The following is a transcript of my presentation on The Iron Horse at the Park Ridge Public Library on May 10, 2019. This was a rare Friday afternoon screening. Despite a smaller audience (compared to our Thursday night series), the film received perhaps the best response we’ve had this spring! We’re proud to have presented such a great film on this anniversary.

On the afternoon of May 10, 1869, two Americas became one. East joined West at a place called Promontory Summit in the Utah Territory. It was here where the Jupiter steam locomotive of the Central Pacific Railroad Company met the Union Pacific No. 119. After six years of construction, America had achieved the First Transcontinental Railroad. The driving of the “Last Spike”—the “Golden Spike,” as it was also known, became a national headline and a media event. The exact moment was recorded by telegraph. At 2:27 PM, the message concluded with one word: “Done!”

Today we commemorate the 150th anniversary of the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad, one of the greatest engineering feats in our nation’s history. Originally known as the Pacific Railroad, the Transcontinental was a 1,912-mile continuous railroad line built between the years 1863 and 1869. It was completed seven years ahead of schedule. There were actually three companies involved: the Western Pacific Railroad Company, which built 132 miles of track from Oakland to Sacramento, California; the Central Pacific Railroad Company, which built 690 miles eastward from Sacramento to Promontory Summit in Utah; and the Union Pacific, which constructed 1,085 miles from Council Bluffs, Iowa, westward to Promontory Summit.

President Abraham Lincoln championed the idea of the railroad despite the cloud of war hanging over the nation. He believed the project would foster unity—the kind that was lacking between North and South. In 1862, Congress authorized the simultaneous building of the two railways. It was believed that a rail line was necessary to facilitate trade and to hold the western territories. California had become a state in 1850, shortly after the discovery of gold in 1848 and the ensuing Gold Rush. The Transcontinental Railroad would reduce cross-country travel to California from several months to a week. The Central Pacific line started first. Of the two rival companies, they had the more difficult route through the mountains. The work crew was made up primarily of Chinese workers.

The building of the railroad, like the moon landing a century later, is one of the most colorful episodes in our history. It’s the sort of history that every student should know, although these days one wonders just how many would recognize names like Promontory Summit and The Jupiter. In popular culture, the event has been told and visualized a few times. Director Cecil B. DeMille recreated the event in his 1939 film, Union Pacific. But the first depiction of the railroad was the silent epic The Iron Horse in 1924. Made ninety-five years ago, the film remains one of the most breathtaking silent films of the period and one of the more accurate depictions of the actual building of the railroad.

The Iron Horse was Fox Studio’s answer to The Covered Wagon, which was a great Western released by Paramount the year before. The Iron Horse was made at a time in our country when school books told of the positive things we did. There was no better director than John Ford to tell the legend. This was to be Ford’s first major film after years spent making short features and small-scale Westerns at Universal. Most of these early silent films he made are now lost. The success of The Iron Horse would ultimately make him an A-list director.

The film was shot in the Sierra Nevada in California. The production was a major undertaking that involved the construction of a town, over 6000 extras (among other performers), and replicas of the two famous locomotives that met at Promontory Summit. John Ford prided himself in the authenticity, but despite the claim made in the film, the original locomotives from Promontory Summit were not used in the final scene. Nevertheless, it made for good publicity. Other aspects of the film, such as the depiction of the Chinese workers on the Central Pacific line, are accurate. In fact, Ford incorporated one 90-year Chinese who had actually worked on the railroad.

Ford shot a great deal of the film off the cuff and included many bits of improvised character scenes that give a sense of life among the workers. Some of these typical Ford moments include the saloon trial and the visit to the town dentist. Although the film is relatively faithful to history, the human drama that unfolds is entirely fictional. The film has its share of melodrama and contrived situations. For instance, when the hero of the film finally makes his entrance in a train being attacked by Indians, he meets his lost childhood sweetheart and the man responsible for his father’s death—all within five minutes.

