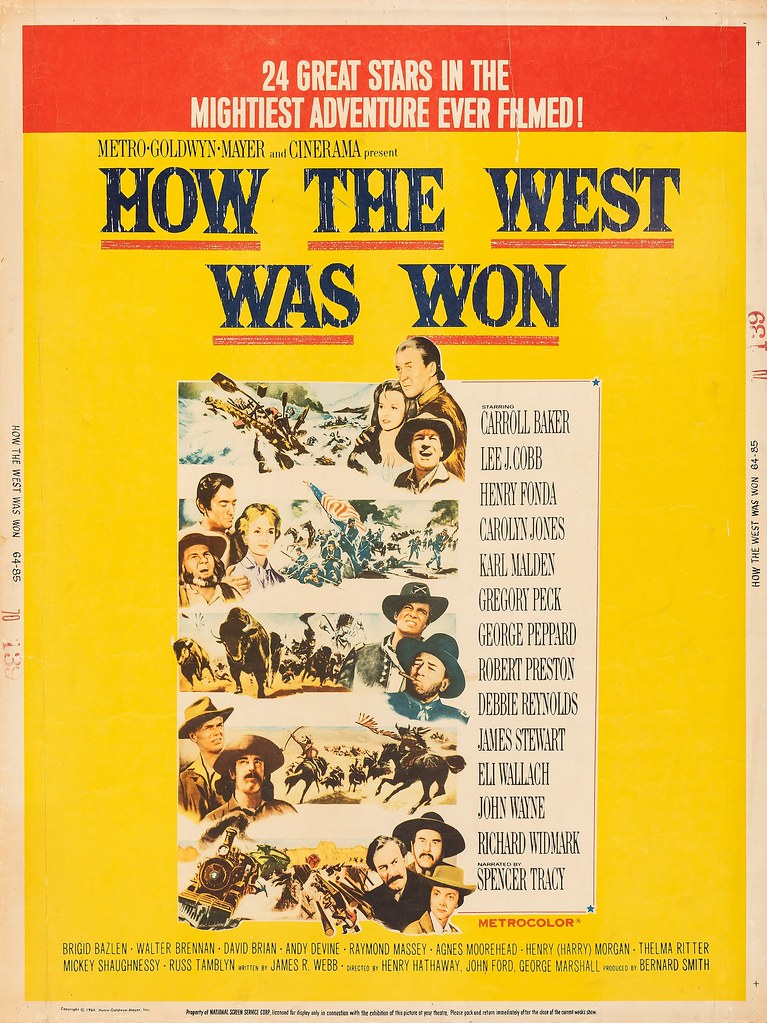

WHAT: How the West Was Won (1962, DCP, 164 min.)

WHEN: January 10, 2024 1 PM & 7 PM

WHERE: Pickwick Theatre, Park Ridge, IL

WHAT ELSE: Pre-show music by organist Jay Warren at 6:30 PM.

HOW MUCH: $12/$10 advance or $10 for the 1 PM matinee

For advance tickets, Click Here!

Those who experienced How the West Was Won in 1962 in Cinerama (as it was intended), never forgot the big-screen thrills and visceral impact of venturing down the rapids on a flimsy river raft, riding with the Indians as they charged on horseback, being overrun by a buffalo stampede through a railroad encampment, or having the point-of-view of a locomotive on its short-lived trek through the desert. Cinerama was the IMAX of its day– only better.

