“There seemed to be some indefinable quality, some unique combination of appearance, voice, quiet humor, or personal projection that made us pay, by the millions, to spend some time with him; not to be preached at or instructed by, but simply to be complimented by his example of what qualities the human species is capable, even the least of us. Perhaps this is the heritage that Colman offered: that it is most important to not only reveal what man is, but what man can be.” — George E. Schatz

Ronald Colman (February 9, 1891 – May 19, 1958) has always been my favorite actor. I say that knowing full well that nine (perhaps even ten) out of ten people on the street right now would be hard-pressed to name a Colman film. His most popular film, though hardly his best, is undoubtedly Random Harvest only because TCM plays it so often. I had been aware of his name ever since I was a child because my dad would often do his impersonation of Colman’s voice: “Ah, Benita, if the stars should shine, as they shine in your eyes tonight, I could live but for eternity.” (Whether or not that was actually a real Colman quote, I’m not entirely sure.)

Then one night on television, I was watching “Entertainment Tonight” and there was film historian Leonard Maltin showing a clip of Colman in 1929’s Bulldog Drummond. (This was in the days when these types of evening entertainment shows recognized our past and actually had segments on classic movies.) I was immediately struck by Colman’s coolness under pressure. It was a scene in which the villain was threatening Bulldog Drummond. “If you move a muscle, I’ll shoot.” Drummond hangs up the phone. “Then I certainly shall not move a muscle.” The movie is probably too static to be of much interest to modern audiences, but I love it, and that is primarily because of Colman’s enthusiasm in the role.

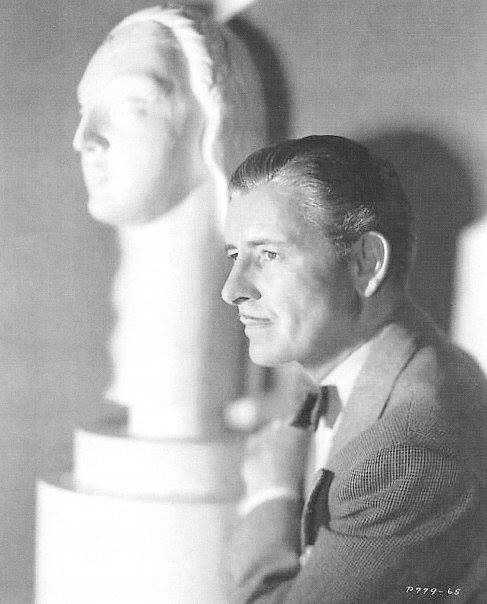

Colman had been a major star in silent pictures before Bulldog Drummond, which was his first “talkie.” He successfully made the transition to sound because he was blessed with perhaps the most melodious speaking voice in movie history. Although known for his voice, some of his best acting was done without using it. His technique– honed in the silent era– was subtle, and some of his best moments on screen came through the power of suggestion. A close-up could speak volumes and reveal so much. In real life, Colman spoke very little, at least publicly. But he saved his best for his audiences. It was the best version of himself that he projected.

A montage I created of Ronald Colman’s silent movies…

Sometime in the mid-1990s, I was going through film magazines which the Columbia College Chicago school library had on file, and I came across an article on Colman. It was one of those newspaper format magazines that dealt with vintage movies. It may have been Classic Images. I photostatted the article the best I could (given its tight binding), and I discovered that the author had the same appreciation for Colman that I had– but with a singular fascination with Colman’s voice. The author’s name was George E. Schatz, a World War II veteran who lived in Highland Park with his wife, Lois.

This suburb was not terribly far from where I lived, so I was able to track George down easily enough. He invited me over, and it was then that I realized the full extent of his interest in Ronald Colman. Never before had I seen a collection like his– photo albums the size of telephone books on every Colman feature, each containing hundreds of movie stills I had never seen before. Some of which I haven’t seen again. Vintage posters hung on the wall beside a framed letter from Frank Capra. And he had almost all of Colman’s radio appearances either on tape or vinyl. Beyond his Colman collection, I saw another part of his life on display in the basement. George had been a bombardier on a B-17 Flying Fortress, having flown 32 missions as part of the 600th Squadron. There were various artifacts from his war years he was proud to show off, including an apparatus that was part of a bombsight from his plane. Mr. Schatz, the ultimate collector, was very dedicated, and he was very generous with me.

