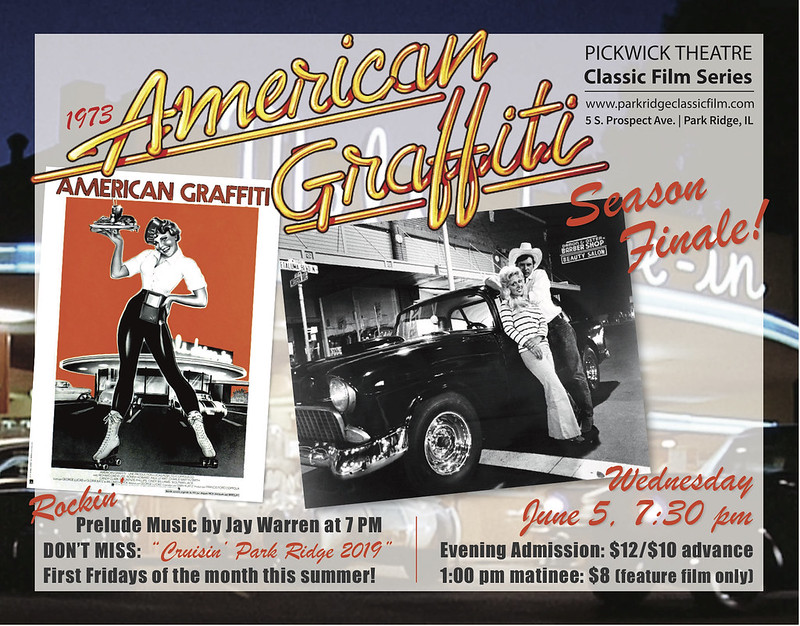

WHAT: American Graffiti (1973, DCP)

WHEN: June 5, 2019 1 PM & 7:30 PM

WHERE: Pickwick Theatre, Park Ridge, IL

WHAT ELSE: Organist Jay Warren performs pre-show music at 7 PM.

HOW MUCH: $12/$10 advance or $8 for the 1 PM matinee. Advance tickets: Click here!

“Where were you in ’62?”

Our theatrical seasons always end in May, but Season 6 has been so successful– with every screening bringing in at least 300 patrons– that we’ve been extended into June. There’s a little left in the gas tank, so what better way to welcome the summer than with a screening of George Lucas’s classic American Graffiti (1973). The film is a warm, nostalgic look at a more innocent time in our country before the JFK assassination, the Vietnam War, and the counterculture movement. This was a time of sock hops, greasers, and jukebox rock ‘n’ roll. American Graffiti was a personal film for its director because it depicted a specific time he grew up in; many of the vignettes in the film are actual experiences from either Lucas’s own life or from those he knew. As a result, American Graffiti is one of the best (and most adult) films he ever made. It initiated a ten year period of commercial success where Lucas could do no wrong either as a director or producer.

George Lucas’s first film, THX 1138 (1971), was a rather cold, dystopian science fiction film that bankrupted Francis Ford Coppolas’s production company, American Zoetrope. Francis, who was a friend and partner, challenged George to make a more normal film. Lucas set aside the science fiction and went back to his own life growing up in the 1950s and early 1960s. A product of the Baby Boom Generation, Lucas wanted to document a particular time in America when young people went “cruisin'” for girls in their hot rods. It was a distinctly American phenomenon. Lucas loved cars and racing and experienced all of it while living in Modesto, California. As a result, he could document with authority this fabric of culture. Another integral part of his life was the rock ‘n’ roll scene– in the days before the British Invasion. The film captures the relationship between teenagers and music, particularly their connection to radio disc jockeys like the omnipresent “Wolfman” Jack.

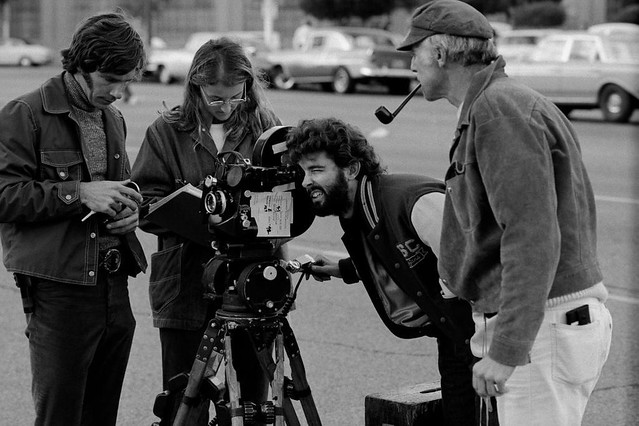

George Lucas behind the camera. American Graffiti would be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture. Lucas was inspired by his own adventures as well as by the Italian film I Vitelloni (1953).