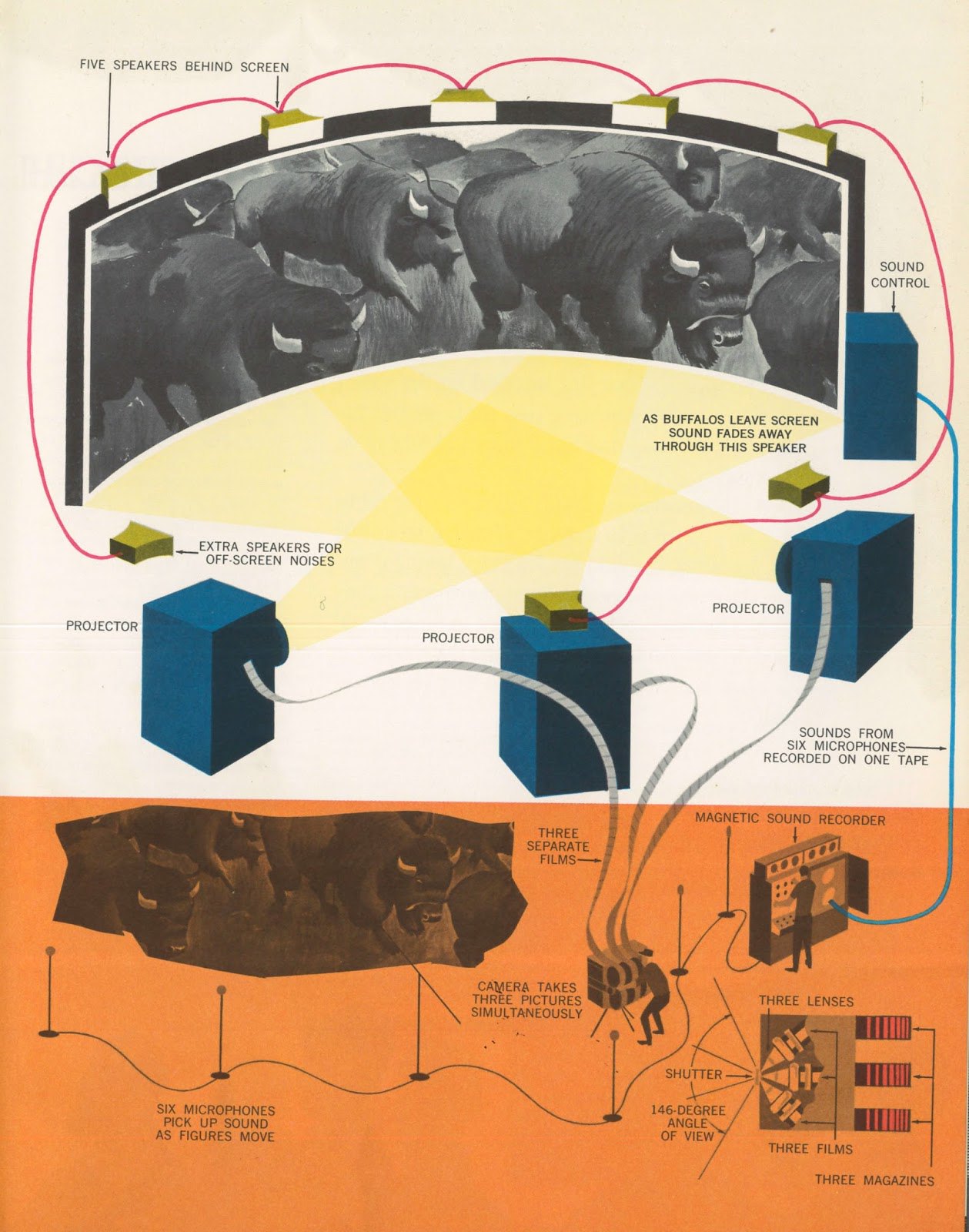

How the West Was Won is one of two feature films made in the original Cinerama process; the Cinerama camera was essentially three cameras in one, and it recorded three images simultaneously. These strips of separate film were later projected in specially-designed Cinerama theatres. These theatres featured three projectors and a curved screen with louvered panels (to eliminate cross-light). The film’s images were projected at the same angle of view in which they were photographed.

Today, except for revival theatres 2,000 miles away, no one projects in Cinerama. However, the Pickwick Theatre still has one of the largest movie screens in the Chicago area, and we thought this would be an ideal film to showcase on the MEGA-screen. The film’s compositions were intended for the largest screens in the world, and although our showing lacks the immersive quality of pure Cinerama, we are nevertheless presenting one of the outstanding Hollywood spectacles as it was meant to be seen– on a big screen.

The origins of Cinerama go back to World War II when inventor Fred Waller developed the technology for gunnery training. With sound pioneer Hazard Earle Reeves, Waller adapted the process for theatrical exhibition and in 1952, the world experienced This is Cinerama. The intent was to recreate the full range of human vision on screen– or 146 degrees of arc when projected (suggesting peripheral vision). It was coincidence that the word Cinerama was an anagram for American.