The Iron Horse was written by playwright Charles Kenyon, who devised the fictional plot against the historical background. The film takes some time to build up steam with a Lincoln-inspired prologue that recalls the doctrine of Manifest Destiny. The story follows young Davy Brandon, a Pony Express rider who is enlisted by the Union Pacific to find a short cut for the railroad company. He remembers a passage through the hills that his father had shown him. However, Deroux, the man who stands to gain by having the railroad cut through his own land, tries to prevent Davy from telling anyone about his shortcut. Deroux is in fact the three-fingered renegade who had conspired with the Indians and is responsible for the death of the elder Brandon. Thrown into the mix is the requisite love interest, some misunderstanding between boy and girl, and a finale that involves gun battles, an Indian raid, and fisticuffs between hero and villain.

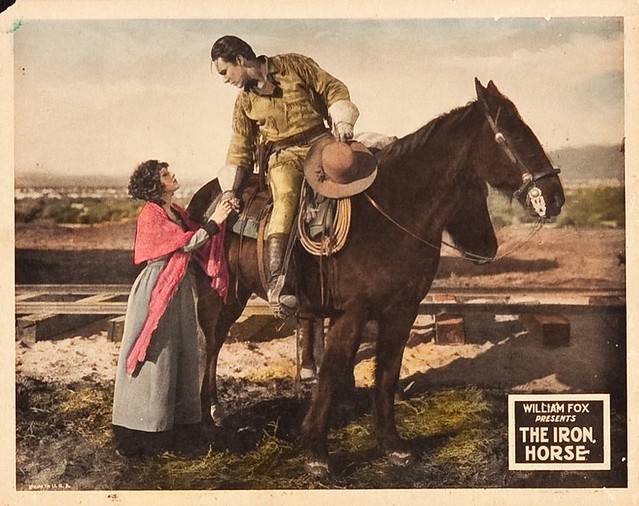

George O’Brien, who doesn’t appear until forty-five minutes into the film as the grown-up Davy, was a former wrangler and stunt man who would go on to become a Western star in the 1930s. The Iron Horse made him a star, but his most famous credit is 1927’s Sunrise, directed by F.W. Murnau. O’Brien appeared in later John Ford films as well, including supporting roles in Fort Apache and Cheyenne Autumn. More important than his film career, however, was his military service. O’Brien enlisted in the Navy during World War I and later re-listed during World War II. Madge Bellamy as Miriam was a major star in the silent era whose career faded out in the 1930s. As a freelance actress, she appeared in several Poverty Row films. Horror fans will remember her as the heroine in 1932’s White Zombie.

The Iron Horse depicts a nation united by rail and by ethnic groups: the Irish, the Italians, the Chinese, and more. And there were the Civil War veterans of both sides who stood side by side along the rails and participated in driving home the spikes. In our modern age, there are few things that unite us. In this era of historical sensitivity, it’s easy to look back and challenge the idea of Manifest Destiny that justified the taking of land for the railroad or the greed that motivated many of the self-serving tycoons and investors behind the project, or the fact that the railroad essentially cut in half the feeding grounds of the buffalo, which adversely affected the Native Indian population.

The Iron Horse is a movie that takes a broad view of the legend of the transcontinental railroad. It’s the version of history most young people knew in the 1920s. The film is the product of another time– an age where we heralded the risk-takers and the men of vision who got things done and accomplished great things. As we commemorate an event one hundred and fifty years in the past—with a movie over nine decades old– let us not lose sight of the significance of the moment. The film you are about to see is a film about man’s progress and the building of America.

A note about the screening: We are presenting the longer, U.S. version of The Iron Horse as opposed to the international version. In the days of silent movies, two cameras were set up to film both the domestic and foreign versions of a film; the latter print would be shipped overseas to the European market, such as Britain. The negative was made up of alternate takes and shots. Sometimes even the title cards were different. For instance, in the American print, the villain is known as “Deroux,” while in the other he is called “Bauman.”

~MCH