To tell his story, Lucas enlisted the help of a couple school friends, Bill Huyck and Gloria Katz. They helped George devise a 15-page treatment which he took to various studios. He was rejected by all of them. While in Europe attending the Cannes film festival (for THX 1138), he got a deal from the United Artists’ president who gave him $10,000 to develop the screenplay. Bill and Gloria, however, had already moved onto another project and Lucas was forced to enlist another writer. The result was disappointing and read more like a teenage exploitation film than anything from his youth. Frustrated after having paid out the money, Lucas wrote the screenplay himself in three weeks. While working out the scenes, he played 45s from his own record collection and had a song in mind for each scene. Eventually, Lucas took the screenplay back to Bill and Gloria, who helped him polish it. Their biggest contribution was in helping George build up the relationship between Steve and Laurie.

The story takes place during the course of one night at the end of summer vacation, 1962. The film intertwines four main storylines: Curt has been offered a scholarship but is reluctant to leave the small town, especially after seeing the “blonde in the T-bird”; Steve is going away to college and tells his girlfriend, Laurie, they should see other people while he’s away; Terry the Toad is out in Steve’s ’58 Chevy Impala and spends an adventurous night with Debbie; and John Milner cruises the streets with teeny-bopper Carol and is challenged by Bob Falfa to a drag race. The characters are together at the beginning of the story, separate, and then return as a group for an emotional farewell.

Despite having a completed screenplay, no studio touched it. Execs at United Artists saw it only as a “musical montage” with no story. For Lucas, this was a movie more about themes than plot. The studios were also afraid of the licensing cost to secure the songs needed for the movie. In spite of these rejections, it was Universal Pictures that finally took a chance on Lucas, agreeing to finance the film provided Francis Ford Coppola sign on as producer. In the wake of The Godfather, Coppolas’s name would be invaluable in the marketing. Coppola was one of Lucas’s biggest supporters and accepted.

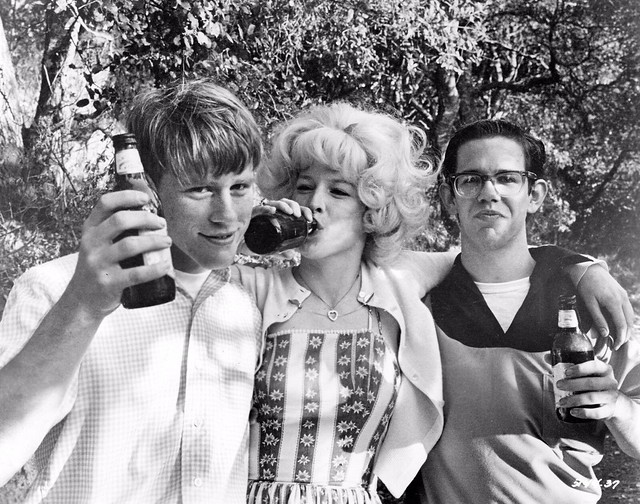

Ron Howard, Candy Clark, and Charles Martin Smith on location.

George Lucas wanted a cast of unknowns who could bring a degree of naturalism to their respective roles. With the exception of Ron Howard as Steve, most of the actors had little or no acting experience. The ensemble proved to be excellent. A lot of the credit went to casting director Fred Roos, who knew all the talented actors in town. American Graffiti would go through a lengthy casting session with many screen tests, improv tests, and rehearsals. Ron Howard was already an established child star but was making his first film as an adult. Lucas’s decision to cast Howard may have been a result of seeing him in an early TV pilot for a sitcom that eventually became “Happy Days.”

Richard Dreyfuss was an unknown who so impressed Lucas that the director offered him his choice of roles: Curt or the rather awkward Terry. Charles Martin Smith played the latter role. He was a newcomer to the business but had already appeared in films and television in his first year of acting. Paul Le Mat, a boxer, had no experience before the camera but was nevertheless given the role of Milner. Cindy Williams wanted to play Debbie, a role that went to Candy Clark, who was a model. Mackenzie Phillips as Carol was only 12 at the time, so co-producer Gary Kurtz had to agree to be her legal guardian during the course of filming. Finally, Fred Roos suggested Harrison Ford in the part of Falfa. At this time, Ford had given up acting in favor of a career in carpentry but was talked into taking the role. His one condition: he didn’t want to cut his hair short. Instead, he wore a white cowboy hat in his scenes. Also in the cast were the mythical Wolfman Jack (as himself) and Suzanne Somers as “the blonde.”