With showman Lowell Thomas, salesman Michael Todd and producer Merian C. Cooper at the helm, This is Cinerama became a successful demonstration of the medium’s potential. It was a tremendous hit in the early 1950s and inspired movie studios to come up with their own widescreen processes, such as CinemaScope at Twentieth-Century Fox. Despite the sensation it generated, This is Cinerama was essentially a travelogue, as were the Cinerama films that followed including Cinerama Holiday (1955), Seven Wonders of the World (1955), Search For Paradise (1957), and South Seas Adventure (1958). How the West Was Won, by contrast, would be the first dramatic film to use Cinerama. The film actually opens with an aerial shot– depicting a flight across America– that is an outtake from This is Cinerama.

With the MGM studio on the doorstep of producing the first Cinerama feature (they were in talks to do several movies), singer Bing Crosby was developing a television program called How the West Was Won. It was based on a Life magazine article that condensed the westward movement in our nation’s history. Crosby had previously recorded an album of the same name with Rosemary Clooney, featuring period folk songs of the era. He approached MGM and sold the studio on the idea of turning How the West Was Won into its first Cinerama film. Initially, Crosby was to be involved as the narrator of the film.

The project was announced in the summer of 1960. At that point, it was called The Great Western Story and dealt more with historical figures of the Old West. At the time, it was determined that proceeds from the film would go to St. John’s Hospital. This goodwill gesture served as an incentive to attract major stars; they might’ve been more willing to take less than what they typically commanded. Irene Dunne, who was president of St. John’s, was expected to appear in the film along with Bing Crosby, but neither did.

With Bernard Smith as producer, James Webb was given the task of developing a script and personalizing the history. According to Smith, “It is essential for our purposes that virtually the whole movie be shot outdoors. Throughout the movie, one of the basic themes is to show little people against a vast country– huge deserts, endless plains, towering mountains, broad rivers. We want to capture the spirit of adventure, the restless spirit that led men and women across the country in the face of many difficulties and dangers.” James Webb embodied this spirit with five sections that focused on the westward expansion of the 1830s, the California gold rush, the Civil War, the transcontinental railroad, and the days of the outlaw.

This sprawling tale about the winning of the West covers three generations and roughly fifty years (1839-1889) in our nation’s history. “The Rivers” follows the pioneering Prescott family as they make their way westward on the Erie Canal. Along the way, they meet a mountain man, Linus Rawlings, who later rescues them from a band of river pirates. After a river accident kills the parents, the Prescott sisters split up with Eve choosing to stay in place and farm the land and Lilith heading east to find a career as a Music Hall performer. Lilith meets a tinhorn, who accompanies her over “The Plains” after she inherits a gold mine. “The Civil War,” the third segment, follows Eve’s son Zeb, who enlists in the Union and sees action at the Battle of Shiloh. After the war, as a member of the U.S. Cavalry, he helps in negotiations between the Native Indians and “The Railroad.” However, nothing can stop the march of progress and the ambitions of the empire builder. The final segment, “The Outlaws,” involves Zeb, now a marshal, confronting a band of renegades led by Charlie Gant. Zeb’s family also meets Aunt Lilith, who is now a widow. She has returned to the West to have Zeb oversee her Arizona ranch.

In October of 1960, George Peppard was announced as the star (portraying Zeb Rawlings), and by April of the following year, John Wayne and Spencer Tracy were expected to play Generals Sherman and Grant in a segment directed by John Ford. Other stars included Carroll Baker (as Eve), Lee J. Cobb, Henry Fonda, Carolyn Jones, Karl Malden, Gregory Peck, Robert Preston, Debbie Reynolds (as Lilith), Thelma Ritter, James Stewart (Linus Rawlings), Russ Tamblyn, Eli Wallach (as Charlie Gant) and Richard Widmark.