In Colman’s memory, I administer the Ronald Colman Appreciation Society on Facebook, which was created in 2008 and inspired by George Schatz’s original Appreciation Society. His group, created in the days before social media, included such charter members as filmmaker Kendall Miller and authors R. Dixon Smith and Sam Frank. As of 2021, the online version of the RCAS has nearly 2,000 members. Some of the frequent contributors include Gail Crowley, Sheila Bryans, Jay Ashby, and Sandra Necchi (all moderators), as well as devoted fans like Ilene, Julianne, Sally, Helen, Shaun, Richard, Jim, and so many others. (Our photo gallery, the largest on the Internet devoted to RC, is the result of so many contributions.) And, of course, we are grateful to have Kendall Miller as our resident Colman authority. Why so many members for an actor who made relatively few films? What more was it about Colman that remains so appealing?

Colman’s screen persona projected qualities we should all strive for. Yet sadly, many of his traits– his elegance and savoir faire, for example– have fallen out of fashion in a society that, at times, borders on the barbaric. Part of the fascination for me has been the image of Colman as the chivalrous, self-sacrificing hero. Both on and off screen, he was the quintessential gentleman. His motto could’ve easily been: to thine own self be true. He was that rare breed of actor who, through the good humor he projected, made audiences– this one, particularly– feel good about life. Whether he was quoting poetry as Francois Villon or simply walking down the street with a dog in his arms, he could make you smile and change your outlook. Author Lawrence J. Quirk once said of him, “Colman alone gave the world, through the medium of his films, that combination of exceptional good looks, poetic grace– and a strong tinge of mysticism in his aura that enchanted and intrigued millions.”

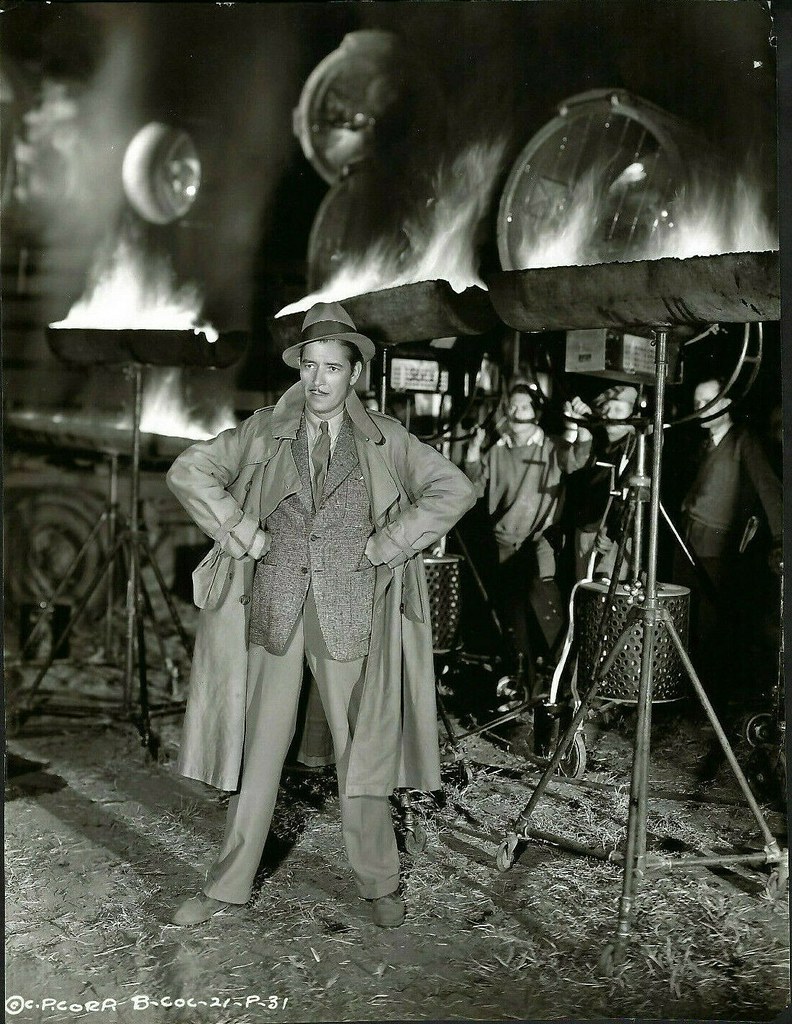

Whether it’s A Tale of Two Cities (1935), or The Prisoner of Zenda (1937), or Random Harvest (1942), watching a Ronald Colman movie has always been an event for me. To really appreciate Colman and understand the qualities that made him so special among Hollywood’s leading men, I think it’s important to re-introduce the film that best represents the Colman image. When I had the opportunity to manage a revival house for the first time, there was one title at the very top of my list. It remains one of the movies I am most proud of screening. Lost Horizon (1937) is a film that shows how we, collectively, can be more than what we are now. It’s a movie that makes us believe in a transcendent humanity in which people can rise above the ugly parts of society.