Production started in San Rafael, California, on June 26, 1972, but the city quickly changed its mind due to the disruption caused by the movie crew. Though George was able to get some footage of the San Rafael streets at night, he eventually moved the shooting to Petaluma, California, about twenty miles north. Since the majority of the scenes were shot at night, lighting (and the ability to properly get the actors in focus) became an issue. To correct this, Lucas brought in noted cinematographer Haskell Wexler as a “visual consultant.” Wexler’s assistance in regards to the lighting and camerawork (to capture the film’s strong colors) was invaluable for the crew. American Graffiti was shot with Techniscope cameras. Techniscope was a poor man’s anamorphic– a lesser (and cheaper) format that used half of the 35mm frame. The result was that it had the wide screen frame, but it created a grainier, more documentary look similar to super 16mm.

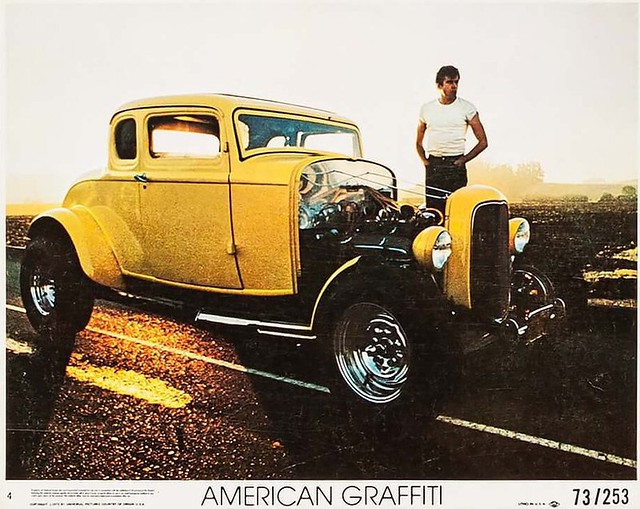

Milner’s 1932 yellow deuce coupe is one of the most famous of all movie cars. Die-cast models of the car remain bestsellers.

American Graffiti is unique in its use of sound– not just the particular songs used in the film but in how they are used. Lucas was able to get the rights to the songs he wanted–most of them anyway. (Elvis Presley is conspicuously missing from the soundtrack, which includes over forty songs). But the filmmakers created the impression that the music was played as you would hear it on the streets. With the use of speakers placed at various distances, the effect was ethereal– a strange ambient sound that was evocative of a real place. Music travels, and songs were sometimes heard in the background as though emanating from a car passing by. Sound effects were also used to create suspense in lieu of a traditional orchestral score. An example of this is the rumble of a train heard in the background as Curt hooks the rear axle of a police squad car.

The first cut of American Graffiti was three hours. Lucas himself worked on the final editing with the challenge of giving equal time to all the storylines. Though it was unconventional storytelling in 1973, so much of today’s television is done in a similar manner with cutting back and forth between characters. When the film was eventually completed, Universal was still not happy and insisted on further cuts as well as a title change. Lucas held firm to the title he wanted. The studio also threatened to release it as a TV movie, but word of mouth was so strong among those who previewed it that the film was released theatrically and became a sleeper hit.

American Graffiti, although made for only $770,000, took in $140,000,000 at the box office and became one of the most successful films of its time, paving the way for the “summer blockbuster” that George Lucas and Steven Spielberg eventually created. The film resonated with audiences and critics alike and remains one of the most loved of all of Lucas’s films. There have been countless coming-of-age comedies since, usually relying on sex or gross-out comedy. But American Graffiti is ahead of the pack, racing along the two-lane blacktop ahead of the competition. Although set in a world that is now foreign to many with mating rituals incompatible with today’s #MeToo Movement, the film’s main themes remain universal. The idea of leaving home and moving on from the things that hold us back are rites of passage that most of us face. It would be a recurrent theme with Lucas– one that would manifest again in his next film, 1977’s Star Wars.

We’ll meet you at Mel’s Drive-In– or on “Paradise Road”!

For much more about the history of this great film, visit Kip’s American Graffiti Blog.

~MCH