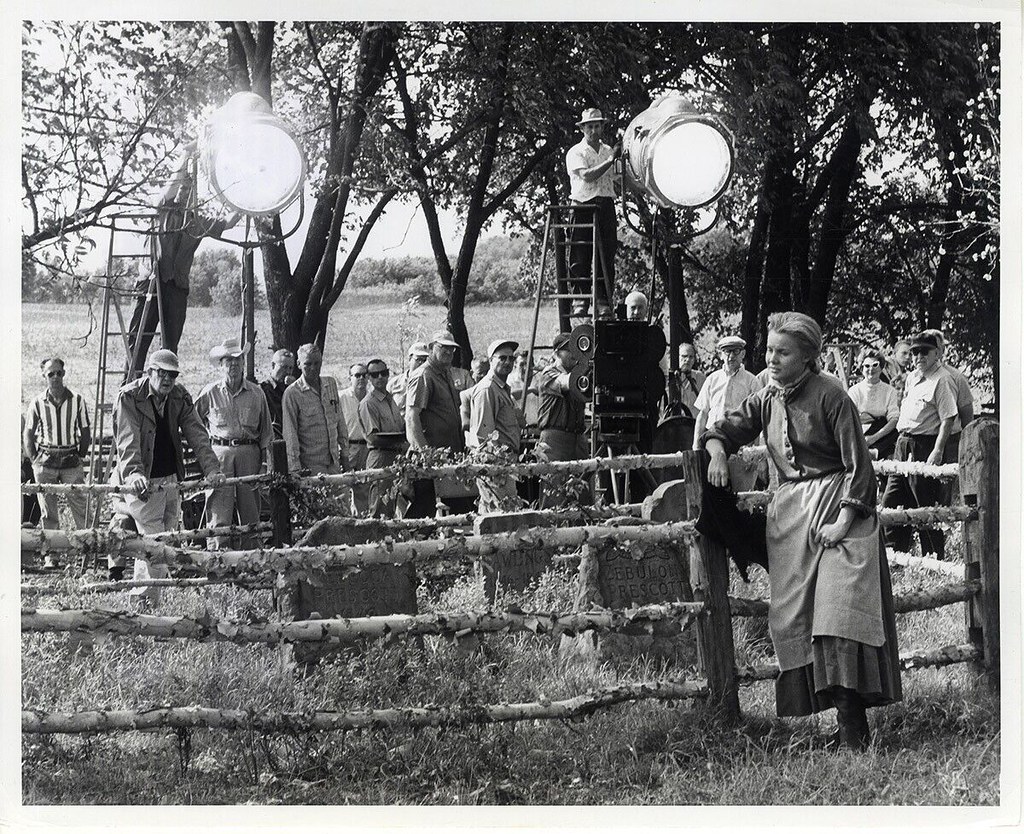

James Stewart and Carroll Baker

Filming began in May 1961 with John Ford working on location in Kentucky. His Civil War segment would be his only contribution and featured John Wayne as General Sherman and Harry Morgan as General Grant. Originally, the Grant role was to have been played by Spencer Tracy, who was unavailable (although he still narrated the film). Henry Hathaway directed three of the five segments: The Rivers, The Plains, and The Outlaws. George Marshall directed “The Railroad.” Hathaway’s influence, however, extended into Marshall’s segment as well. Additionally, director Richard Thorpe worked uncredited on the film. It was the producer’s idea to have Hathaway, Ford and Marshall– three old pros– working on this distinctly American story.