Lost Horizon, Frank Capra’s masterpiece, is a beautiful film in many ways. In addition to Colman’s presence, the film stars Jane Wyatt, John Howard, H.B. Warner, Edward Everett Horton, Thomas Mitchell, Isabel Jewell, Margo and Sam Jaffe. In it, Ronald Colman portrays Robert Conway, a visionary diplomat who glimpses the eternal in Shangri-La– a place, as author James Hilton wrote, “touched with the mystery that lies at the core of all loveliness.”

On October 5th, 2002, I presented Lost Horizon at the LaSalle Bank revival house in Chicago. It was, in fact, the first film ever shown in the 35mm format at the bank. The audience response that night was wonderful. In the brochure for the film series that season, I had George Schatz write about the film. Given his previous writings on Colman coupled with his profound knowledge on Lost Horizon, he was the only person I knew who could eloquently express why this was such an exceptional movie. (The Ronald Colman Appreciation Society would help get it added to the National Film Registry in 2016 with a write-in campaign.) Sadly, Mr. Schatz passed away in 2015 at the age of 96, but nearly twenty years after he first penned it, I re-post his words (unedited) as a special introduction to the film that best defines the Colman mystique.

***

There is a rare fruition, a quality of distinctive elements blending together as rewardingly as with a vintage wine, that transforms Frank Capra’s Lost Horizon into that form of anticipation and deeper impact we sometimes experience with a beloved opera or symphony. Our newer DVD technology offers us the choice to skip to favored scenes or musical numbers, but we think you’ll find that there is such an insistent procedural relationship, such inevitability of scene to scene, with their additional gifts of visual and aural beauty in this classic film that you’ll not want one instant out of its flowing place.

Capra could not have fully known, as we are fortunate enough to appreciate in 2009, was how truly timeless Stephen Goosson’s set designs for Shangri-La would prove to be, or that Dimitri Tiomkin’s musical score lives as a multi-themed masterpiece that gives each scene its deserved distinction. What Capra did know was that there was only one actor to truly embody and represent the major role of Conway: Ronald Colman. Time has also revealed that Colman, beyond his enduring 3-decade handsome ‘leading man’ appeal and ‘Best Actor’ nominations over an eighteen-year period, proved to be, in his personal life as well as his characterization in this film, as close to being a true Renaissance man as we may hope to find in the real world. His exceptional clarity and quality of speech could offer even ordinary sentences a poetic lift, but given the Capra-Robert Riskin script Colman enjoyed here, you might well find phrases and content both affecting and memorable.

There is a type of ‘critic’ who seem to delight in stealing and repetitively using the term “Capra-corn” with a ill-earned smugness, which hardly accurately describes the immigrant boy whose flowering and insistent intellect earned him a Degree in Engineering, whose bright comedic wit won a career writing scripts for silent films, and who not only served his United States during World War II directing the Why We Fight series of films, but carefully gathered a collection of beloved rare books worthy of a museum.

And if those same critics seem to dismiss Capra’s Lost Horizon as a “fantasy,” they are correct only in one instance: the extended-life span is contrary to Earth’s environmental realities. But even here, the James Hilton book and the Capra-Riskin script cautions us: when Conway is offered this extended span of active life, he demures: “It must have a point. I sometimes wonder if life itself has any.” This is hardly the substance of a mindless sugar-coated going-to-the-seashore escapism.

In all other respects this story is of the Earth, fully within the limits of our own humanly achievable. It does not depend, as would most “fantasies,” upon metaphysical, supernatural, or extraterrestrial interventions. While we readily acknowledge that the very nature of Shangri-La demands an exotic location, this must be understood in the context of its time: the author of the 1933 novel (as, of course, would be the writers of its 1936 screenplay) was only too well aware of the threatening tentacles of Hitler’s voracious Nazi intentions; therefore, Tibet seemed to provide a site not only excitingly remote and mysterious in which to place Shangri-La, but also so as the High Lama states: “We may expect no mercy, but we may faintly hope for neglect.” It is here that we believe a most important distinction was made by the Capra-Riskin screenwriters: they changed the novel’s “our” books and music, to “their” or the entire outer world’s accumulated scientific and cultural knowledge, not as an ‘elitist’ Utopian society, but hoping only to act as a safe haven, a temporary repository, until a war-mad world could retrieve it if and when peace finally returned.

