for it. The film wasn’t even given a premiere. The British critics thought The Red Shoes was done in bad taste, particularly the film’s final moments. This would not be the last time critics would attack one of Powell’s films. The Red Shoes, however, proved to be a success when it played in New York City.

The Archers were alumni of Alexander Korda’s London Films, and in recent years Korda had tried to lure Powell and Pressburger back into the fold and away from Rank. There was competition between the two great British producers. Rank had the “Independent Producers” like The Archers while Korda had Carol Reed in his stable. Korda had also acquired Shepperton Studios and was still a major player in Britain. This desire to entice Powell & Pressburger away became a reality because of Rank’s ultimate lack of confidence in their work.

The first films they made for Korda included The Small Back Room in 1949– an excellent British film noir that recalls the German Expressionist influence on Powell– and Gone to Earth, a star vehicle for Jennifer Jones. The latter was a co-production between Korda and David O. Selznick, who later altered the film and released it in America as The Wild Heart in 1952. The original version was later restored, and Powell’s cinematographer on this film, Christopher Challis, called it “one of the most beautiful films ever to be shot of the English countryside.”

The Elusive Pimpernel, a colorful remake of The Scarlet Pimpernel that starred David Niven, followed in 1950. Powell was disinterested in the idea of a remake and had wanted to do it as a musical, but the story no doubt appealed on some level to his childhood love of adventure stories.

The Tales of Hoffmann in 1951 did for opera what The Red Shoes had done for ballet. Like the earlier film, Tales was another “composed film” in which the music was master and the performers were photographed to a playback of the musical score. This highly stylized production was based on the Jacques Offenbach opera fantastique. This filmic opera starred Moira Shearer and was the most offbeat film of their later work.

Oh… Rosalinda! (1955) was a musical comedy shot in CinemaScope and based on a classic opera but set in contemporary Vienna. Like the previous four films they had made, it was not very successful at the box office. The Battle of the River Plate in 1956, however, was a success. Shot in VistaVision, the film told the story of a hunt for a German battleship in South America. Ill Met By Moonlight, released in 1957, was another World War 2 adventure, this one about the abduction of a German general. Fittingly, these last two films were, like their first collaborations, war-time films that did well at the box office.

Powell and Pressburger would reunite in the mid-1960s and early 1970s for a couple films (1966’s They’re a Weird Mob and 1972’s The Boy Who Turned Yellow), but their best work was behind them. One of the reasons why their films with Korda never achieved the standards of their earlier work may have a lot to do with story construction. Many of their later efforts were simply adaptations– not original stories. Pressburger, of course, was one of the most original writers in England, so in some sense his talents were not being fully utilized in the 1950s. All told, Powell and Pressburger made 24 films together between 1939 and 1972. Powell was once asked what his career would have been like without Pressburger:

“I think I would have made a lot of very interesting, pictorial, but rather dull films. He brought a very necessary theatrical thrust into the films. It was my fault the partnership ended. I got bored. We still remained great friends though. I spent last weekend with him. He’s slightly frail these days. He said to me, ‘Michael, I’m four years older than you, and I don’t envy you the next four years.’”

Michael Powell made a solo career with his last great film being Peeping Tom in 1960. It was the story of a damaged young man who kills his victims with a movie camera. A work of psychological terror that turns the viewer into voyeur, the film is sometimes referred to as the first slasher movie. Though its depictions of violence ostracized Powell from the film community, Peeping Tom was later reappraised and recognized as a classic. Powell’s post-Pressburger films such as Peeping Tom are covered in detail in Million Dollar Movie, the second volume of his magnificent autobiography.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the films of Powell and Pressburger were re-examined and shown at various retrospectives and film festivals. Directors like Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese, in particular, led this campaign to give Powell and Pressburger their proper due.

In a 1986 interview with Time Out critic Trevor Johnston, Powell was asked why was the partnership with Emeric Pressburger so successful?

“Well, Emeric had the kind of mind you immediately fall in love with… The thing about Emeric was that I’d say I thought there might be a film in the phrase ‘one of our aircraft is missing’, but it would be the sort of thing I’d mention in passing and make nothing of it. I’d forgotten all about it when Emeric came back with a story where some returning pilots had to bail out in Holland and try to get home. ‘Fine,’ I said, ‘let’s write the script!’

“He’d say things like, ‘I always wanted to do a film about a girl who wants to get to an island, but then finds she doesn’t actually want to go after all.’ Why would she want to get to the island? He didn’t know. ‘Let’s make the film and find out.’ So I went away and came back with an island location that was visible but inaccessible, and that was ‘I Know Where I’m Going!’”

“I am a craftsman,” Powell once said, “and a craftsman I shall remain until I die. I know only one craft, the craft of making films. The art of telling a story to the largest audience that ever said, ‘Tell me a story!’” But Powell’s vision extended beyond the nuts and bolts of filmmaking– the mechanical aspects of putting a product together like an assembly line craftsman. He had a singular vision that wasn’t concerned with realism. He saw film as surrealism. In fact, he always believed Luis Bunuel, another filmmaker he admired, was the greater storyteller. There is no realism—only surrealism. It’s this quality that makes the films of Powell & Pressburger so enchanting. Whereas so many of today’s films are rooted in story and realism, the P&P oeuvre is pure cinema.

There was never anything ordinary about their films. They worked outside the mainstream. Whether in black and white or Technicolor, their films were lyrical, romantic, imaginative, and always creative. Sometimes they took viewers off the beaten path and into new realms, but almost always they reflected the English character. The legacy of these films extends beyond the confines of England. Their artistry left a profound mark on world cinema. With each generation, new fans discover the precision and perfection of Powell and Pressburger’s best work, and each time, the Archers continue to hit the bull’s eye.

Film historian Matthew C. Hoffman at the Northbrook Public Library.