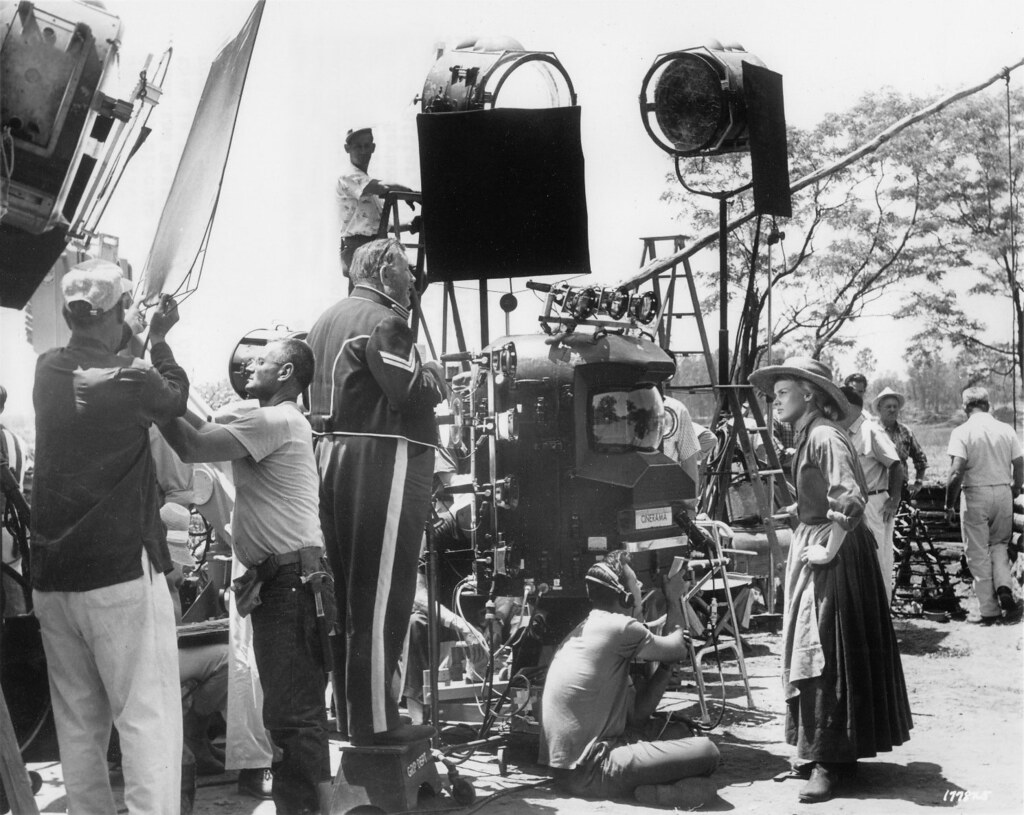

All the directors became frustrated with the Cinerama process, especially Ford, whose usual film-making practices, such as standing beside the camera, were hampered. It was Henry Hathaway, however, who put in the time to learn the intricacies of Cinerama. It was not easy for the filmmakers or the cast. The camera was a three-lensed behemoth that weighed 800 pounds. The mechanism was comprised of three 35mm cameras with 27mm lenses– all running simultaneously and sharing one shutter. Each camera lens, set at 48 degrees from each other, recorded a third of the screen. One camera pointed straight, one pointed to the left and one pointed to the right. The camera was able to take in a field of view 146 degrees wide and 55 degrees high. As with the This is Cinerama camera from a decade before, it was impossible to film close-ups. If the camera was closer than 18-inches from the subject, the actor would wind up appearing in multiple panels.

A problem for actors was that their eye lines did not always match if one character was photographed in one panel and the other actor in another. Actors would have to be instructed where to look so that when the film was later projected, it would appear as though they were speaking at eye level. One easy solution for the director was to keep the actors speaking to each other in the same panel. The joint lines, where the panels met, were always obvious on a bright background. These were sometimes craftily hidden by the director’s compositions, such as having trees where the joint line would typically be seen.

Helping the directors through this arduous process were some of the finest cameramen in the business. These included William H. Daniels (who had been Greta Garbo’s personal cameraman), Milton Krasner (The Set-Up, All About Eve), Charles Lang (The Big Heat, The Magnificent Seven), and Joseph LaShelle (who worked with Otto Preminger and Billy Wilder). Given the fact that the cameras were pointed in three separate directions, lighting a scene was particularly difficult. The cameramen had to know exactly how to use back light, a cross light, and a flat light in order to have uniform lighting across the entire frame.

Behind-the-scenes with Andy Devine (in Civil War uniform) providing a point of reference for Carroll Baker. Note the giant Cinerama camera (in a sound blimp) in front of her.

The performances that were captured vary in length throughout the film. Twenty-nine-year-old Debbie Reynolds gives it her all throughout the film, especially during her musical numbers. James Stewart’s appearance as the mountain man “always going to see the varmint” is the highlight of the opening segment, which also features a villainous turn by the great character actor Walter Brennan (as the head of a family of pirates). Stewart had worked with Hathaway years before in the film noir classic Call Northside 777 (1948).