In a 2002 Earth, where not even Tibet remains removed from a satellite digital pinpoint, every local library with interlibrary and computer resources can provide a similar Shangri-La-like stunning wealth of knowledge to our individual selves! But in that 1933 and 1937 world, that fragile story depends upon our believing that Conway believes in Shangri-La and its humanitarian purposes, and, when we witness that Capra and Colman so obviously believe in its rewarding totality, you feel free to, as well!

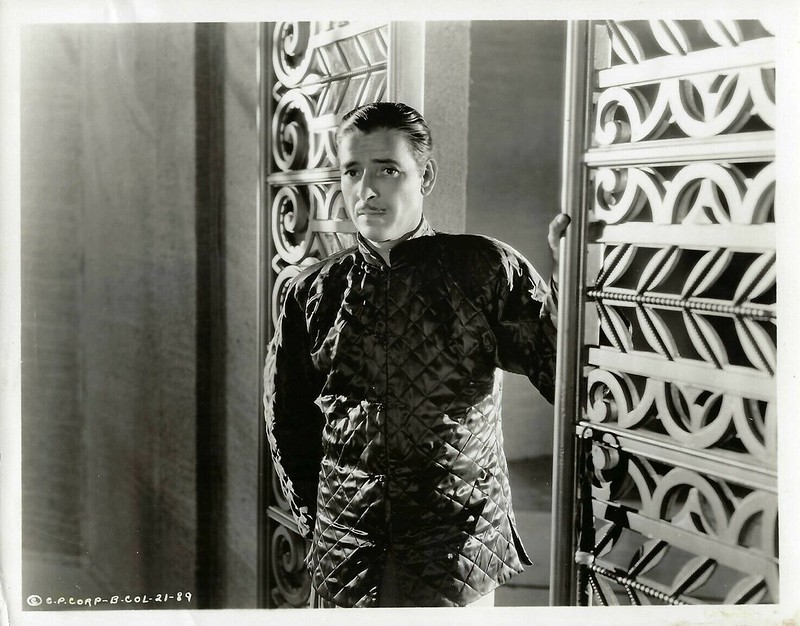

Ronald Colman as Robert Conway…

***

This year Ronald Colman turns 130. Yet with each passing year, fewer and fewer people remember his name. Those that do usually spell it “Coleman”! But we hope that within each generation, there are at least a few who will look back and discover the Colman magic. In our modern society, we are increasingly inundated with fleeting entertainments and the ephemera of pop culture. As culture becomes less educated and less discerning, it is doubtful Ronald Colman will ever have a wide appeal. In addition, audiences have become increasingly jaded and cynical. With all the issues going on in the world, what possible relevance could a cultivated, English gentleman born in the 19th century have now?

Colman’s legacy is tangible (through film preservation)– and permanent (in its influence)– and ready to be passed down. We might not all be as adventurous as Rudolph Rassendyll or as scholarly as William Todhunter Hall, but the core of what he projected on the silver screen, on television and on radio is universal. Common decency, courtesy towards others, respect– and the belief that every person be given a sporting chance in life in order to reach his or her potential…. these are things the Colman Hero would have certainly championed. These qualities are just as important in 2021 as they were when Colman was alive, and they are needed now more than ever.

Until the end of time, we will never have another Ronald Colman to inspire us. There was only one, but he had many imitations. And yet, no matter how much you elaborate on why he was so unique, it’s difficult to build that fan base with younger audiences. There needs to be a readiness in the individual to appreciate Colman. Viewers need to seek him out. Those that do will find great reward in the effort. Ronald Colman’s screen characterizations, like Robert Conway in Lost Horizon and Sydney Carton in A Tale of Two Cities, are eternal. These roles embody the very best of man and human nature– our hopes and dreams. His movies, reminders of those aspirations, will always be there in some form waiting to be re-discovered– like Shangri-La itself.

~MCH

A letter from George Schatz in which he included me in the RCAS…