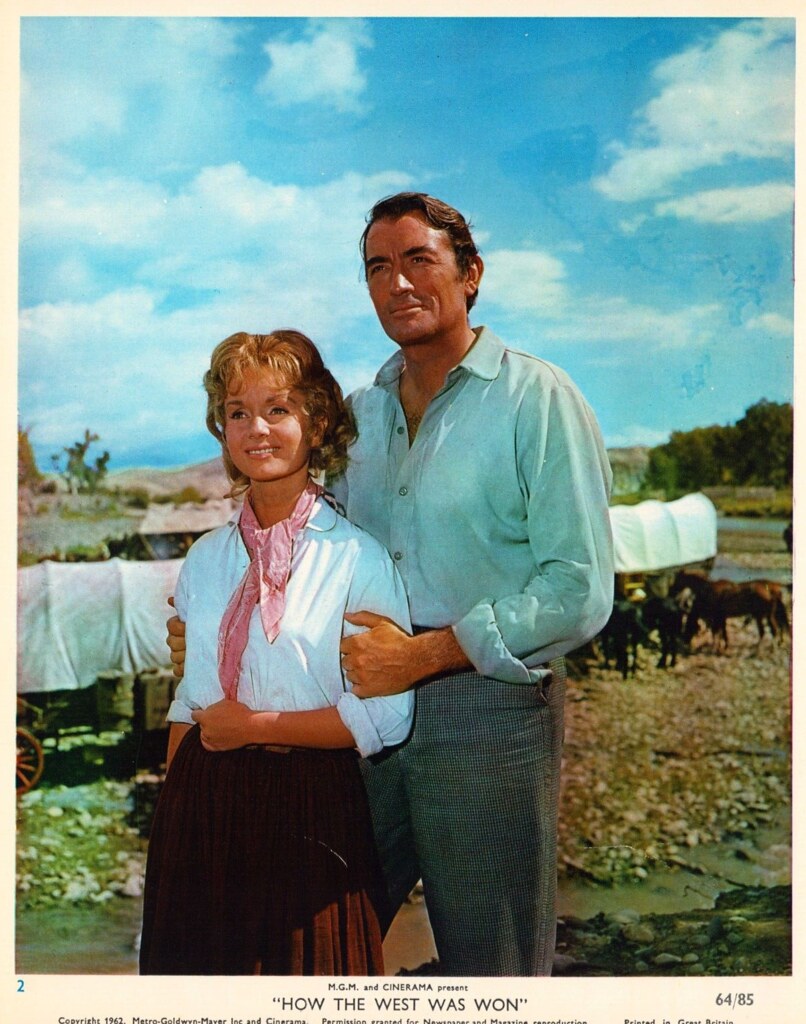

Gregory Peck, like Stewart, was a veteran of many Westerns, although in his case he did not particularly care for the Cinerama process. He never considered How the West Was Won as one of his better roles, although he is quite effective in it. Henry Fonda is equally memorable as the buffalo hunter. However, it’s George Peppard who has the most to do, and it’s really his film. Though Peppard had made an impression a year before in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), the role of Zeb Rawlings suited him far better. Interestingly, his improvisation during one scene didn’t immediately impress John Ford. During the porch scene with his “mother” –Peppard was actually three years older than Carroll Baker– he does an off-script imitation of Jimmy Stewart’s drawl. According to Peppard, his intent was to remind audiences who his father was in the context of the story. Another improvisation that met with greater enthusiasm came in the final segment where Eli Wallach makes a hand gesture as though to suggest he is gunning down Zeb’s children. Hathaway loved it and kept it in the final film.

John Wayne is essentially playing… John Wayne playing General Sherman. His cameo is more about name value than it is about authentic characterization. But when John Wayne enters the doorframe as the Union general, you are seeing a genuine movie star appear, and that alone is worth the price of admission. The smallest cameo in the film, though, belongs to Raymond Massey, who plays President Lincoln right after the film’s intermission. He is first seen standing by a window (which, as the film played, allowed for the theatre curtains to re-open). He then takes a seat at his desk before the moment transitions into the next scene. Massey had played Lincoln before, most famously in the 1940 film Abe Lincoln in Illinois. [There are other fine character performances throughout the film, but some of us film buffs have wondered how the West could’ve possibly been won without the likes of Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott! Or, to add some cowboy authenticity, Colonel Tim McCoy! Google him.]

Some of the locations used in How the West Was Won included the Cumberland River, Kentucky; Custer State Park in South Dakota; Silverton, Colorado; Perkinsville, Arizona; Monument Valley, Utah (a famous John Ford location that was not shot by Ford here); and Wildwood Regional Park in Thousand Oaks, California, among others. Those in downstate Illinois might recognize Cave-In-Rock State Park, along the Ohio River, which was used for the scene where Linus Rawlings is tricked by pirates.

Debbie Reynolds and Gregory Peck

One of the delights is the film’s musical score by the legendary composer Alfred Newman. Newman, whose career included 45 Oscar nominations and 9 wins over the course of 200 film scores, was known especially for his mastery of string instruments. How the West Was Won is filled with folk songs arranged by Ken Darby and beautifully orchestrated by Newman. In addition to the title song– a rousing, classically American anthem– one of the highlights is Debbie Reynolds’ rendition of “A Home in the Meadow” performed to the tune of the English ballad “Greensleeves.” This is one of three songs that Debbie Reynolds sings in the film. The others being “Raise a Ruckus Tonight” and “What Was Your Name in the States?”

Filming was completed by January of 1962. How the West Was Won was a success for MGM. It played in theatres for months and, in some instances, for years. From a budget of $15 million, the film was able to gross $50 million worldwide. How the West Was Won had a profound impact on those who saw the film in Cinerama, whether it was in its initial roadshow exhibition or later when it played all over the States. The Pickwick Theatre’s very own Jay Warren distinctly recalls seeing the film in Cinerama at the McVickers Theatre in Chicago back in the early ’60s.

The film won Academy Awards for Best Writing (James Webb), Best Film Editing (Harold Kress) and Best Sound (Franklin Milton). How the West Was Won was successful in how it incorporated music but also in knowing when to use natural sound only. One example of this is the family journey down the rapids. The river sounds are more dramatic than any musical underscoring that might’ve been used. Though it did not win, How the West Was Won was also nominated for Best Picture and Best Music.

Despite the box office success, this incarnation of Cinerama failed because it was too costly. This was due to the expense of the oversized camera, all the film that was needed– three strips of film running through the camera– the potential technical problems both in the shooting and in the projection, and the extravagant cost for theatres to present these films properly with the three projector set-up. The number of theatres around the country that could project films like this were limited. Fifty years later, there were only a handful in the country that could, most famously the Cinerama Dome in Los Angeles. Not surprisingly, there was only one other feature film made in original Cinerama: The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (also in 1962).

The name “Cinerama” remained, but instead of three-lensed cameras, filmmakers transitioned to one camera with a 70mm lens. Later releases like the faux-Cinerama It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) were filmed (in Ultra Panavision) with just the one camera, although they were still advertised as being made in Cinerama. It should be stressed that, aside from the Brothers Grimm, How the West Was Won remains the only three-panel Cinerama film. Home releases of the film make it clear that it was shot differently than anything that had come before. (The closest any filmmaker ever came to this was Abel Gance back in the 1920s. His 1927 Napoleon featured a climax with a triptych of images.) With the 2000 restoration, How the West Was Won‘s original panoramic three-panel joint lines were removed. The more recent blu-ray of the film presents it in a standard letterbox version. A “smile box” version, which distorts the image into a curve, is a gimmicky simulation that attempts to recreate a semblance of what the Cinerama experience was like.

How the West Was Won is more than a movie about the winning of the West. It’s a movie about America and about the distinctly American process of Cinerama. We are showing this film at a time when America is in a state of losing its identity. What had once been historical feats defined by heroism– characters in the film are identified by their achievements in the advertising– have now been given new interpretations by our society based on imperialism and the White Man’s expansion into native lands. These re-definitions aside, this is a film clearly in the framework of heroic endeavor. It’s about those who were laying tracks, forging new trails, and risking one’s own life in an unsettled land. How the West Was Won celebrates heroism, but it’s a balanced portrait nonetheless that shows the disillusionment of war and of a people. It projects a sympathetic portrait of American Indians that, although not intimate in nature, at least transcends the Western cliches. (Real Arapaho Indians were cast in the film.)

How the West Was Won is grand storytelling. It was designed to lure people away from television sets which, by the early 1960s, had severely affected movie attendance. Seventy years later, in an attempt to get people away from “streaming” services, we are presenting a film that can only be experienced on a big screen. On any other device for viewing, people will focus on the story, whereas it’s the visuals that make the film so lasting. The final train crash is one of the most spectacular finales you will see because it’s an actual train that is crashed– not a model. In fact, one stuntman lost a leg in filming it and nearly died, so it’s an impressive piece of film-making that warrants our full attention.

The Pickwick Theatre doesn’t have a curved screen or a three-projector system. Or even film reels, for that matter. But that doesn’t mean we can’t be swept up in the communal experience. Stay in the moment and allow yourself to become immersed in the film, to a degree that audiences were who experienced Cinerama in ’62. (In those early premiere engagements, theatres didn’t even sell popcorn; it was a real dress-up event!) We won’t go to that extreme, but be taken in with the full frame in front of you and the beauty of the land depicted. How the West Was Won offers a magnificent panorama of the American experience, and it is surely one of the most impressive films we’ve projected on the MEGA-screen.

~MCH

This diagram illustrates the Cinerama experience of the early 1960s.

A rare production photo of John Ford (second from left) directing Carroll Baker, on location near Paducah, Kentucky.